History of Ancient Philosophy

PHI 328. Syllabus. Welcome to the Course!

The dates that mark the beginning and end of Ancient philosophy are

conventional. In 585 BCE, a solar eclipse occurred that Thales of Miletus

predicted. In 529 CE, to protect the Empire from corruption, the Christian

Emperor Justinian prohibited pagans from teaching.

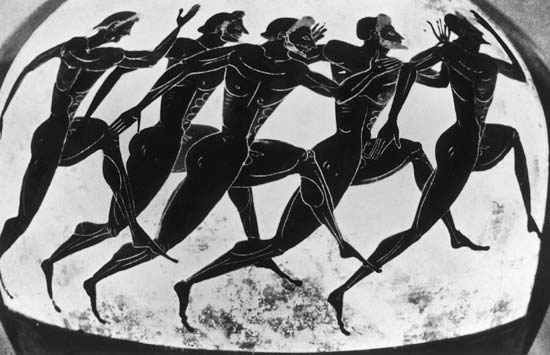

Terracotta Panathenaic prize amphora.

It is attributed to the Euphiletos Painter and dated to about 530 BCE. The image is on what The Met calls side 1 of the amphora.

A "stadion"

(στάδιον)

is 600 Greek feet and the distance of a footrace. The most famous was on a track in the

sanctuary of Olympia where the Olympic Games were held

(Pausanias, Description of Greece 5.8.1).

The word for the race came to name the track and the seats for spectators.

We see this in the history of the English word stadium.

The Panathenaic amphorae contained olive oil and were given to victors in

the Panathenaic Games.

The oil was from a sacred grove of olive trees in the Academy,

a place

Socrates frequented

and where Plato founded his school (Plato, Lysis 203a).

The grove was in an area of land about a mile northwest of Athens

(Pausanias,

Description of Greece 1.29). The Academy

took its name from Academus, who was the

object of cult worship

(Plutarch, Theseus 32;

Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Philosophers III.7).

The adjective

ἀκαδημικός

means

"of the Academy, Academic." The word academic comes from this adjective.

The noun cult is from the Latin

cultus ("a laboring at, caring for, cultivation").

Religion in Athens consisted in cults focused on the gods (Cicero,

On the Nature of the Gods II.8).

In a siege of Athens in 87-86 BCE, the Roman general Sulla "laid hands upon

the sacred groves, and ravaged the Academy, which was the most wooded of the

city's suburbs, as well as the Lyceum"

(Plutarch, Sulla 12).

The Lyceum

was the site of the school Aristotle founded.

Like the Academy, it was an area outside the city walls

that had become a place for intellectual discussion.

The Panathenaea

(the Greater and the Lesser) were festivals the

Athenians hosted in honor of the goddess Athena. They celebrated the Greater Panathenaea

every four years, in the third year of the Olympiad. (They

thought of it as a

πεντετηρίς

(a festival celebrated "every five years") because they counted inclusively:

"Festival . 2 . 3 . 4 . Festival.")

"Cimon was the first to beautify Athens with the so-called liberal

(ἐλευθερίοις = "fit for a free man")

and elegant resorts which were so excessively popular a little later [in the

time of Plato and Aristotle], by planting the market-place with

plane trees [Old World sycamores], and by converting

the Academy from a waterless and arid spot into a well watered grove, which he

provided with clear running-tracks and shady walks"

(Plutarch,

Cimon 13.8).

The adjective ἐλευθέριος translates into Latin as

liberalis.

"The first plane-trees that were spoken of in terms of high admiration were

those which adorned the walks of the Academy"

(Pliny the Elder,

Natural History XII.5).

Cimon (6th to 5th century BCE) was an Athenian

στρατηγός.

He was

involved in the rebuilding of Athens after the Persians destroyed it

in 480 BCE in the war between the Greeks and the Achaemenid Empire.

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BCE), toward the end of his

life, wrote a series of works to present the philosophy of the schools in his native

Latin. These works are an important source for the Hellenistic philosophers, as

almost nothing of their writings themselves have survived.

Pliny the Elder (1st century CE) was a Roman naturalist.

He died in the pyroclastic surge in

the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE

(Pliny

the Younger,

Letters VI.16).

Pliny the Younger (1st to

2nd century CE) was a Roman Lawyer and Imperial Magistrate under the Emperor Trajan.

In a letter to Trajan (Roman emperor 98-117 CE), Pliny the Younger

reports his encounter with Christians and asks how he should deal with their refusal

to participate in the imperial cult that gave Trajan divine status (Letters X.96).

Plutarch, Platonist, 1st to 2nd century CE.

Pausanias, traveler and geographer, 2nd century CE.

Diogenes Laertius, biographer, 3rd century CE.

He is the primary

source for our knowledge of Epicurus.

ἀμφορεύς,

ἀμφορεύς,

amphoreus, noun, "two-handled jar with a narrow neck."

ἀμφί ("on both sides")

+

φορεύς ("carrier"))

Vincent van Gogh, Large Plane Trees, 1889.

Theophrasus (371-287 BCE, head of the Lyceum after Aristotle) reports that one plane tree in the Lyceum

sent out roots a distance of 33 πήχεις (On Plants 1.7.1).

A πῆχυς is the length of a Greek forearm, point of the elbow to end of the middle finger.

Ancient philosophy is the traditional name for the

philosophical discussion that took place in the Greek

and Roman world in the period from 585 BCE to 529 CE.

Course Description

The history of Ancient philosophy is a subdiscipline of the history of philosophy.

The history of philosophy does not aim to solve philosophical problems. It tries to understand why philosophy came to exist and changed over time in the ways it did.

Because this is an enormous task, courses in the history of philosophy almost always have a focus. Our focus is the period from the beginning of Ancient philosophy in 585 BCE to the end of the Period of Schools in 100 BCE. This is the time of Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, and the Hellenistic philosophers (Epicurus, the early Stoics, and the Academics).

When we are thinking about the philosophical discussion that took place, we will see that the world appears differently to us than it did to the Ancient philosophers. They did not have our knowledge of science and technology. Their culture was different from ours.

This guarantees that many of their beliefs are going to appear false to us, but the principal question they tried to answer is one we still ask. They wanted to understand the human condition. They tried to identify the obstacles it poses for living the best life a human being can live, and they tried to understand how these obstacles might be overcome.

Our goal is to explain why they believed what they did. We want to get inside their minds so we can see why they thought certain propositions were plausible and others were not.

Course Assignments

Your grade for the course (A+, A, A-, B+, B, B-, C+, C, D, E) is a function of your grades on 5 quizzes (50% of the total grade), 10 prompts (40%), and 5 debriefing sessions (10%).

For each of the five modules (Presocratics, Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Hellenistic Philosophers), there is a quiz. Each quiz consists of ten multiple-choice questions. They test for knowledge of basic facts I set out in the lecture notes. The quizzes are not timed. You have two attempts.

For each of the five modules, there is a set of prompts. A good answer to a prompt is typically about a page in length. For each prompt, the grade for your answer is pass or fail.

For each of the modules, there is a debriefing session, These sessions provide you with the opportunity to share with the class your thoughts about the reading in the module.

The grades for the 5 quizzes (10 points each), 10 prompts (4 points each), and 5 debriefing sessions (2 points each) determine the grade for the course: A+ (100-97), A (96-94), A- (93-90), B+ (89-87), B (86-84), B- (83-80), C+ (79-77), C (76-70), D (69-60), E (59-0).

I do not accept late work unless the student provides a good reason. If you are going to submit work late, I accept more reasons as good reasons if you contact me before the due date.

I give incompletes only to accommodate serious illnesses and family emergencies.

I work with students on independent projects and on Honors Enrichment Contracts.

Textbook and Readings

There is no textbook. For the purposes of the course, you can easily get the information you need from the lecture notes. If you want a textbook, Ancient Greek Philosophy: From the Presocratics to the Hellenistic Philosophers is one I wrote and used for this course in the past.

The readings (linked through the lecture notes) are translations of some of the surviving texts.

These texts are the primary evidence we use to understand what the Ancient philosophers thought and why they had these thoughts. We attribute certain thoughts to them, and we try to show that they had these thoughts given what they wrote or others wrote about them.

Course Lecture Notes and Videos

The lecture notes for the course extend and sometimes correct the textbook I wrote.

This textbook is fixed in time. The lecture notes are not. They are works in progress. This is one of the great advantages of the open source publishing model. It is possible to correct mistakes as they are discovered and release new material as it becomes available.

The lecture notes are explanations of the texts, but they are also part of my effort to make Ancient philosophy more accessible. I host the notes on a server I rent from DigitalOcean.

I use Tufte CSS to style the lecture notes and this syllabus. In this style, the center column functions as a page in a book. The right column contains margin notes. Links are underlined, match the text in color, and do not change color on mouseover or when clicked.

In addition to the lecture notes, there are videos. In the videos, I present the material in a more conversational style and show how to use some online resources for Ancient philosophy.

The lecture notes and videos contain a lot of information. You do not need to understand all of it. The focus in the quizzes and prompts is on basic facts about Ancient philosophy.

I host periodic zoom group sessions and meet individually with students by zoom.

Contact Information

Thomas A. Blackson,

Philosophy Faculty

School of Historical, Philosophical, and Religious

Studies

Lattie F. Coor Hall, room 3356

PO Box 874302

Arizona State University

Tempe, AZ. 85287-4302

Email: blackson@asu.edu

Academic Webpage: tomblackson.com

History Webpage: history-of-ancient-philosophy.com