Free Will in Ancient Thought

Frede. Chapter Four: "Later Platonist and Peripatetic Contributions," 37-45

*** These lecture notes are works in progress ***

LECTURE NOTES 4

This chapter, like the previous one, is dense. Here are the main points.

The Main Points of the Chapter

• Platonists and Aristotelians develop their own notion of the will. They combine the view that the soul is tripartite with the view that every action requires the assent of reason.

• On this version of the tripartite theory, unlike Plato and Aristotle's versions, some impulsive impressions have the source of their impulsiveness in the nonrational parts of the soul.

• The Platonists and Aristotelians need an explanation for why reason assents to these impulsive impressions. Their explanation is that reason rationalizes these impressions.

Frede's Lecture (37-45)

1. By the second century A.D. Aristotelianism and Platonism had begun to eclipse

Stoicism, and by the end of the third century Stoicism no longer had any

followers. All philosophers now opted for some form of Platonism, as a rule a

Platonism which tried to integrate large amounts of Aristotelian doctrine,

including Aristotle's ethical principles. Hence the notion of the will

Aristotle's followers were called Περιπατητικοί (Peripatētikoi) because he

discussed philosophy while he was walking and his students were following him

in the

περίπατος

or "covered walk" of the Lyceum.

The Lyceum (Λύκειον)

was the site of Aristotle's school.

"[T]he associates of Aristotle were called the Peripatetics because they used to debate while walking in the Lyceum

(Cicero,

Academica I.4.17).

Peripateticus

(Latin translation of

Περιπατητικός),

"a disciple of the Peripatetic (or Aristotelian) school."

might have easily disappeared from the history of philosophy if Platonists and

Peripatetics [Aristotelians] had not developed their own such notion. This

involved retaining the idea that the soul is bi- or tripartite but also taking

the crucial step, not envisioned by Plato or Aristotle, that everything we do

of our own accord (hekontes) presupposes the assent of reason. Now

the word hekōn has indeed come to mean voluntary or willing.

Plato died in 347 BCE. Aristotle died in 322 BCE. In about 300 BCE, Stoicism begins with Zeno of Citium. By end the 3rd century CE, Stoicism had no defenders.

"All philosophers now opted for some form of Platonism."

Since the notion of will is Stoic in origin, it "might have easily disappeared from the history of philosophy if Platonists and Peripatetics had not developed their own such notion."

The Platonists and Aristotelians developed their notion by combining two ideas. They

combined their "bi- or

tripartite" theory of soul with the Stoic idea that

ἑκόντες, hekontes, adjective, plural form of ἑκών

ἑκών,

hekōn, adjective, "of own's own accord"

"everything we do of our own accord (hekontes) presupposes the assent of reason."

This gives the Platonists and Aristotelians a version of the tripartite theory of the soul that different from the versions in Plato and Aristotle.

Plato and Aristotle did not believe that "everything we do ἑκόντες presupposes the assent of reason." They thought that sometimes we act on nonrational desires (the desires in the nonrational parts of the soul) and that this does not involve reason.

2. This change was greatly facilitated by certain remarks in Aristotle and

particularly in Plato. We have a tendency, or at least for a very long time

have had a tendency, to understand Plato and Aristotle as if they claimed that

it were the task of reason to provide us with the right beliefs or, better

still, knowledge and understanding, while the task of the nonrational part of

the soul is to provide us with the desires to motivate us to act virtuously in

light of the knowledge and understanding provided by reason. But we have

already seen that this is not the view of Plato and Aristotle. According to

them, it is not the task of reason to provide us only with the appropriate

knowledge and understanding; it is also its task to provide us with the

appropriate desires. To act virtuously is to act from choice, and to act from

choice is to act on a desire of reason. The cognitive and the desiderative or conative aspects of reason are so intimately linked that we may wonder whether

in fact we should distinguish,

"conative"

From the Latin verb

conor

("to undertake, endeavor, attempt, try")

as I did earlier, between the belief of reason

that it is a good thing to act in a certain way and the desire of reason which

this belief gives rise to, or whether, instead, we should not just say that we

are motivated by the belief that it is a good thing to act in this way,

recognizing this as a special kind of belief which can motivate us, just as

the Stoics think that desires are nothing but a special kind of belief.

The Platonists and Aristotelians misunderstood Plato and Aristotle. They wrongly took them to think that action requires the assent of reason. Frede says that this misunderstanding "was greatly facilitated by certain remarks in Aristotle and particularly in Plato."

Frede does not cite the "remarks," and I do not know what he has in mind.

Frede next talks about how we have a tendency to misunderstand Plato and Aristotle.

"I shall endeavour to prove first, that reason alone can never be a

motive to any action of the will; and secondly, that it can never

oppose passion in the direction of the will"

(David Hume,

A Treatise of Human Nature, T 2.3.3.1, SBN 413).

What does Hume mean by "the will"?

"Of all the immediate effects of pain and pleasure, there is none more remarkable than

the will; and tho', properly speaking, it be not comprehended among the passions, yet

as the full understanding of its nature and properties, is necessary to the explanation

of them, we shall here make it the subject of our enquiry. I desire it may be observ'd,

that by the will, I mean nothing but the internal

impression we feel and are conscious of, when we knowingly give rise to any new motion

of our body, or new perception of our mind. This impression, like the preceding

ones of pride and humility, love and hatred, 'tis impossible to define, and needless to

describe any farther; for which reason we shall cut off all those definitions and

distinctions, with which philosophers are wont to perplex rather than clear up this

question; and entering at first upon the subject, shall examine that long disputed

question concerning liberty and necessity; which occurs so naturally in

treating of the will"

(A Treatise of Human Nature, T 2.3.1.2, SBN 399).

What is the misunderstanding?

It seems to be that reason provides beliefs and that the other parts of the soul provide desires.

How does this make it easy to think that every action requires the assent of reason?

I am not sure.

3. Further, the modern scholarly view, that according to Plato and Aristotle, reason provides the beliefs and the nonrational part of the soul provides the motivating desires, is grossly inadequate in that it overlooks their view that, just as reason has a desiderative aspect, so the nonrational part of the soul and its desires have a cognitive aspect. This should not be surprising, given that the nonrational part of the soul is supposed to be a close analogue of the kind of soul animals have. Animals have cognition. Indeed, Aristotle is willing to attribute to animals such enormous powers of cognition that some of them, according to him, can display good sense and foresight. Hence we naturally wonder why Aristotle denies reason to animals. The answer is that he, like Plato, has a highly restrictive notion of reason and knowledge, a notion which involves understanding why what one believes one knows is, and cannot but be, the way it is. Reason is the ability in virtue of which we have such knowledge and understanding. It is this kind of understanding which animals are lacking. Obviously, this leaves a lot of conceptual space for less elevated cognitive states which a nonrational soul, and hence an animal, is capable of.

"[T]he nonrational part of the soul and its desires have a cognitive aspect."

What does this mean? Frede's explanation follows.

4. We shall understand this better if we take into account that Plato and Aristotle distinguish three forms of desire, corresponding to the three different parts of the soul, and also, at least sometimes, seem to assume that each of these forms of desire has a natural range of objects which it naturally latches on to. Appetite aims at pleasant things, which give bodily satisfaction; spirit (thymos) aims at honorable things; and reason aims at good things. θυμός, thymos, noun, "strong feeling or passion" Since both Plato and Aristotle, unlike the Stoics, assume that pleasure and honor are genuine goods, reason can also aim at them, insofar as they are goods. The assumption seems to be that the appetitive part of the soul, though nonrational, can discriminate between the pleasant and the unpleasant. This, presumably, is supposed to serve a purpose. By and large an organism which is not spoiled or corrupted will perceive wholesome food or drink as pleasant, and unhealthy food and drink as unpleasant. So the ability to discriminate between the pleasant and the unpleasant will help the organism to sustain itself, if it is not corrupted in its tastes. When we see a delicious piece of cake, it will be appetite which has the impression that it would be very pleasant to have this piece of cake. Since appetite lacks reason, it has no critical distance from its impression. For it to have this impression amounts to the same as its having this belief. Similarly, the spirited part (thymos), being sensitive to what is honorable, will have the impression that it would be shameful to have yet another piece of cake.

There is a lot going on here.

In the tripartite theory in Plato and Aristotle, "[a]ppetite aims at pleasant things, which give bodily satisfaction; spirit (thymos) aims at honorable things; and reason aims at good things."

What does this mean?

Reason, for Aristotle, gives us the power to make choices for the sake of bringing about things we take to be good. These choices are desires we generate in deliberation.

How appetite and spirit "aim" is a little less clear.

Appetite does not calculate. It "lacks reason," and because it lacks reason, it "has no critical distance from its impression." In explanation, Frede says that for appetite "to have this impression amounts to the same as its having this belief."

We can begin to understand what Frede means if we think about an example.

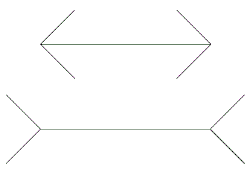

The Müller-Lyer Illusion.

The second horizontal line appears longer than

than the first, but in fact the two lines are the same in length.

"[T]hings about which we have at the same time a true belief may have a false

appearance; for instance the sun appears to measure a foot across, but we are

convinced that it is greater than the inhabited globe..."

(Aristotle,

On the Soul III.428b).

The example is from the Republic. Socrates says that sometimes although

reason "has measured and declares that certain things are larger or that some

are smaller than the others or equal, the opposite appears (φαίνεται) to it at

the same time"

(Republic X.602e).

Suppose two lines are arranged as in the Müller-Lyer illusion so that although it appears to our eyes that one is longer than the other, measurement reveals they are equal in length. Because we have measured the lines, we know that they are equal in length. This, though, does not eliminate the appearance that the lines are unequal in length.

This example begins to show what it might be for appetite to have "no critical distance from its impression." We would believe that the lines are unequal in length if we did not measure them, and the argument we construct for ourselves by measuring the lines does not stop us from continuing to have the appearance that they are not equal in length.

Just as the appetite can have impressions about the lengths of lines, it can have impressions about the pleasantness of things. These impressions can guide our behavior.

"When we see a delicious piece of cake, it will be appetite which has the impression that it would be very pleasant to have this piece of cake."

Appetite and reason, then, both can move us but they do this moving in different way.

Appetite does not have beliefs about what is good and what is bad. It has impressions of pleasantness. Appetite does not calculate. Calculation is a kind of reasoning, and appetite is incapable of reasoning. Appetite, however, can do something like calculation and, as a result, make us desire to do something to get the thing (the cake we see on the table) that has given us the impression that doing something (eating the cake) would be pleasant.

5.

"If a living thing has the capacity for perception, it has the capacity for

desire. For desire (ὄρεξις) comprises appetite (ἐπιθυμία), spirit (θυμὸς), and

wish (βούλησις). All animals have at least one of the senses, touch. Where

there is perception, there is pleasure and pain ..., and where there are

these, there is appetite: for this is desire for what is pleasant"

(Aristotle,

On the Soul II.3.414b1).

ἀκρασία,

akrasia, noun, alternate spelling of

ἀκράτεια,

akrateia, "want of power, incontinence,"

φαντασία,

phantasia, noun, "appearing, appearance"

We should also remember that Aristotle explains nonrational desire as

originating in the fact that animals not only can perceive things but also

perceive them as pleasant or unpleasant. So if you perceive the kind of thing

you have experienced as pleasant, without the intervention of reason you have

the agreeable impression that there is something pleasant within reach,

something which you expect to give you pleasure if you get hold of it. This is

an impression and an expectation produced by the nonrational part of the soul.

In his remarks on impetuous akrasia—cases in which the spirited part

of the soul, for instance, in its anger, rashly preempts the deliberation of

reason—Aristotle says that those who are prone to this kind of condition do

not wait for reason to come to a conclusion but tend to follow their

phantasia, that is, their impression or disposition to form

impressions, rather than their reason (EN 7, 1150b19–28).

EN = Ethica Nicomachea =

Nicomachean Ethics

"[T]he impetuous are led by passion because they do not stop to deliberate....

It is the quick and the excitable who are most liable to the impetuous form of incontinence,

because the former are too hasty and the latter too vehement to wait for reason,

being prone to follow their appearance (φαντασίᾳ)"

(Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics VII.1050b).

So the akratic sort of person follows an impression formed by or in the

spirited part of the soul rather than reason.

"Aristotle explains nonrational desire as originating in the fact that animals not only can perceive things but also perceive them as pleasant or unpleasant."

What does it mean to perceive something "as pleasant"?

I am not sure.

Maybe it is to "perceive the kind of thing you have experienced as pleasant."

In this case, there are two states. There is the perception of a particular piece of cake, and there is the "expectation" [the Greek word would be δόξα] that eating cake results in pleasure.

Somehow these together can give you an "agreeable impression that there is something pleasant within reach, something which you expect to give you pleasure if you get hold of it."

Does Aristotle talk about "agreeable impressions"?

Frede does not cite any passages.

6. Later Peripatetics and Platonists, then, were following Plato and Aristotle

in thinking that a nonrational desire consisted of a certain kind of agreeable

or disagreeable impression, with its origin in a nonrational part of the soul.

They could preserve the division of the soul by supposing that different kinds

of impulsive impressions have their origin in different parts of the soul,

rather than in reason or the mind, as the Stoics had assumed. But they could

now agree with the Stoics (though this in fact meant a significant departure

from Plato and Aristotle) that any impression, however tempting it may be,

needs an assent of reason to turn it into an impulse that can move us to

action. So now reason does appear in two roles. It has or forms its own view

as to what would be a good thing to do, and it judges whether to assent or

refuse to assent to the impulsive impressions which present themselves. Thus

we get the division of reason or the intellect into two parts, as we find in

later traditions,

Thomas Aquinas, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Now the intellect assents to something in two ways. One way, because it is moved to assent

by the object itself, which is known either through itself (as in the case of first principles,

of which there is understanding), or through something else already known (as in the case of

conclusions, of which there is knowledge). In another way, the intellect assents to something,

not because it is sufficiently moved to this assent by its proper object, but through a certain

voluntary choice (electionem voluntarie) turning toward one side rather than the other. And if this is done with

doubt or fear of the opposite side, there will be opinion; if, on the other hand, this is done with

certainty and without such fear, there will be faith"

(Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica II-II, question 1, article 4).

for instance, in Thomas Aquinas: a cognitive part and the will.

Think again about the cake example.

The impression in the appetite is that this piece of cake will give you pleasure if you eat it. This impression is agreeable, and you will act on it if appetite is in control.

How does this work in the the tripartite theory in the "[l]ater Peripatetics and Platonists?"

The "[l]ater Peripatetics and Platonists" think that such impressions are impulsive impressions, and they understand impulsive impressions to require the assent of reason to result in impulses. This commits them to thinking that if someone acts on this impression (and thus tries to get the cake and eat it), reason in his soul has assented to this impulsive impression.

"[N]ow reason does appear in two roles."

What are the two roles?

"[Reason] has or forms its own view as to what would be a good thing to do, and it judges whether to assent or refuse to assent to the impulsive impressions which present themselves."

The first role ("...[i]t has or forms...") is as the "cognitive part." Reason forms beliefs "as to what would be a good thing to do."

The second role ("...it judges ... impulsive impressions...") is as the "will."

Reason = the cognitive part + the will.

7. Another factor which could facilitate this move, as I indicated earlier, is that assent could be construed rather generously as involving simple acceptance of, or acquiescence to, an impression, ceding to it, giving in to it, rather than an active, explicit act of assent. This is why many philosophers were now prepared to say that even nonhuman animals assent to their impressions in that they cede to them and rely on them in their action.

Since they thought that assent can be "acquiescence," the Platonists and Aristotelians found it easy to think that every action stems from the assent of reason.

8. There is an important development in the first century B.C. which further

facilitated this change. It is usually claimed that the Stoic Posidonius early

in the first century B.C. criticized Chrysippus's doctrine that the passions

of the soul have their origin in reason and that he reverted to a tripartite

division of the soul. The evidence for this comes from

Galen of Pergamum (130-210 CE), Greek physician and philosopher.

De Placitis Hippocratis et Platonis

=

On the Doctrines of Hippocrates and Plato.

Galen wrote the first six (of the nine) books of On the Doctrines of

Hippocrates and Plato in the period from 162 to 166 CE. His aim is to

show that Hippocrates and Plato agreed and were correct about the faculties

of animals. The work is largely polemical. In books III-V, he attacks

Chrysippus' understanding of the soul and the passions.

Galen, in particular, Galen's De Placitis Hippocratis et Platonis,

but it has to be treated with great caution. Galen is an extremely polemical

author who shows few scruples in defending or advancing a good cause. He is

firmly set against Stoicism and eager to show that on a matter dear to him,

such as the division of the soul, the great authority of the school,

Chrysippus, who denies this doctrine, has been contradicted by another major

Stoic, Posidonius. Hence I have great sympathy with John Cooper's attempt to

show that Galen was simply wrong to interpret Posidonius as having thought

that there is an irrational part of the soul. On the other hand, it is obvious

that Posidonius did criticize Chrysippus and must have said things which

allowed Galen to interpret him in this way. What was at issue between

Chrysippus and Posidonius?

This "important development" is not straightforward to understand.

What are the "passions"?

A "passion" (πάθος) is an "excessive impulse" (ὁρμὴ πλεονάζουσα). The early Stoic view is that excessive impulses stem from false beliefs about what is good and what is bad.

Posidonius of Apameia 2nd to 1st century BCE), a Stoic polymath whose writings have survived only in fragments.

Galen says that the Posidonius criticized Chrysippus and the traditional Stoic view of the soul.

"[I]t is not surprising that he [Chrysippus, an early Stoic] was perplexed about the origin of

vice [false beliefs about what is good and what is bad]. He could not state its cause

or the ways in which it comes to exist; and he could not discover how

it is that children err. On all these points it was reasonable, I [Galen] think, for

Posidonius [a middle Stoic] to censure and refute him [Chrysippus]. For if from the start children felt a

kinship with virtue, their misconduct could not arise

internally or from themselves, but necessarily come to them only from the

outside. But even though they are brought up in good habits and are given the

education they ought to have, yet they are invariably observed doing

something wrong; and Chrysippus acknowledges this fact. ... [H]e granted that

even if children were raised under the exclusive care of a philosopher and

never saw or heard any example of vice, nevertheless they would not

necessarily become philosophers. There are two causes of their

corruption; one arises in them from the conversation of the majority of men,

the other from the very nature of things (αὐτῆς τῶν πραγμάτων τῆς φύσεως).

"When a rational being is perverted, this is due to the

persuasiveness of external pursuits (τὰς τῶν ἔξωθεν πραγματειῶν πιθανότητας) or sometimes

to the influence of associates"

(Diogenes Laertius,

Lives of the Philosophers VII.

1.89).

"If it is the persuasion of things (πραγμάτων πιθανότητες), by which some things appear to be good,

when they are not good, let us seek a remedy for this"

(Epictetus, Discourses I.27).

πραγματεία

πρᾶγμα

I have objections to both of these causes, beginning with that which arises from

associations. It occurs to me to wonder why it is that when they have seen and

heard an example of vice, they do not hate it and flee from it, since they feel no

kinship with it; and I wonder all the more that they should be corrupted when

they neither seen nor hear such examples and are deceived by the very things (πραγμάτων)

themselves. What necessity is there that children be enticed by pleasure as a

good, when they feel no kinship with it, or that they avoid and flee

from pain if they are not by nature also alienated from it? ...

[W]hen he [Chrysippus] says that corruption

arises in inferior men in regard to good and bad because of the

persuasiveness of impressions (πιθανότητα τῶν φαντασιῶν) and the talk of men,

we must ask him why it is that pleasure projects the persuasive impression

that it is good, and pain that it is bad"

(On the Doctrines of Hippocrates and Plato V.5.9).

This passage is confusing.

The issue is about the Stoic explanation of "origin of vice." The Stoic view is that is that vice consists in false beliefs about what is good and what is bad. It is the Stoic view too that we all get these beliefs as we acquire reason and thus become adults.

Galen attributes a view to Chrysippus about the origin of these false beliefs. According to the view Galen attributes to Chrysippus, there are two "causes" of vice.

1. One of these causes is easier to understand than the other.

The easier to understand cause is "the conversation of the majority of men." We are supposed to get the false beliefs that constitute vice from the society in which we live.

About this cause of vice, Galen seems to say that Chrysippus admits that "even if children were raised under the exclusive care of a philosopher and never saw or heard any example of vice, nevertheless they would not necessarily become philosophers."

"[Although we become] foolish, vicious, and enslaved, we never

were actually wise, virtuous, and free"

(97).

No one begins life as wise because no one has reason when he is born.

Everyone acquires reason as he becomes an adult. As he acquires reson,

he becomes a fool. Nature does

not make fools. Instead, we become fools because we are

rash in our assent and thereby enslave ourselves.

Why are we rash in our assent when we acquire reason?

Here is Frede's answer:

“[T]he grownup, the animal soul having disappeared, does not have any

instinctive impulses…. The only way for him to be moved is by assent to

impulsive impressions. But impulsive impressions presuppose an evaluation

of the objects of our impulses. And at this point ordinary human beings in

ordinary human societies can hardly fail to make the mistake which even

philosophers like the Platonists and the Peripatetics make. They think

that since nature from birth has endowed us with certain natural

inclinations and disinclinations the objects of these natural impulses

must be goods and evils. Hence their behavior comes to be motivated, not

by instinctive impulses, but by affections of the soul, namely their

assent to impulsive impressions in which the objects of the natural

inclinations with which we are born are represented as good or bad”

(Michael Frede,

"The Stoic Doctrine of the Affections of the Soul," 109.

The Norms of Nature (edited by Malcolm Schofield and Gisela

Striker), 93-110. Cambridge University Press, 1986).

The Stoics think, as Frede understands them, that because we believe that

"nature from birth has endowed us with certain natural

inclinations and disinclinations," we rashly assent to the impression

that "the objects of these natural impulses

must be goods and evils."

Why

do we do this?

The

premise is the truth that nature has endowed us with these impulses.

The conclusion is that the falsity that the objects of the impulses are "goods and evils."

This conclusion is not a logical consequence of the premise.

2. The harder to understand of the two causes is "the very nature of things."

Galen later restates this second cause as "the persuasiveness of impressions."

He also explains what is supposed to happen. He says "that pleasure projects (προσβάλλουσι) [or strikes us with] the persuasive impression that it is good, and pain that it is bad."

What does this mean?

I am not sure.

How does the second cause relate to "the conversation of the majority of men."

Are we supposed to think that once we have some false beliefs from society, "the persuasiveness of impressions" can give us others? Or are we supposed to think that even if we did not get false beliefs from those who raise us (say, because we are raised by philosophers), we would get them from "the persuasiveness of impressions"?

I do not know the answer.

9. From the information we have about Chrysippus and the earlier Stoics, we get the impression that human beings in the course of their natural development would turn into virtuous and wise human beings, if only this development were not interfered with from the outside through corruption from those who raise us and by the society we grow up in. As it is, though, we are made to believe that all sorts of things are good and evil which in fact are neither, and so we develop corresponding irrational desires for or against these things which are entirely inappropriate but which come to guide our life.

What is the "course of ... natural development" for human beings?

Part of this "natural development" is the development of reason. The Stoic view is that reason is not inborn but that it develops in human beings as they mature from children into adults.

"[W]e get the impression that [Chrysippus and the earlier Stoics thought that] human beings in the course of their natural development would turn into virtuous and wise human beings, if only this development were not interfered with from the outside through corruption from those who raise us and by the society we grow up in."

This is puzzling.

Galen, as we just saw, says that Chrysippus cites two causes for the "origin of vice."

The explanation is puzzling too.

If the false beliefs come from society, the false beliefs come from individuals in the society. Now a regress threatens. Maybe, though, the Stoic idea is that there have always been human beings living in societies. So the individuals who have false beliefs got them from the society in which they were raised. This society contained individuals who got their false beliefs from the society in which they were raised, and so on back forever in time.

10. I take it that Posidonius questioned this picture. "The first men and those who sprang from them, still unspoiled, followed nature, having one man as both their leader and their law, entrusting themselves to the control of one better than themselves. ... Accordingly,in that age which is maintained to be the golden age, Posidonius holds that the government was under the jurisdiction of the wise" (Seneca (a late Stoic), Epistles XC). He had an interest in the history of mankind, and he seems to have assumed that there was an idyllic original state of innocence in which people lived peacefully together without coercion, freely following those who were wise. But this original paradisiacal state was lost through corruption, greed, envy, and ambition. Now, this corruption cannot have come from the outside, from society, as society was not yet corrupt. It must have come from the inside, then. If we look for the weak spot on the inside, it must lie in the misguided but tempting impulsive impressions which we find hard to resist. Take, for instance, the case in which one wants to run away because one fears for one's life. For a Stoic this is an unreasonable, inappropriate, and misguided desire, because only evils are to be feared, and death is not an evil. According to the classic Stoic account, the source of this inappropriate desire is the belief that death is an evil. This is not a belief we develop naturally. We acquire it from the outside, because we grow up in a society which believes that death is an evil. Given this belief, the impulsive impression that one might die from an infection takes on a very disturbing coloring and is difficult not to assent to.

What is this "picture" that Posidonius questioned?

Posidonius accepted that human beings have always lived in society and that at first

Why does Posidonius question this?

Frede does not say, but my guess is that he thinks that we are seeing the influence of something Plato says.

there were no false beliefs about what is good and what is bad.

What he questions is whether this state is sustainable.

So Posidonius, as Frede understands him, thinks that vice comes from the "inside."

Is the view that a cause of vice is "the persuasiveness of impressions"?

I am not sure.

Galen's explanation of what Posidonius thinks does not help much.

"[Posidonius tries to show that sometimes] false suppositions ... arise through the pull of affections (παθητικῆς), but that false opinions precede this pull, because the reasoning part has become weak in judgement. For impulse is sometimes generated in an animal as a result of judgement of the reasoning part, but often as a result of the movement of the affective part" (On the Doctrines of Hippocrates and PlatoV.5.21).

This explanation is pretty obscure.

11. Posidonius seems to have asked whether the coloring of the impression must be due to a belief of reason or whether, instead, it could have its origin in a nonrational part of the soul or even in the body and its constitution and state. It could be a natural, nonrational reaction of an organism which sees its life threatened. Similarly, it might be more plausible to refer the coloring of the impulsive impression, not to the mistaken belief that this piece of cake is something good but rather to the body of an organism which is depleted and craving some carbohydrates. It does not matter for our purposes whether Posidonius believed in a nonrational part of the soul. What matters is his suggestion that the impulsive character of at least some of our impressions does not originate in reason's beliefs and thus, ultimately, in some sense, outside us but seems to have its origin in us, for instance, in the particular constitution or state of our body which makes us crave certain things. Peripatetics and Platonists would have gladly taken such considerations as a confirmation of the view that nonrational desires are constituted by impressions which have their origin not in reason but in a nonrational part of the soul.

Posidonius suggests "that the impulsive character of at least some of our impressions does not originate in reason's beliefs [contrary to the traditional Stoic view] and thus, ultimately, in some sense, outside us but seems to have its origin in us, for instance, in the particular constitution or state of our body which makes us crave certain things."

If "the impulsive character of at least some of our impressions" is not a matter of reason, what accounts for the fact that these impressions are impulsive?

"[I]t might be more plausible to refer the coloring of the impulsive impression, not to the mistaken belief that this piece of cake is something good but rather to the body of an organism which is depleted and craving some carbohydrates."

This is confusing, but we don't have to worry about whether it is what Posidonius really thought. Frede is trying to explain how the Platonists and Aristotelians could think that some impulsive impressions are the desires in the nonrational parts of the soul. His explanation is that they could say to themselves that even a Stoic as influential within the school as Posidonius thought that the impulsiveness of some impressions is not a matter of reason.

12. The second, probably closely connected, development has to do with

Stoic analysis of the emotions. If we look, for instance, at Seneca's

treatise on anger,

Seneca (4 BCE - 65 CE), major Roman Stoic

Seneca,

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

we easily get confused, and commentators used to get confused. This is

because anger (ira)

ira, noun, "ire, anger"

ἀπάθεια,

apatheia, noun,

(ἀ "not" +

πάθος,

noun, páthos, "passion"), "without passion,"

The Platonic and Aristotelian ideal is

μετριοπάθεια.

"[The ruler in the just city] makes the least lament and bears it most mildly

when any such misfortune overtakes him"

(Republic III.387e).

πάθος, noun, páthos, "passion"

(Latin: perturbatio)

προπάθεια, propatheia, noun, "prepassion"

A προπάθεια is an impulsive impression based on a

false belief about what is good or what is bad. A πάθος is the

assent to such an impression.

and other terms for emotions, desires, or passions of the soul, are

systematically used ambiguously. In classical Stoic doctrine anger refers to

the desire or impulse one has which makes one act in anger because one has

assented to, accepted, and yielded to the relevant impulsive impression. But

Seneca also uses ira to refer to the mere impression. Later Stoics

clarified this ambiguous use of terms like anger or fear by distinguishing

between a propatheia, an incipient passion, which is the mere

impulsive impression not yet assented to, and a pathos, the passion

in full force, when the impulsive impression has received assent. This

distinction may very well go back to Posidonius. In any case, it would allow

Peripatetics and Platonists more easily to identify their nonrational

desires with the impulsive impressions they took to be generated by the

nonrational part of the soul. They could do this all the more readily since

for them, unlike the Stoics, having a desire in itself did not mean that one

acted on it. Otherwise they could not have assumed that there could be an

acute conflict of desires and that one could act in such a case by following

either reason or appetite.

These remarks, like his discussion of Posidonius, are part of Frede's explanation for how the Platonists and Aristotelians could "identify their nonrational desires with the impulsive impressions they took to be generated by the nonrational part of the soul."

How does the explanation work?

Seneca sometimes uses "anger" (and other terms for the emotions) for an impulsive impression to which assent has not been given. These impulsive impressions correspond to nonrational desires for the Peripatetics and Platonists.

13. I have so far talked only about what Platonists and Peripatetics would have had to do to get a notion of the will which preserved their assumption of a bi- or tripartite soul and how they could easily have done this, once they accepted the assumption that any action, any doing which we are not made to do by force, presupposes an act of assent. I have not yet done anything to show that this is what Platonists and Peripatetics actually did. Let us begin with assent.

Now Frede tries to show that the Platonists and Aristotelians did take over the Stoic notion of assent according to which all actions requires the assent of reason.

14. We find this Stoic notion taken over by Platonists in many texts. We know

from a fragment of

Numenius (2nd century CE)

Plotinus (204/5 – 270 CE)

Porphyry (3rd to 4th century CE),

φιλόλογος,

philologos, adjective, "lover of words, talkative"

φιλόσοφος, philosophos, adjective, "lover of wisdom"

"Numenius, when he says that the capacity for assent admits of activities,

says that the imaginative faculty is an accident of it – not

its function or purpose, but something that accompanies it. The Stoics not

only root perception in impression, but make its substance

dependent on assent: perceptual impression is assent, or the perception of

one’s impulse to assent. Longinus does not think that there is a capacity for

assent at all" (Porphyry, On the

Powers of the Soul. Stobaeus, Anthology 1.49.25;

349.19–28.

Fragment 45 in E. des Places, Numénius, Fragments).

"In the cases where we assent to our persuasive impression

on account of its persuasiveness, still not assenting was also

in our power, provided that the impression does

not drag us and manipulate us like puppets to itself"

(Porphyry, On What is in Our Power. Stobaeus, Anthology 2.8.40;

167.9-17.

269F in Smith, Porphyrii philosophi fragmenta).

Porphyry's On What is in Our Power survives in

the fragments Stobaeus preserved in his Anthology (2.8.39-42).

The work itself seems to be a commentary on

Plato's

myth of Er (Republic X.614b).

Porphyry's work On the Powers of the Soul (ap. Stob., Ecl.

I.349.19ff) that Longinus doubted whether there was such a thing as the soul's

power to give assent. But it seems that Longinus here, as in other respects,

was rather singular in his conservatism. I take it that he knew his Plato

extremely well and criticized what his fellow Platonists, like Numenius,

presented as Plato's philosophy. It was this, I assume, which earned Longinus

Plotinus's rebuke that he was a philologos, rather than a philosopher

(Porphyry, VP 14). At a time when Plato was about to become “the

divine Plato,” Longinus still had no difficulty constantly criticizing Plato's

style (see Proclus, in Tim. 1.14.7). Longinus was the only

significant Platonist of his time who held on to a unitarian rather than a

binitarian or trinitarian conception of God. And so we should not be surprised

that Longinus, quite rightly, doubted that Plato's philosophy had envisaged a

doctrine of assent. But Numenius, the most important Platonist before

Plotinus, adopted such a doctrine (see Stobaeus), as did, at least at times,

Plotinus and also Porphyry, the student of Longinus and Plotinus (see Porphyry

ap. Stob., Ecl. II.167.9ff)

Porphyry reports that "Longinus doubted whether there was such a thing as the soul's power to give assent." Frede takes Longinus, in this doubt, to criticize his fellow Platonists, such as Numenius (who believed that Plato himself thought all action requires the assent of reason).

There is a passage in Plato that talks about assent. Socrates is the speaker.

"Now, wouldn’t you consider assent and dissent, wanting to

have something and rejecting it, taking something and pushing it way, as all

being pairs of mutual opposites—whether of opposite doings or of opposite

undergoings does not matter?

Yes, they are opposites.

What about thirst, hunger, and the appetites as a whole, and

also willing and wishing? Would you include all of them somewhere among

the kinds of things we just mentioned? For example, wouldn’t you say that

the soul of someone who has an appetite wants the thing for which it has

an appetite, and draws toward itself what it wishes to have; and, in addition,

that insofar as his soul wills something to be given to it, it nods assent to

itself as if in answer to a question, and strives toward its attainment?

I would.

What about not-willing, not-wishing, and not-having an

appetite? Wouldn’t we include them among the very opposites, cases in

which the soul pushes and drives things away from itself?

Of course

(Republic IV.437b).

Here Socrates does not say assent is necessary for every action. So, in this passage, "reason is not made to appear in two roles, [as it does in the later Platonists,] first as presenting its own case and then as adjudicating the conflict by making a decision or choice" (lecture 2, 10).

If Plato "envisaged a doctrine of assent," he would think more than that reason in the soul sometimes assents. He would think that every action requires the assent of reason and thus that in the case of conflict between the parts of the soul, reason "appear[s] in two roles."

"Longinus was the only significant Platonist of his time who held on to a unitarian rather than a binitarian or trinitarian conception of God. And so we should not be surprised that Longinus, quite rightly, doubted that Plato's philosophy had envisaged a doctrine of assent."

I suspect there is an interesting story here, but I do not know what it is.

15. We also find this doctrine of assent in the Peripatetics. Thus, for

instance, Alexander of Aphrodisias

Alexander of Aphrodisias (2nd to 3rd century CE), Aristotelian philosopher

and commentator.

Alexander of Aphrodisias, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

De fato = On fate, written in about 198-209 CE.

From the On fate, we know

the Roman emperors Septimius Severus and Antoninus Caracalla

appointed Alexander to an endowed chair of

Aristotelian philosophy.

ἑκούσιος, hekousios, adjective, "of one's own accord."

ἑκούσιος is derived

from ἑκών and has the same

basic meaning. The only difference is that it is said of actions.

"It is agreed by everyone that man has this advantage from nature over the

other living creatures, that he does not follow appearances in the same way

as them, but has reason from her as a judge of the appearances that impinge

on him concerning certain things as deserving to be choosen. Using this, if,

when they are examined, the things that appeared are indeed as they initially

appear, he assents to the appearance and so goes in pursuit of them

(συγκατατίθεταί τε τῇ φαντασίᾳ καὶ οὕτως μέτεισιν αὐτά); but if they

appear different or something else appears more deserving to be choosen. he

chooses that, leaving behind what initially appeared to him as deserving choice"

(Alexander of Aphrodisias, De fato XI).

in the De fato (XI, p. 178, 17ff Bruns) explains that human beings,

unlike animals, do not just follow their impressions but have reason which

allows them to scrutinize their impressions in such a way that they will

proceed to act only if reason has given assent to an impression. A bit later

in the same text (XIV, p. 183, 27ff), Alexander distinguishes between what we

do of our own accord (hekousion) and what we do because it is up to

us (eph' hēmin). Obviously, he has in mind Aristotle's distinction

between what we do of our own accord (hekontes) and what we do by

choice. We remember that the latter class is restricted to actions we will and

choose to do, whereas the former also includes those actions which we do when

motivated by a nonrational desire. But Alexander now, unlike

Aristotle, characterizes this former class as involving a merely unforced

assent of reason to an impression, whereas the latter class is supposed to

involve an assent of reason based on a critical evaluation of the impression.

So it is clear that Alexander takes even an action done on impulse, for

instance, an akratic action, to involve the assent of reason to the

appropriate impression.

Frede cites Alexander of Aphrodisias to show the Aristotelians have the "doctrine of assent."

Alexander, according to Frede, "explains that human beings, unlike animals, do not just follow their impressions but have reason which allows them to scrutinize their impressions in such a way that they will proceed to act only if reason has given assent to an impression."

Frede discusses Alexander again in chapter 6.

16. Let us return to the Platonists. There are any number of passages which show that Platonists construe following a nonrational desire rather than reason in a similar way. Thus Plotinus (Enn. VI.8.2) raises the question of how we can be said to be free, if it would seem that the impression and desire pull us wherever they lead us. It is clear from the context that Plotinus is speaking about nonrational desires. And it is clear from the curious expression (hē te phantasia [ἥ τε φαντασία]...hē te orexis [ἥ τε ὄρεξις], with the subsequent verb forms in the singular) that he is identifying the nonrational desire with an impression.

"When impression (φαντασία) compels and desire (ὄρεξις) pulls us in whatever direction it leads, how are we given the mastery in these circumstances?" (Plotinus, Enneads VI.8.2).

17. Porphyry (ap. Stob., Ecl. II.167.9ff) tells us that somebody

whose natural inclinations lead him to act in a certain way could also act

otherwise since the impression does not force him to give assent to it.

Calcidius, in his commentary on the Timaeus,

Plato's Timaeus, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

adsensus is an alternative form of assensus

assensus,

noun, "assent"

voluntas,

noun, "will"

φαντασία,

phantasia, noun, "appearing, appearance"

which is taken to reflect a pre-Plotinian source, claims (in section 156) that

the soul is self-moved and that its motion consists in assent

(adsensus) or desire but that this presupposes an impression (or the

ability to form impressions) which the Greeks call phantasia.

Sometimes, though, he continues, this impression is deceptive, corrupts

assent, and brings it about that we choose the bad instead of the good. In

this case, Calcidius says, we act by being lured by the impression to act in

this way, rather than by voluntas. So Calcidius, just like Alexander

of Aphrodisias (De fato XIV, p. 183) and other Platonist and

Peripatetic authors, is preserving the distinction between willing

(boulêsis) to do something, in Plato's and Aristotle's narrow sense,

and giving assent in such away that one can be said to do something willingly

in a wider sense, simply because one has assented to it.

In about 321 CE, Calcidius (4th century CE) translated part (to Stephanus number 53c) of Plato's Timaeus from Greek to Latin and provided an extensive commentary on the dialogue.

"Reason or deliberation is an inner movement of the ruling principle within the soul; and the latter is self-moving, its movement being assent or impulse. Assent and impulse, then, are self-moving, although not in the absence of imagination, which the Greeks call φαντασία. So it happens that the movement of the soul's ruling power, its consent, is very often depraved because of a deceptive image and chooses the bad over the good. There are many reasons for this: an uncultivated coarseness in deliberating, ignorance, a mind excessively devoted to importune adulation, the prejudice of false opinion, habituation to depravity--at all events, a certain tyrannical domination on the part of one or another vice, that being the reason for our being said to sin owing to compulsion or compulsive allurements rather than our will" (Calcidius, Commentary on Plato's Timaeus 156).

What is going on in this passage?

Calcidius seems to attribute to Plato the view that every action requires the assent of reason. Sometimes, though, reason does not give its assent "willingly." Instead, it is supposed to be somehow compelled by one of the causes Calcidius lists.

18. It is this wider notion of willing, that is, assenting to an impulsive

impression, whether following reason or going against reason, which gives

rise to the notion of the will as the ability and disposition to do things

by assenting to impressions, whether they have their origin in reason or in

the nonrational part of the soul and whether they are reasonable or

Aspasius (2nd century CE).

I do not know which passages in Aspasius Frede has in mind.

unreasonable. In this way we come to have a notion of a will in Platonist

and Peripatetic authors as, for instance, in Aspasius (Commentary on

Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics).

The Platonists and Peripatetics have a notion of a will.

According to this notion of a will, the will is "the ability and disposition to do things by assenting to impressions, whether they have their origin in reason or in the nonrational part of the soul and whether they are reasonable or unreasonable."

How does this notion differ from the one in Stoicism?

In Stoicism, the soul in the adult is reason. So, in Stoicism, reason does not play two roles.

19. Obviously, this change in the way of looking at nonrational desire has considerable consequences. It is one thing to think of human beings as sometimes being overwhelmed by a powerful desire for something or even to think that reason sometimes is overwhelmed by a powerful desire for something; we readily understand, or believe we understand, how this might happen. It is quite another thing to relocate this conflict as a conflict within reason or the mind. That refocuses our attention on thoughts or impressions. But what is so powerful about these impressions that reason may not be able to resist them?

The Platonist and Peripatetic notion of the will raises a question about reason.

Why would reason find it hard to resist assenting to nonrational impulsive impressions?

Frede first gives the Stoic explanation.

On the Stoic view, according to Frede, reason's own beliefs about what is good and what is bad make it difficult for reason to resist assenting to impulsive impressions.

20. Classical Stoicism has a relatively easy answer. If impressions have such a power over you, it is because they are formed by reason in a way which reflects your beliefs, and, given these beliefs, it is not surprising if you assent to these impressions. If you think that death is a terrible evil, it is not surprising that you cannot resist the thought to run as fast as you can, if you see death coming your way. It is your reason, your beliefs, which give your impressions their power. But if you do not think that these impressions have their origin in reason and that their power is due to your beliefs, it becomes rather difficult to understand how they would have such a power over reason that, even if they have little or nothing to recommend them rationally, reason can be brought to assent to them. At this point we have to beware of the danger of just covering up the problem by appealing to the free will, by claiming that this is precisely what it is to have a free will—to be able to give assent not only to impressions which with good reason we find acceptable but also to impressions which have no merit rationally. Instead I want to look briefly at some ancient attempts to explain the appealing or tempting character of impressions we wrongly give assent to. Needless to say, we are talking about temptations and about the origins of the very notion of a temptation.

What is the "relatively easy answer"?

It is the Stoic answer.

What answer is that?

"It is your reason, your beliefs, which give your impressions their power."

What does this mean?

Consider Frede's "death" example. You have (what according to the Stoics is) the false belief that your death is bad. You have the impression that "death [is] coming your way." Because of your belief that your death is bad, this impression is impulsive. If you assent to it, you have the excessive impulse "to run [away from death] as fast as you can."

Why does reason find it difficult to resist assenting to this impression?

Frede says that "[i]t is your reason, your beliefs, which give your impressions their power."

How do "your beliefs" do this?

Frede does not say. He only says that it is "not surprising" that it happens.

Here is a guess as to why it is "not surprising."

Sextus Empiricus is explaining Carneades's view of assent to persuasive impressions, but the examples

he presents seem to be ordinary ones.

"A man, for example, is being

pursued by enemies, and coming to a ditch he receives an impression

which suggests that there, too, enemies are lying in wait for him; then being carried away by this impression,

as a persuasive impression, he turns aside and avoids the ditch, being led by the persuasiveness of the impression,

before he has exactly ascertained whether or not there really is an ambush of the enemy at the spot"

(Sextus Empiricus, Against the Logicians I.185).

"For example,a on seeing a coil of rope in an unlighted room a man jumps over it,

conceiving it for the moment to be a snake, but turning back afterwards he inquires into the truth,

and on finding it motionless he is already inclined to think that it is not a snake, but as he reckons,

all the same, that snakes too are motionless at times when numbed by winter’s frost, he prods at the

coiled mass with a stick, and then, after thus testing the impression received, he assents to the fact

that it is false to suppose that the body presented to him is a snake"

(Sextus Empiricus, Against the Logicians I.187).

If we spend a lot of time

trying to determine whether

the impulsive impression is true, we risk losing the opportunity

to prevent our death. If it is false and we assent without bothering to think much

about whether it is true,

we risk wasting our time trying to prevent our death.

This suggests that we should not spend time much time gathering evidence.

Maybe this explains why the Stoics think that false beliefs about what is good and what is bad give impulsive impressions their power. They dispose us to assent.

The Platonists and Aristotelians cannot use this explanation for their problem case.

What is the their problem case?

We have an impulsive impression from one of nonrational parts of the soul. This impression is not impulsive because of the beliefs of reason. So the puzzle is how this impulsive impression can exert power over reason in such a way that reason comes to assent to it.

Frede gives two examples in the Christian tradition to explain why reason assents to these impressions. They are instances of what he describes (in 25) as "rationalization."

Origen and Evagrius are the authors Frede cites.

They knew Platonist and Aristotelian tripartite theory. They are using this theory in explanation of Christian examples in which someone succumbs to temptation.

Origen and Evagrius, in this way, provide evidence for why the Platonists and Aristotelians thought reason assents to an impulsive impression from the nonrational parts of the soul.

21. We get a relatively simple and straightforward view in Origen

[of how impressions that have the source of their impulsiveness in the

nonrational part of the soul have power over reason].

Origen (2nd to 3rd century CE), Christian theologian.

De Principiis (On First Principles).

Not a great translation for our purposes, but it is freely available online.

"But if anyone should say that the impression from without is of such a sort that

it is impossible to resist it whatever it may be, let him turn his attention to his own

feeling and movements and see whether there is not an approval, assent and inclination

of the controlling faculty towards a particular action on account of some specious

attractions. For instance, when a woman displays herself before a man who has determined to

remain chaste and to abstain from sexual intercourse and invites him to act contrary

to his purpose, she does not become the absolute cause of the abandonment of that

purpose. The truth is that he is first entirely delighted with the sensation and lure of the

pleasure (πάντως γὰρ εὐδοκήσας τῷ γαργαλισμῷ καὶ τῷ

λείῳ τῆς ἡδονῆς) and has no wish to resist it nor to strengthen his previous determination;

and then he commits the licentious act. On the other hand the same experiences

may happen to one who has undergone more instruction and discipline; that is, the

sensations and incitements (οἱ μὲν γαργαλισμοὶ καὶ οἱ ἐρεθισμοὶ) are there, but his reason, having been strengthened to

a higher degree and trained by practice (ἠσκηκότι) and confirmed towards the good by right

doctrines, or at any rate being near to such confirmation, repels the incitements and

gradually weakens the desire"

(Origen, De Principiis, III.1.4; G. W. Butterworth, 1936).

Origen, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

ἄσκησις,

askēsis, noun, "exercise, practice, training"

προπάθεια,

propatheia, noun, "prepassion"

ἐρεθισμός,

erethismos, noun, "irritation"

γαργαλισμός,

gargalismos, noun, "tickling"

Didymus the Blind

4th century CE Christian theologian. Student of Origen.

"First, the devil cast it into his heart to betray the Lord, then, Scripture says,

'after the morsel

Satan entered him' [John 13:27]--not that Satan entered first, but that he

'cast into his heart' [John 13:2] an incipient passion. After he found

that the it persisted, so that it was no longer an incipient passion (προπάθειαν), but rather

the worst kind of disposition, he took a position, a place to enter into him"

(Didymus the Blind, Commentary on Ecclesiastes, 294.15).

It is based on the idea that impulsive impressions in themselves have an

agreeable or disagreeable character which, in the case of unreasonable

impressions, turns them into incipient passions (propatheiai). There

maybe something titillating about the very impression itself. Origen (De

princ. III.1.4) speaks of the tickles (gargalismoi) and

provocations (erithismoi) and also the smooth pleasure produced by

the impression. Now, you might enjoy the impression and dwell on it. And so it

will retain its force or even grow in force. It is perhaps not too far-fetched

(though Origen does not say so explicitly) to assume that your ability to form

impressions, your imagination, gets encouraged by the way you dwell on the

impression, to embellish it and make it seem even more attractive. What Origen

does say is that, if you have the appropriate knowledge and practice

(askêsis), then, instead of dwelling on the agreeable impression, you

will be able to make the impression go away and dissolve the incipient lust.

So nonrational and indeed unreasonable impulsive impressions gain some force

by our dwelling on and enjoying the agreeable character of the mere fantasy.

What is this "simple and straightforward view in Origen"?

Frede explains that thinking about the content of the impulsive impression can be enjoyable, that "you might enjoy the impression and dwell on it," and that because of this, the impression "will retain its force or even grow in force" over reason.

How is this supposed to work?

Maybe to "enjoy the [impulsive] impression and dwell on it" is to think about what would happen if you assented to it. When you do this, you see that assent will bring pleasure. "So nonrational and indeed unreasonable impulsive impressions gain some force by our dwelling on and enjoying the agreeable character of the mere fantasy."

Why?

The suggestion seems to be that the "dwelling" leads reason to have a belief about the amount of pleasure and thus to form the belief that the object of the impulsive impression is good.

Why does this happen to reason?

Reason lacks "the appropriate knowledge and practice (askêsis)." If it had this "knowledge and practice," "then, instead of dwelling on the agreeable impression, you will be able to make the impression go away and dissolve the incipient lust." You know better than to dwell on the impression and thus to put yourself in a situation in which you are tempted.

What is "incipient lust"?

The impulsive impression is the "incipient passion" (προπάθεια). The "lust" is the "passion" (πάθος) what arises if assent is given to this impulsive impression.

22. When we turn to one of the most influential ascetic writers among the

Desert Fathers,

The Desert Fathers are early Christian hermits and ascetics. They

lived mainly in the Scetes desert of the Roman province of Egypt,

beginning around the 3rd century CE.

Evagrius of Pontus (4th century CE)

Evagrius wrote on the ascetic life as a

progression of stages the monk must pass through to attain

the ultimate goal of the knowledge of God.

Evagrius fell into disrepute in the 6th century, when his writings

(and Origen's and Didymus's the Blind) were associated with a

strain of Origenism condemned at the Fifth Ecumenical Council (553 CE).

"There are three chief groups of demons opposing us in the practice of the ascetic life,

and after them follows the whole army of the enemy. These three groups fight

in the front line, and with impure thoughts seduce our souls into wrongdoing

(τὰς ψυχὰς διὰ τῶν ἀκαθάρτων λογισμῶν ἐκκαλοῦνται πρὸς τὴν κακίαν).

They are the demons set over the appetites of gluttony, those who suggest to

us avaricious thoughts, and those who incite us to seek esteem in the eyes of men"

(Appendix I, Περὶ διαφορῶν πονηρῶν λογισμῶν).

λογισμός,

logismos, noun, "counting, calculation"

Evagrius Ponticus (whose allegiance to Origen stood in the way of his having a

greater influence in theology but could not prevent his influence as a

spiritual guide), these tempting impressions are referred to as

logismoi (literally, “reasonings,” but here better translated as

“thinkings” or “considerations”). This is extremely puzzling at first sight,

as these impressions have their origin in the nonrational part of the soul or

even the body, neither of which can reason. But I have already pointed out

that we have to be careful not to overlook the fact that Aristotle, though he

denies reason to animals, does not deny animals considerable cognitive

abilities and even something which we would call thinking, namely, inferences

based on experience. It is just that Aristotle, given his elevated notion of

reason as involving understanding, does not call this “thinking.” Something

similar, mutatis mutandis, can be argued for the Stoics and even for Plato.

Correspondingly, while the nonrational part of the soul has no understanding

or insight, it is sensitive to experience and can form a view as to how

pleasant it would be to obtain something and how, to judge from experience,

one might attain it. What it lacks is understanding, especially understanding

of the good, which would allow it to understand why it would not be a good

thing to indulge in this pleasure.

There is a lot going on here.

"Animals are by nature born with the power of sensation, and from this some

acquire the faculty of memory, whereas others do not. ... The other animals

live by impressions and memories, and have but a small share of experience

(ἐμπειρίας); but the human race lives also by art and reasoning (τέχνῃ καὶ

λογισμοῖς). It is from memory that men acquire experience, because the

numerous memories of the same thing eventually produce the effect of a single

experience. Experience seems very similar to science and art, but actually it

is through experience that men acquire knowledge and art. ... Art is produced

when from many notions (ἐννοημάτων) of experience a single universal (καθόλου)

judgment is formed with regard to like objects. To have a judgement that when

Callias was suffering from this or that disease this or that benefited him,

and similarly with Socrates and various other individuals, is a matter of

experience; but to judge that it benefits all persons of a certain form

(εἶδος), considered as a class, who suffer from this or that disease (e.g.

the phlegmatic or bilious when suffering from burning fever) is a matter of

art"

(Metaphysics I.1.980a).

Plato, Aristotle, and the Stoics understand the

cognition that constitutes reason in such a way that it excludes cognition

that we would think belongs to reason.

What is the cognition their understanding excludes?

"[I]nferences based on experience."

Frede's interpretation is perhaps easiest to understand for Aristotle.

Aristotle distinguishes "reason" and "experience." When he does this in the Metaphysics, he explains the difference in terms of the medical practitioner and theorist. The practitioner judges, as matter of experience, that patients who look a certain way will benefit from a certain medicine. The practitioner has the ability to make this judgement because he is part of a tradition of observing patients and the outcomes of their treatments. Aristotle does not think that the cognition involved in the judgement the practitioner makes is an exercise of "reason."

What Aristotle understands in the appetite as a judgement from experience "as to how pleasant it would be to obtain something," Evagrius Ponticus thinks of as a "consideration" the nonrational soul supplies to reason about the pleasantness of something.

Why does Evagrius Ponticus use λογισμός for this "consideration"?

Frede thinks, it seems, that Evagrius Ponticus does not know Aristotle's distinction.

23. How can there be logismoi which have their origin in the nonrational soul, or even the body, and are able to persuade reason? One way in which this might happen is if reason believes that some pleasures are a good but is not entirely clear about whether this pleasure is a good after all. Whereas the nonrational part of the soul is not sensitive to reasons or to reasoning in this sense, reason itself is sensitive to experience and to considerations based on experience. Still, the nonrational part of the soul may learn to become quite persuasive. It might point out how pleasant it would be to obtain a certain object and how easy it would be to obtain it in this circumstance. Reason, as we know, does not require proof, let alone the kind of proof which involves understanding and insight, to be persuaded. So here is the beginning of a view as to how reason might be persuaded to give assent to a nonrational and even unreasonable impression. The nonrational part of the soul offers it considerations, things to be considered in making a choice, which might persuade reason.

Frede here is answering a question he poses in 21 and 22.

The question occurs in the context of trying to understand what the Platonists and Aristotelians would have to think to place the Stoic idea that all action requires the assent of reason within the context of a tripartite theory of the soul.

They would have to think that reason can assent to "rational" and "nonrational" impulsive impressions. The "rational" impulsive impressions are impressions whose impulsiveness derives from the beliefs of reason about what is good and what is bad. The "nonrational" impulsive impressions are impressions that have their impulsiveness a different way.

These impulsive impressions are the problem case.

This problem is really two problems.

What makes these impressions impulsive?

Why do these impressions have "power" over reason.

Frede is considering an answer to the second question.

(In 4 and 5, he seems to say that the likings and dislikings in the nonrational part of the soul are the source of the impulsiveness of these impressions.)

Frede thinks that because reason "is sensitive to experience and to considerations based on experience," there "is the beginning of a view as to how reason might be persuaded to give assent to a nonrational and even unreasonable impression." What happens is that "[t]he nonrational part of the soul offers it considerations [about how pleasant and easy it would be to do something], things to be considered in making a choice, which might persuade reason."

How is this Evagrius Ponticus view related to the Origen view Frede talks about in 21?

I am unsure, but here is the beginning of an answer.

In Origen view, the impulsive impression from one of the nonrational parts is initially not attractive to reason because reason does not believe that the object of the impression is good. As reason "dwells" on the impression, the impression becomes attractive to reason. Reason comes to think that assenting and thus pursuing the object of the impression would result in pleasure. So reason comes to believe that the object of the impression is good.

In the Evagrius Ponticus view, this "dwelling" is not part of the explanation for why reason assents. Instead, "[t]he nonrational part of the soul offers [reason] considerations."

24. There is still some puzzle as to how this is supposed to work. We have to explain how reason can be persuaded because it takes these considerations, offered by the nonrational part of the soul, to have some bearing on its own view that it would not be good to indulge in this pleasure. To take the most simple and straightforward case, we need to see why reason, when it thinks that it would not be a good thing to indulge in this pleasure, should in any way be moved by the consideration that it would be very pleasant to indulge in this pleasure. For it to be moved, the nonrational considerations would have to have, or would have to be thought by reason to have, some bearing on its own view.

What is the remaining "puzzle"?

"To take the most simple and straightforward case, we need to see why reason, when it thinks that it would not be a good thing to indulge in this pleasure, should in any way be moved by the consideration that it would be very pleasant to indulge in this pleasure."

I am not sure I understand this.

Is the question why does reason not just reject the "considerations?"

If this is the question, then it would seem that the lack of "appropriate knowledge and practice" (that Frede discusses in 21 in his discussion of Origen) is the answer.

It is a commonplace that we sometimes revise our belief that something is good when we

get the thought that it causes pain. Socrates makes the point in the Republic.

This, however, does not show that he thinks that all action requires the assent of reason

and that the phenomenon of acting on an unreasonable desire is really a matter of

reason changing its beliefs about what is good and what is bad.

"Don't you agree with me in thinking that men are unwillingly deprived of good

things but willingly of evil? Or is it not an evil to be deceived in respect of

the truth and a good to possess truth? And don't you think that to opine the

things that are is to possess the truth?

Why, yes, you are right, and I agree that men are unwillingly deprived of true opinions.

And doesn't this happen to them by theft, by the spells of sorcery or by force?

I don't understand.

I must be talking in high tragic style. By those who have their opinions stolen

from them I mean those who are over-persuaded and those who forget, because in the one

case time, in the other argument strips them unawares of their beliefs. Now I presume

you understand, do you not?

Yes.

Well, then, by those who are constrained or forced I mean those whom some pain or

suffering compels to change their minds.

That too I understand and you are right.

And the victims of sorcery I am sure you too would say are they who alter their

opinions under the spell of pleasure or terrified by some fear.

Yes, everything that deceives appears to cast a spell upon the mind.

Well then, as I was just saying, we must look for those who are the best guardians of the

indwelling conviction that what they have to do is what they at any time believe

to be best for the state. Then we must observe them from childhood up and propose

them tasks in which one would be most likely to forget this principle or be

deceived, and he whose memory is sure and who cannot be beguiled we must accept and

the other kind we must cross off from our list. Is not that so?

Yes, Socrates

(Republic III.413a).

25. But now it looks as if reason, to give assent to the nonrational

impression, would have to change its own view, in the sense that it

rationalizes into a rational impression the nonrational impression that it

would be pleasant to indulge in this pleasure—an impression of reason that it

would be good to indulge and so give assent to this rational impression and

thus, indirectly, to the nonrational impression.

This is confusing.

What is it for reason to "rationalize" a nonrational impression into a "rational impression"?

Reason "rationalizes" the impression when it "changes its own view" about what is good and what is bad based on interaction with the nonrational part of the soul.

How does this solve the problem?

I am not sure, but here is a possibility.

Because reason now has new beliefs about what is good and what is bad, the impulsiveness of the impression no longer comes only from the nonrational parts of the soul. Now reason's own beliefs make it difficult for it not to assent to the impression.

This is still a little confusing, so it helps to see what is supposed to happen in steps.

We have an impression that there is a piece of cake on the table that would be sweet to eat. This impression is impulsive, but the source of its impulsiveness is not in the beliefs in reason. Reason does not have the belief that eating sweets is good. Instead, the source of the impulsiveness of this impression is in the appetitive part of the soul. From experience, this part of the soul has developed the expectation that eating sweets is pleasant.

Next reason "rationalizes" this expectation in the appetite. Reason "change[s] its own view."

Reason comes to believe that eating sweets is good. (The process i which this happens is either the one Frede takes Origen to describe or the one he takes Evagrius to describe.) Now reason's own beliefs about what is good make it difficult for reason not to assent to the impulsive impression that there is a piece of cake on the table that would be sweet to eat.