THE MILESIAN INQUIRERS

Thales, Anaximander, and Anaximenes think about the world in a new way

Click the map to enlarge it.

Click the map to enlarge it.

For an explanation of the name Ἰωνία ("Ionia"), see Pausanias,

Description of Greece, 7.1.2.

Ancient philosophy traditionally begins with Thales of Miletus in 585 BCE.

585 BCE is a very long time ago. It is about a 100 years before Socrates was born, and it is about 2,500 years before Neil Armstrong walked on the moon in 1969.

The city of Miletus was on the coast of the Aegean Sea in the Greek region called Ionia.

Thales and Anaximander and Anaximenes (who also were from from Miletus) were part of a larger group of thinkers from Ionia that included Xenophanes and Heraclitus.

Xenophanes was born in Colophon. Heraclitus in Ephesus.

These Thinkers are Presocratics

The description "Presocratic" belongs to a way of understanding Ancient philosophy.

This understanding is old, but the term Presocratic is modern. It seems to first appear in Johann August Eberhard's (1739-1809) Allgemeine Geschichte der Philosophie (General History of Philosophy), and later it became standard with Hermann Diels (1848-1922) and the publication of his Die Fragmente der Vorsokratiker (The Fragments of the Presocratics) in 1903. Diels's work dominated scholarship for many years. The last edition was published in 1952.

The thought that there are Presocratics implies that Socrates (469-399 BCE) set the agenda for a lot of what would happen subsequently in Ancient philosophy. If we are to understand this, we have to understand how Ancient philosophy came to exist in the first place.

This is the primary reason we, in this course, are interested in the Presocratics.

The Need for a New Kind of Answer

These dates are based on reports in later in the history.

Herodotus (5th century BCE)

says

that Thales predicted a solar eclipse whose occurrence

changed the outcome of a war between the Lydians and the Medes.

The eclipse occurred in 585 BCE.

Diogenes Laertius (3rd century CE)

reports

that Apollodorus of Athens (2nd century BCE), in

his Chronology, says that Anaximander was sixty-four in 546 BCE,

that Anaximenes was his student, and that Anaximenes died in the

63rd Olympiad (528-525 BCE).

An Olympiad is four years. It is commonly represented as pair of integers (the cycle and the

year in the cycle). The first Olympiad begins in 776 BCE, so "OL 1, 1" designates 776 BCE. To

find the year BCE, a simple formula is 781 - (4 * OL + year). Since the Athenian

year begins with the summer solstice, 1 must be subtracted if the event

happened in the second half of the Athenian year. So, for example, Diogenes Laertius

reports that,

according to Apollodorus in his Chronology, Socrates was executed in

Thargelion (the eleventh month of the Athenian year) of OL 95, 1. So he died in

(781 - (4 * 95 +1)) - 1 = 399 BCE.

• Thales (late 7th to middle 6th century BCE)

• Anaximander (very late 7th to late 6th century BCE)

• Anaximenes (6th century BCE)

Dates for the early Presocratics are estimates relative to their "acme"

(ἀκμή) or "point of greatest achievement," which

conventionally is age forty. So, for example, "Thales (fl. c. 585 BCE)" assumes that the

predication of the eclipse of 585 BCE was "the point of greatest achievement"

in Thales's life and that he predicated it when he was forty.

In the words 'Thales (fl. c. 585 BCE),' the abbreviation 'fl. c.'' abbreviates

the Latin words floruit (a form of the verb

floreo ("to bloom"))

and

circa ("around").

Thales and the Milesians were part of a new way of thinking about the world.

This new thinking met a need.

Trade in the Eastern Mediterranean had made it increasingly clear that there were different ways of life and beliefs about the world and the place of human beings in it. In the light of these alternatives, the traditional answers no longer seemed so obviously correct.

This uncertainty produced a certain amount of anxiety, but this was also optimism. There was the thought that it had to be possible to develop a new kind of answer that for its defense did not rely on the weight of authority that supported the traditional stories about the gods.

In this way, in the city of Miletus in the early 6th century BCE, the circumstances were right for the emergence of a different, more objective way of thinking about the world.

To understand this new way of thinking, the first step is to see the older way.

Hesiod and the Theologists

• Hesiod (middle of 8th century BCE to middle of the 7th century BCE, younger contemporary of Homer).

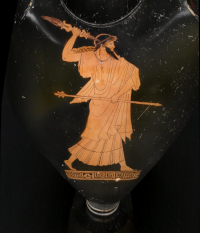

Zeus hurling a thunderbolt, amphora, 480-470 BCE.

The Cyclopes

( Κύκλωπες) gave Zeus the thunderbolt to use in the war against the Titans.

In the aftermath of the war, which the Titans lost, Zeus was allotted dominion over the sky,

Poseidon over the sea, and Pluto over Hades

(Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 1.2).

Hesiod's Theogony and Works and Days are the earliest

examples Greek "didactic" poetry.

Hesiod's Theogony and Works and Days are the earliest

examples Greek "didactic" poetry.

The adjective

διδακτικός means "apt at teaching, educational."

Hesiod's Theogony describes the origin of the world and the genealogies

of the gods.

His Works and Days offers moralizing advice, mythical

explanations of the human condition, and instruction in how to proceed in an agricultural society in daily

life and work.

Hesiod is a representative of the older way of thinking

Thales and the Milesians challenged. In the writings we associate with Hesiod,

the gods are causes of events we see in the world.

According to this older way of thinking, the following is an example (in the form of an argument) of how someone would understand why the rains come and go as they do:

1. Zeus makes the rain.

2. He wants it to rain now.

----

3. It is raining now.

The coming and going of the rains with the seasons is not an accident. It happens over and over again, and so it was thought that happened by intelligence and design.

About regular behaviors, the Greeks held this assumption about the cause with great confidence. The more modern view familiar to us would not come for a very long time.

"Zeus who thunders aloft..." (Hesiod, Works and Days 8).

As Aristotle describes the theologists, they identify the gods as the

"starting-points" (ἀρχαί) in their explanations of other things, such as

the rains. Aristotle does this too. His objection is to the

mythology, not to the existence of gods.

ἀρχή is sometimes translated as "principle" or "first principle"

because it translates into Latin as principium.

"The school of Hesiod, and all the theologists (θεολόγοι), ... make the

starting-points [in the explanations of things] gods or generated from gods"

(Aristotle, Metaphysics III.4.1000a).

Thales and the Milesian Inquirers

"Thales, the

originator of this sort of philosophy (φιλοσοφίας, genitive of φιλοσοφία), says that

[the starting-point] is water"

(Aristotle, Metaphysics I.3.983b).

"Of those [inquirers into nature] who say that the starting-point is one and movable, to whom

Aristotle applies the distinctive name of physicists (φυσικοὺς (plural accusative of the

adjective φυσικός, "one who deals with nature, a physicist")), some say it

is limited; as, for instance, Thales of Miletus, son of Examyes, and

Hippo

[of Samos] who seems also to have lost belief in the gods. These say that the

starting-point is water"

(Simplicius, following Theophrastus,

Commentary on Aristotle's Physics, 6r.18-20).

Instead of

relying on the traditional thinking, as represented in Hesiod and the theologists,

Thales, Anaximander, and Anaximenes tried to explain things in a new way.

Theophrastus (late 4th to late 3rd century BCE)

succeeded Aristotle (4th century BCE) as head of the Lyceum (Aristotle's school). Aristotle and Theophrastus are the source of

most of what is known about the Presocratics.

Simplicius of Cilicia (late 4th to mid 5th century CE) was one of the last

Platonists.

The details of his connection to the Presocratics are complicated,

but the primary points are these.

The Platonists thought of themselves as working in the philosophical

tradition that stemmed from Plato.

To understand Aristotle, who was strongly influenced by Plato, but who also

criticized Plato, the Platonists settled for a middle ground that allowed them

to treat Aristotle as an authority on logic and physics, but not on

the higher parts of philosophy. Simplicius, in discussing Aristotle,

quotes some of the Presocratic philosophers Aristotle discusses. For these

quotations, Simplicius relied on summaries in Theophrastus's work

on the Presocratics. Theophrastus's work is now almost entirely lost, but

Theophrastus's discussions of the Presocratics were summarized by Alexander of

Aphrodisias. (Alexander of Aphrodisias (second to third century CE) was an

Aristotelian commentator who aimed to articulate and defend Aristotle's

philosophy.) These summaries too are now lost, but Simplicius preserved some extracts

in his discussions of Aristotle. He and the

Platonists generally knew and consulted Alexander's work in their attempt to incorporate

Aristotle's philosophy in their reconstruction of the true philosophy Plato

had been the last to glimpse.

They tried to explain "natural" phenomena (as we now describe the phenomena in our debt to them) in terms of what they understood as "nature" (φύσις).

Their effort became known as "the inquiry into nature" (ἡ περὶ φύσεως ἱστορία).

Explanations in terms of Nature

The evidence for this interpretation depends primarily on Aristotle (who was born in 4th century BCE, roughly 200 years after the solar eclipse Thales predicted).

Aristotle refers to the Milesians as φυσιολόγοι and to the theologists as θεολόγοι (Metaphysics I.5.986b; III.4.1000a), "those who talk about nature" and "those who talk about the gods."

Anaximenes is someone "who talks about nature."

"[He] declares that the underlying nature... is air. It differs in rarity and density according to the things it becomes. Rarefied, it becomes fire; condensed, wind, then cloud, and more condensed, water, then earth, then stones, and the rest come to be out of these" (Simplicius, following Theophrastus, Commentary on Aristotle's Physics, 6r.46-50 = DK 13 A 5 = D 1).

This understanding of rain, when it is presented as an argument, takes the following form:

1. Rain is condensed air.

2. The air is condensed now.

----

3. It is raining now.

Anaximenes makes no mention of the gods. He explains rain in terms of "the underlying nature" of reality he identified as "air." This challenged the traditional understanding of regularity in nature in terms of the actions of Zeus and the pantheon of gods.

This challenge, as we will see, did not overturn the traditional assumption. Plato and Aristotle do not endorse the explanations in terms of the traditional gods in Hesiod and the theologists, but they still continued to explain regularity in terms of minds or intellects.

The Birth of a Philosophical Tradition

The Greek words that transliterate (map from character to character) more or less as "philosophy" and "philosopher"

are φιλοσοφία and φιλόσοφος. These words are rare in the surviving Greek

literature until about the time of

Plato in the 4th century BCE.

φιλοσοφία transliterates as philosophia

φιλόσοφος transliterates as philosophos

Given this explanation, when we say that "Ancient philosophy traditionally

begins with Thales," we are not saying that he was the first philosopher in this tradition.

Thales is thus unlikely to have called himself a φιλόσοφος, and although there is some indeterminacy in what we count as philosophy, it is easier to see philosophy in the reaction to the Milesian explanations than in these explanations themselves. Trade had made it clear that there were different beliefs about which gods exist and how they behaved. This caused dissatisfaction with traditional accounts and a desire for an understanding that did not depend on the weight of tradition for its authority. Thales and the Milesian inquirers responded to this desire, and the Ancient philosophical tradition seems to have emerged out of this response when questions arose about what frees an explanation from the weight of tradition.

We can see this question in Parmenides. His thought is the subject of the next lecture.

The high price of translations and the editions of the Greek and Latin texts was

an obstacle

in the study of Ancient philosophy.

During my lifetime, this obstacle has been partly overcome. Thanks to generous

grants

and the dedication of many

individuals,

translations and editions of theses texts are now freely available

on the internet.

Perseus Digital Library (a library of literature and culture of the Greco-Roman world)

Hesiod's Theogony, Works and Days

The noun ἱστορία was the traditional term for an investigation that aims for

understanding. It transliterates into English as historia, and it eventually came to be

used primarily for historical investigations involving people.

This was due in part to the influence of the

Histories

of Herodotus (484-425 BCE). He describes his conclusions as the result of an

"inquiry." In his opening sentence, he announces that "[t]his is the display of

the inquiry (ἱστορίης) of Herodotus of Halicarnassus, so that things done by man

not be forgotten in time, and that great and marvelous deeds, some displayed by

the Hellenes, some by the barbarians, not lose their glory, including among

others what was the cause (αἰτίην) of their waging war on each other." As topic

sentences go, not many are more beautiful.

In Plato's Phaedo, Socrates says that although he

came to reject the inquiry into nature,

he was once very interested in it. "When I was young, Cebes, I

was tremendously eager for the kind of wisdom which they call inquiry about

nature (περὶ φύσεως ἱστορίαν)"

(Phaedo 96a).

The noun φύσις transliterates as physis. In an older way of thinking,

φύσις is what the science of physics is about.

The translation of φύσις in English as nature is through the earlier

translation of φύσις into Latin as

natura.

The journal Nature, the top venue for most sciences,

takes its name from the object of the inquiry into nature.

Another barrier to the study of Ancient philosophy was access to a

dictionary.

The unabridged A Greek-English Lexicon was not only

very expensive but was over a thousand pages long. This made it about a foot or so thick and thus hard to use.

Now it is available online in a searchable format.

This considerably cuts the time and difficulty for use.

We do not need to think much in this course about the language in which

the Greek philosophers wrote, but I provide links to the dictionary meanings

of some words (and some of their Latin translations) because they are

interesting.

Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott,

A Greek-English Lexicon

αἰτία, aitia, noun, "accusation"

αἴτιος, aitios, adjective, "responsible"

ἀρχή, archē, noun, "beginning"

θεολογία, theologia, noun, "science of the divine"

θεολογικός, theologikos, adjective, "relating to the science of the divine"

θεολογικός is a denominative (adjective formed from a noun) of θεολογία.

For other examples of the use of the suffix -ικός to form adjectives, see Smyth

858.6a.

Herbert Weir Smyth's

A Greek Grammar for Colleges

(published in 1920) is a standard source for Greek Grammar.

θεόλογος, theologos, noun, "one who discourses about the gods"

ἱστορία, historia, noun, "inquiry"

σοφία, sophia , noun, "wisdom"

φιλοσοφία, philosophia, noun, "love of wisdom"

"Philosophy (philosophia), if you wish to translate the word, is

nothing other than the love of wisdom"

(Cicero, On Duties II.5)

"[I]t is true that the mother of all good things is wisdom, from whose love philosophy found

its name in a Greek word"

(Cicero, Laws I.58.)

φυσικός, physikos, adjective, "natural, (φυσικός is a denominative of φύσις)

φυσιόλογος, physiologos, noun, "one who discourses about nature"

φύσις, physis, noun, "nature"

θεόλογος and φυσιόλογος are compound words

θεός ("god") + λόγος ("discourse")

φύσις ("nature") + λόγος ("discourse"). λόγος is a noun derived from the verb

λέγω ("say, speak")

Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short,

A Latin Dictionary:

natura, noun, "nature"

principium, noun, "a beginning" (Latin translation of ἀρχή)

sapientia, noun, "wisdom" (Latin translation of σοφία)

studium, noun, "a busying one's self about"

Arizona State University Library. Loeb Classical Library:

Hesiod's

Theogony,

Works and Days

Early Greek Philosophy, Volume II: Beginnings and Early Ionian Thinkers, Part 1

Cicero, On Duties

Internet Archive (digital library of internet sites and other cultural artifacts in digital form):

Die Fragmente Der Vorsockratiker, Hermann Diels

Essays on Ancient Philosophy, Michael Frede

Simplicii in Aristotelis Physicorum libros quattuor priores commentaria, Hermann Diels

I am not concerned in these lecture notes with the scholarly commentary, but in

the end sections I sometimes include passages from Michael Frede's work that

have influenced the way I have come to think about Ancient philosophy.

Frede's understanding of philosophy as a historical phenomenon is an example.

"Philosophy is a historical phenomenon. It emerges out of a need to have a

certain kind of answer to certain questions, for instance questions as to the

origin of the world as we know it.

It obviously would be very frightening to live in a world in which the

behavior of things, especially where it affected one's life, seemed completely

unintelligible. There were traditional answers available to such questions, in

fact, various traditions provide answers. But these answers were in conflict

with one another.

The "traditions and their conflict" is a subject of discussion in Herodotus, who was born in the Persian

Empire in the 5th century BCE. He reports, for example, that because the Egyptians

live in a place very different from the rest of the world, they

have "customs and laws contrary for the most part to those of the rest of mankind"

(Histories II.35).

"Egyptians" (Αἰγύπτιοι)

Thus, as people became aware of the different traditions and

their conflict, the traditional answers began to fail to satisfy people's need

to feel they have a secure understanding of the world in which they live, of

nature, of social and political organizations, of what makes communities and

individuals behave the way they do. What were needed were answers of a new

kind, answers that one could defend, that one could show to be superior to

competing answers, that one could use to persuade others, so as to reestablish

some kind of consensus"

(Michael Frede, "The Philosopher," 3. Greek thought: A Guide to Classical Knowledge, 3-16.

Harvard University Press, 2000).