BECOMING LIKE GOD

Aristotle's Theory of the "For Something" in Nature

Aristotle thinks that specific behavior (the behavior common to the species) has a teleological explanation. It happens "for something and because it is better" (Physics II.8.198b).

In the case of reason, Aristotle thinks that human beings naturally acquire this ability in the process of induction as they change from children to adults. Induction changes human beings as they mature so that they become like the first unmovable mover. Aristotle thinks that its existence is good and that other things naturally change to become like it.

Aristotle develops his teleology against the background of the explanations in the Timaeus. He follows Plato in thinking that the explanation of order must be in terms of a mind. This drives them both to understandings of the world that can seem strange and implausible to us. As, though, we can see in Aristotle's remarks, they both were working against the background of a then ordinary and widespread thought that we even today is not completely opaque.

"It has been handed down from the ancients of the earliest times and bequeathed to posterity in the shape of a myth that the heavenly bodies are gods (θεοί) and that the god (τὸ θεῖον) embraces the whole of nature (τὴν ὅλην φύσιν). The rest was added mythically for the persuasion of the many about custom and for what is advantageous. They say that these gods are human in form or like some of the other animals, and make other statements consequent upon and similar to those which we have mentioned" (Metaphysics 12.8.1074b).

Teleological Causation in Plato's Universe

"There is something which must be considered first about the entire heaven or cosmos or if there is any other name which it specially prefers, by that let us call it. We must first investigate concerning it this fundamental question that must be considered at the outset in relation to anything: whether it always was with no beginning in generation or has come to be having originated from some beginning. The cosmos has come to be, for it is both visible, tangible and it has a body, and all such things are perceptible, and all perceptible things are grasped by opinion and the senses and, as we said [Timaeus 27d], come into being and are generated. What’s more, we say that a thing which has come to be has, of necessity, come to be through some cause. Now to discover the maker and father of this universe is a task indeed, and having discovered him it is impossible to describe him to everyone" (Timaeus 28b). In the Timaeus, as we have seen, there is an explanation for why things are the way they are.

"Let us state the reason why becoming and the universe were constructed by the artificer. He was good, and in the good no envy ever arises about anything and, being devoid of envy he desired that all things be as much like himself as possible" (Timaeus 29d).

"Let us conclude our discussion of the auxiliary causes that gave our eyes the

power they now possess. We must next speak of that supremely beneficial

function for which the god gave them to us. As my account has it, our sight

has proved to be a source of supreme benefit to us, in that none of our

present statements about the universe could ever have been made if we had

never seen any stars, sun or heaven. The ability to see the periods of

day-and-night, of months and of years, of equinoxes and solstices, has led to

the invention of number, and has given us the idea of time and opened the path

to inquiry into the nature of the universe. These pursuits have given us the

love of wisdom, a gift from the god to the mortal race whose value neither has

been nor ever will be surpassed. This is the supreme good our eyesight offers

us. ... The god invented sight and gave it to us so that we might observe the

orbits of intelligence in the universe and apply them to the revolutions of

our own understanding. For there is a kinship between them, even though our

revolutions are disturbed, whereas the universal orbits are undisturbed. So

once we have come to know them and to share their ability to make correct

calculations according to nature, we should stabilize the straying revolutions

within ourselves by imitating the completely unstraying revolutions of the

god"

(Timaeus 46e).

One way the divine maker ensures that human beings are like him, and thus are

good, is by ensuring that they have the sense of sight. Through this

sense human beings make themselves better by making their minds more

orderly. Timaeus thinks that seeing is part of a process that gives rise to

the love of wisdom and that ultimately transforms human beings so that their

thinking "imitat[es] the completely unstraying revolutions of the god." This god is the

universe. The universe is alive. The divine maker makes it as a soul within a body.

Teleology without the Divine Maker

Timaeus's teleological explanation is the immediate antecedent for Aristotle's idea that human beings acquire reason for the sake of becoming like the first unmovable mover.

Aristotle removes the divine maker, but not the teleology, from Timaeus's explanation.

In the Metaphysics XII, Aristotle argues that there can be no first or last moment of time, that time is an attribute of change, and that the ultimate cause of the changes that occur in the universe (such as the development of reason in induction) must be free from the possibility of change. Otherwise, Aristotle argues, "if its substance is potentiality, there will not be eternal motion, since that which exists potentially may not exist" (Metaphysics XII.1071b).

This conception of time and change rules out a teleological explanation of things in terms of a divine maker understood on the model of an artificer as Plato presents it in the Timaeus, but Aristotle does not reject teleological explanation itself. In the place of the divine maker, Aristotle thinks that "the first mover, which is immovable" (τὸ πρῶτον κινοῦν ἀκίνητον) is the starting-point for the teleological explanation of change in the universe.

Teleological Causation in Aristotle's Universe

The Fixed Stars:

Most of the visible objects in the night sky appear to move together in the same

relative arrangement night after night. These objects are the fixed stars. They

appear to lie on a spherical surface surrounding the earth and to rotate about

the north-south axis once per sidereal day.

A sidereal day (a day relative to the stars) is the time it takes for the

earth to rotate once on its axis so that the fixed stars appear to return to

their prior locations. A solar day is about four minutes shorter.

Stars rising seen looking to the East

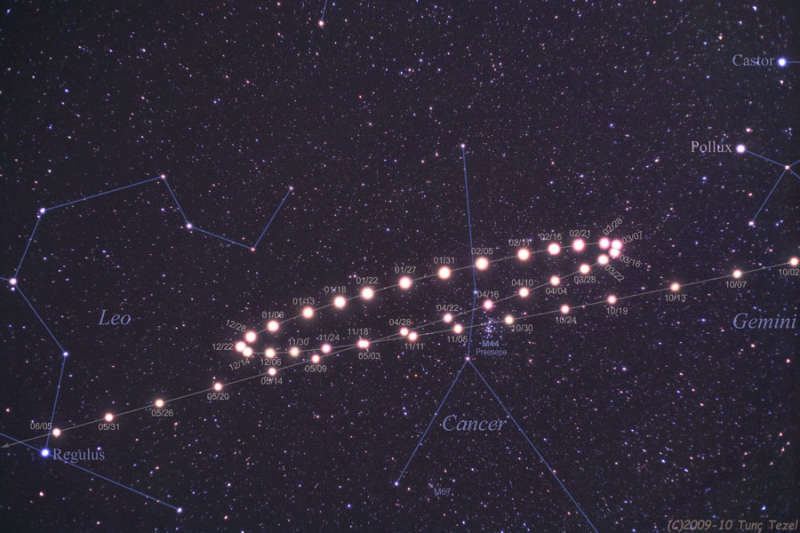

The Wandering Stars:

Relative to the fixed stars, some of the visible objects (the planets)

appear to move differently. They are the "wandering stars"

(ἀστέρες πλανῆται). In terms of spheres, their apparent motion is more

difficult to explain. One way to model the motion is terms of nested spheres.

Retrograde motion of Mars

"In order that time

might come into being, Sun, moon and the five other stars (ἄστρα) which are called wanderers (πλανητά) were

generated [by the god] to define and protect the numbers of time"

(Timaeus 38c).

"All the unwandering stars have

come into being, divine everlasting creatures which abide forever, revolving in the same way in

the same place. But those that turn back and keep wandering in this fashion have come into being

in the manner we described before"

(Timaeus 40b).

In the universe, as Aristotle understands it, there is

an outermost sphere

with earth at its center. This is the sphere of the fixed (as opposed to wandering) stars

in the heavens.

Aristotle explains the motion of the fixed stars teleologically.

These fixed stars (to us on earth appear to) move with a continuous circular motion, and Aristotle thought the first unmovable mover is the teleological cause of this motion. It causes this motion without itself changing in any way. Aristotle thought that eternally moving in a circle is a behavior in which the fixed stars engage because this is how they make their existence like the perfect existence the first unmovable mover enjoys.

Argument for the First Unmovable Mover

Aristotle's argument for the existence of the first unmovable mover runs as follows.

Because motion is an attribute of time and there is no first or last moment of time, there must be eternal and continuous motion. This motion is the circular motion of the fixed stars and what we see when we look to the heavens. This motion must have a cause, and because the motion is eternal and cannot change, the cause must be "eternal and immutable."

"There must be some substance which is eternal and immutable. Substances are the primary reality, and if they are all perishable, everything is perishable. But motion cannot be either generated or destroyed, for it always existed; nor can time, because there can be no priority or posteriority if there is no time. Hence as time is continuous, so too is motion; for time is either identical with motion or an affection of it. But there is no continuous motion except that which is spatial, of spatial motion only that which is circular" (Metaphysics XII.7.1071b).

"There is something eternally moved with an unceasing motion, and this unceasing motion is circular motion. This is evident not only argument but also in fact [since we see this motion]. The first heaven [of the fixed stars], then, must be eternal, and something must move it. Since that which is moved and moves is intermediate, there must be a mover which moves without being moved, it itself being eternal, substance, actuality" (Metaphysics XII.7.1072a).

"[This actuality is the] "first mover, which [itself] is immovable" (Metaphysics XII.7.1074a).

The Realm Below the Sphere of the Heavens

In the realm below the heavens, sensible substances do not exist eternally and so have ways of becoming like the first unmovable mover other than eternally moving in a circle.

Acquiring reason in induction is an example. It is caused teleologically. Acquiring reason in induction is a way human existence naturally becomes like the existence of the first unmovable mover. Acquiring reason and its knowledge is a step in the direction of the θεωρία or "contemplation" that characterizes the life and existence of the first unmovable mover.

"[The first unmovable mover] is the starting-point upon which the heaven and nature depend. Its life is like the best which we temporarily enjoy. It must be in that state always, which for us is impossible.... Actuality is thought to be the intellect the divine possesses, and contemplation is that which is most pleasant and best. ... If, then, the state the god always enjoys is as great as that which we enjoy sometimes, it is marvelous; and if it is greater, this is still more marvelous. Nevertheless it is so. Moreover, life belongs to god. For the actuality of intellect is life, and god is that actuality; and the essential actuality of god is life most good and eternal. We hold, then, that god is a living being, eternal, most good" (Metaphysics XII.7.1072b).

The Forms of Sensible Substances

The form of a sensible substance is thus not just an organization of material.

It is an organization for the sake of the existence of something that (as much as the material allows) has an existence like the perfect existence of the first unmovable mover.

One such organization is the form of a human being. Human beings, because of the forms that are their natures, develop reason as they become adults. This is good for them, and it is not a coincidence that they develop reason as they mature and that the development of reason is good for them. It is part of knowing what a form in matter is, according to Aristotle, that the first unmovable mover exists and is the teleological cause of regularities in nature.

"First, then, we must speak of food and reproduction; for the nutritive soul belongs to all other living creatures besides man, and is the first and most widely shared faculty of the soul, in virtue of which they all have life. Its functions are reproduction and the assimilation of food, as a living thing that has reached its normal development and is unmutilated, and whose mode of generation is not spontaneous, naturally produces another like itself, an animal producing an animal, and a plant a plant, in order that, as far as its nature allows, it may partake in the eternal and divine (τοῦ ἀεὶ καὶ τοῦ θείου). Each strives for this and for the sake of this performs all its natural functions. ... However, since they cannot share in the eternal and divine by continuity of existence, because no perishable thing can remain numerically one and the same, they share in these in the only way they can, some to a greater and some to a lesser extent; what persists is not the individual itself, but something in its image, not one in number but one in form" (On the Soul II.4.415a). This is true for the nonhuman animals and plants too. They "partake in the divine" by reproducing and thus by making another like themselves. It is not a coincidence that they have this behavior and that it is good for them. The behavior is their way of being like the unchanging existence of the first unmovable mover. Aristotle says that "since they cannot share in the eternal and divine by continuity of existence, because no perishable thing can remain numerically one and the same, they share in these in the only way they can."

Our Thinking is Different Now

It does appear that members of species have their specific behavior because it benefits them, but to us the details of Aristotle's explanation for this are no longer at all plausible.

Plato and Aristotle saw gods when they looked up to the sky.

Against the charge that he does not believe in the traditional gods, Socrates replies that he with the rest of mankind believes that "the sun and the moon are gods" (Apology 26d).

This outlook is no longer as compelling as it once was because we no longer are so ready to insist that the explanation of order and regularity must be in terms of something intelligent.

This is one of the most significant ways in which human thinking has changed over time.

Perseus Digital Library

Plato,

Timaeus.

Aristotle,

Metaphysics.

Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon

κόσμος, kosmos, noun, "order"

"Aristotle thinks that we can argue from the fact that there always has been

motion and always will be motion and that there is no beginning or end to

time, that there must be at least one continuous eternal and hence cyclical

motion. Hence there must be at least one eternal body which eternally moves

continuously in a cycle. To account for this motion we have to assume a mover

which eternally moves the body. But such a mover must itself be immaterial,

not subject to any change or motion. So we have at least two items, an eternal

body in eternal periodic motion, and an immaterial unmoved mover. These two

items are minimally necessary, Aristotle argues, for there always to be change

and for there always to be time"

(Michael Frede, "Introduction," 30-31. Aristotle's Metaphysics Lambda, 1-52).

"In general, if we consider the divine intellect of Aristotle and its primacy [primauté], we

think about a first mover that moves the celestial sphere and, in this way, indirectly, the stars and

sublunary things. But we should remember that in the thought of Aristotle, God is bound much more intimately and directly

to the being and behavior of sublunary things. In the Metaphysics (L, 7, 1072a26-27 ff.), the first mover moves as the

Prime Intelligible [premier intelligible] and the Prime Desirable [premier désirable]. How does Aristotle

think of it as the Prime Desirable? In De an., II, 4, 415b1, he explains the reproduction of plants and animals by

their desire for the divine. He argues that, therefore, all the natural behavior of these living beings are due to the divine.

Obviously the plants have no desires in the strict sense. And animals, even if they have desires, do not want the divine in the

sense that we could say that they want something to eat. But in their behavior they follow a plan finalized for their reproduction

and thus their perpetuation, if not as individuals, at least as a species. Thus, they are able to participate in the eternal and

divine as much as possible for plants and animals. What matters here is that Aristotle argues that it is the Divine itself that

guides the animals in their behavior by guiding them in their desires. Thus the divine operates inside of animals as it provides

some structure and content to those desires.

As for human beings, how they participate in the divine as much as possible seems evident. It is in thinking, specifically

thinking eternal theoretical truths and, finally, this fundamental theoretical truth, the existence of God, that we participate in the

divine as much as we can. All our natural behavior and also our natural desires are aimed at achieving this end. Thus the divine gives

structure and content to our desires that can only be explained in relation to it.

But human beings are endowed with reason. They are guided by desires of reason. Thus, not only human desires in general, but also the thought of

practical reason must have a structure and content that is used to realize the end and that can only be explained in relation to God. But if that end

is constituted ultimately by the contemplation of God and theoretical science, human thought in general must have a structure and content that

conforms to this purpose. It is therefore both desires and thoughts that are intelligible only in relation to this end and so in relation to God"

(Michael Frede, “La théorie aristotélicienne de l’intellect agent.” Translation by Samuel Murray).

"Arguably Aristotle takes his primary philosophy to be the counterpart of

Plato's dialectic. As is clear from Met. Z[VII].16 1040b27-1041a13,

Aristotle thinks that in a way Plato was right in postulating immaterial separate

forms, except that he was wrong in the way he identified them, namely as

Platonic ideas, rather than as eternal substances, namely immaterial intellects

of the kind Aristotle discusses in Met. Λ[XII]. The place of the idea

of the good [in Plato] will be taken by the first unmoved mover. Moreover, Aristotle in

arguing that, and trying to show how, primary philosophy is universal, somehow

deals with whatever there is quite generally, though it has a specific domain,

namely unchanging separate substances, is just mirroring the Platonic

assumption that dialectic, though concerned specifically with the forms, provides

universal knowledge, given that the forms are the principals of everything"

(Michael Frede, "Aristotle's Account of the Origins of Philosophy," 42.

Rhizai. A Journal for Ancient Philosophy and Science, 2004, 9-44).