SUBSTANCE MOST OF ALL

The development of Aristotle's thinking about substance

The chronological order of the works in the Aristotelian corpus is uncertain, but the

Outline of Categories 1-5:

Chapter 1. Names

Chapter 2. The division of reality

Chapter 3. Predicates

Chapter 4. The ten categories

Chapter 5. Substance

Categories (the first of the logical works) appears to be among

Aristotle's earliest works.

Aristotle talks about "substances" (οὐσίαι) in the Categories, but he makes no mention of forms in matter. This suggests that his thinking about substances in the Categories had not yet taken the turn we have seen in some parts of his Physics, On the Soul, and Metaphysics.

The Ontology in the Categories

"Of the beings: some are said of a subject but are not in any subject. Man is

said of a subject, this or that man, but is not in any subject. Some are in a

subject but are not said of any subject. By in a subject, I mean what is in something,

not as a part, and cannot exist separately from what it is in.

For example, knowledge-of-grammar is in a subject, the soul, but is not

said of any subject; and is in a subject, the body (for all color

is in a body), but is not said of any subject.

Some are said of a subject

and in a subject. For example, knowledge is in a subject, the soul, and is

said of a subject, knowledge-of-grammar. Some are neither in a subject

nor said of a subject, for example, this or that man or this or that horse—for nothing

of this sort is either in a subject or said of a subject. Things that are

individual (ἄτομα) and one in number (καὶ ἓν ἀριθμῷ) are, without exception, not

said of any subject, but there is nothing to prevent some of them from being

in a subject. Knowledge-of-grammar, for example, is one of the things in a

subject"

(Categories 2.1a).

"A substance--that which is called a substance most strictly,

primarily, and most of all--is neither said of a subject nor in

a subject, e.g. this or that man or this or that horse. The

species in which the things primarily called substances are, are

called secondary substances, as also are the genera of these

species. This or that man belongs in a species, man, and animal is a genus of

the species; so these--both man and animal--are called secondary substances"

(Categories 5.2a).

In the Categories, to identify the

parts of reality terms in the language signify,

"All the other things are either said of the primary substances

as subjects or in them as subjects. ... So if the primary substances

did not exist it would be impossible for any of the other things to exist"

(Categories 5.2a).

This is why οὐσία gets translated into English substance.

The Latin noun substantia is

derived from a participle of verb substare. This verb

means "to stand under."

"It is reasonable that, after the primary substances, their

species and genera should be the only other things called secondary substances.

For only they, of things predicated, reveal the primary

substance. For if one is to say of this man what he is, it will be appropriate to

give the species or the genus as the answer (though more informative to give man than

animal); but to give any of the other things would be out of place--to say, for example,

that he is white or that he runs or anything like that"

(Categories 5.2b).

Aristotle is correcting the ontology in the Phaedo.

"Let us then, Cebes, turn to what we were discussing before. Is the

reality itself (αὐτὴ ἡ οὐσία), whose reality we give an account in our

dialectic process of question and answer, always the same or is it liable to

change? Does the equal itself, the beautiful itself, what each thing itself is, the reality, ever

admit of any change whatsoever? Or does what each of them is, being uniform and existing

by itself, remain the same and never in any way admit of any change?

It must necessarily remain the same, Socrates.

But how about the many things, for example, men, or horses, or cloaks, or any other such

things, which bear the same names as those objects and are called beautiful or

equal or the like? Are they always the same? Or are they, in direct opposition to those others,

constantly changing in themselves, unlike each other, and, so to speak, never the same?

The latter, they are never the same.

And you can see these and touch them and perceive them by the other senses,

whereas the things which are always the same can be grasped only by the

reasoning of the intellect,

and are invisible and not to be seen?

Certainly that is true.

Now, shall we assume two kinds of existences, one visible, the other invisible?

Let us assume them, Socrates"

(Phaedo 78c).

In Aristotle's ontology in the Categories,

"the equal itself, the beautiful itself" are general properties and so

are not substances at all, neither primary nor secondary substances.

Socrates in the Phaedo implies that man is a substance. Aristotle downgrades it to a secondary substance.

Socrates does not call the the "men" and the "horses" substances.

Aristotle makes them primary substances.

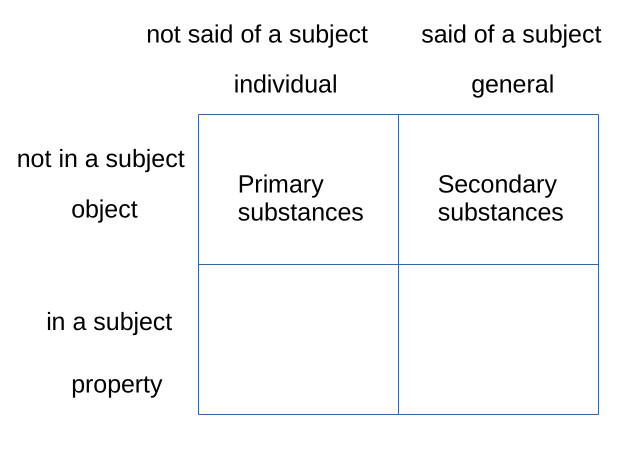

Aristotle divides "the beings" (τὰ ὄντα) according to whether they are "said

of a subject" or "in a subject."

This partitions reality into four kinds of beings. To refer to them, although Aristotle himself does not use these terms, we can call the kinds of beings in this partition (i) individual objects, (ii) individual properties, (iii) general objects, and (iv) general properties.

The individual objects are the most fundamental of the four. The other beings depend on these objects for their existence. To mark this, Aristotle calls these beings "primary substances."

To see some of the implications of this ontology, consider the following two sentences:

Socrates is a man.

Socrates is white.

The term 'Socrates' in these sentences signifies an individual object, Socrates. The term 'man' signifies an object too. According to Aristotle, 'man' signifies a general object, man.

This can be surprising. It is natural to think that individual human beings exist and that Socrates and Plato are men, but man does not exist in addition to the many men.

Aristotle's understanding of the truth of the second sentence can be surprising too.

He thinks that if this sentence is true, there is an individual property the term 'white' signifies. Further, this individual property is in the individual object the term 'Socrates' signifies.

Finally, as we will see in the next section, Aristotle's understanding of individuality is also surprising. He thinks Socrates, as an individual, is an indivisible part of the object man.

The Oneness of Individuals

To begin to understand what Aristotle is thinking, we start from the philosophical problem he is trying to solve. Socrates is one thing, not some things heaped together. The philosophical problem is to explain this oneness. Aristotle knows this, and he tries out an explanation.

The objects ("this or that man or this or that horse") Aristotle identifies as primary substances are the "atomic" parts of general objects. They are indivisible and hence are individuals.

"For the primary substances, it indisputably true that each signifies a this; for the thing revealed is individual [or "atomic" (ἄτομον)] and one in number" (Categories 5.3b).

Aristotle thinks the general object animal is divisible into more specific general objects, such as man. Man is not further divisible into general objects, but it is divisible into the many individual men (Socrates, Plato, and so on). These men are indivisible (because the parts of human beings are not human beings) and hence they are the "atomic" parts of the object man.

This, for Aristotle in the Categories, is what it is for Socrates to be "one in number."

Problems in the Ontology

When we read the Categories is an early work, Aristotle appears to think again about substance in his Physics, On the Soul, and Metaphysics. In these later works, he appears to believe that the "this or that man" of the Categories do not meet the conditions for being a substance.

We can see how this might happen. The "this or that man" in the Categories is a concrete object. It is some human being with

We ordinarily think that it is possible for Socrates to become pale, but it is not clear that this change can be accommodated within the ontology

in the Categories. We need something more basic than Socrates as

what persists, but there is nothing in the ontology to play this role.

"[W]hat is most characteristic of substance appears to be this: that,

although it remains, notwithstanding, numerically one and the same, it

is capable of being the recipient of contrary qualifications. Of

things that are other than substance we could hardly adduce an example

possessed of this characteristic. For instance, a particular color,

numerically one and the same, can in no wise be both black and white,

and an action, if one and the same, can in no wise be both good and

bad. So of everything other than substance. But substance, remaining

the same, yet admits of such contrary qualities. One and the same

individual at one time is white, warm or good, at another time black,

cold or bad. This is not so with anything else"

(Categories 5.4a).

a certain height, weight, and so on. So when we think about the ontology, we might wonder what "this or that

man" is such that it is a subject distinct from its accidents

(the height, weight, and other properties it possesses).

The development of Aristotle's thought remains a matter of considerable debate among historians, but there is general agreement that the primary substances in the Metaphysics are not the primary substances of the Categories. The "this or that man" in the Categories are familiar from experience. They are concrete objects of a certain size, weight, color, and so on.

Aristotle, in his later works, rethought the ontology he set out in the Categories.

Aristotle came to doubt the existence of the general objects ("man" and "horse") he identified as secondary substances in the Categories, and he took steps to work out a new explanation of the oneness of "this or that man" and of what a substance is more generally.

Thinking again about Substance

Now we can see little more clearly why Aristotle proceeds in the Metaphysics as he does.

It is natural to think that as we live our lives, Socrates and the other individuals we meet are real. Once, however, we identify them as primary substances, we must explain how they are separate from their accidents. If, because we think we cannot give this explanation, we conclude that they are not the primary substances, it is not clear what is.

In the Metaphysics, to answer this question, Aristotle sets out conditions for substance ("this," "subject," and "separate") and investigates whether anything meets them.

The general objects ("man" or "horse") Aristotle identified in the Categories as secondary substances do not meet these conditions. The same is true for the individual objects ("this or that man" and "this or that horse") he identified as primary substances.

So, with Plato in his background, Aristotle investigates whether there might a way of thinking about forms so that they meet the three conditions for being a substance.

We can get some insight into Aristotle's investigation if we imagine that he thinks about concrete objects to discover what in them meets the conditions for being a substance.

Socrates can exist without any particular height and weight, but he must have some height and weight or other. He is a concrete object, and so cannot exist without properties, but maybe there is a way to think about the organization of flesh, blood, and so on, that makes Socrates be a human being so that this organization is a "this," "subject," and "separate."

Forms are Substances

We can also begin to see that thinking about how the forms of natural bodies are substances would lead Aristotle to think that these forms are substances with qualification.

Aristotle thinks that a soul (the form of a living natural body) is a substance with qualification because it is a "first actuality." It is an organization that contains unrealized potentialities. Human beings have the potential to walk, but this potential is not always actualized.

This suggests that Aristotle is working with the possibility that existence as an actuality without potentiality is the fundamental way of being a form and a substance.

This, if the interpretation is right, provides some insight into how first philosophy is universal.

If divine substances are forms, it falls to theology as first philosophy to explain what existence as a form is. The explanation will be that forms exist as actualities that do not involve any potentialities. They are "pure" actualities. Further, because the explanation of existence as a "pure" actuality includes an explanation of existence as an "impure" actuality (an actuality involving potentialities and so an actuality with qualification), theology explains the existence or being of the forms in matter that physics studies when it studies sensible substances.

This helps show what Aristotle was thinking, but questions about the details remain. Many of these questions do not have answers, mostly because Aristotle himself did not know what to say, but we will look at one last detail before we turn to his thought in the ethical works.

Perseus Digital Library

Aristotle,

Metaphysics

Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon

ἀκίνητος, akinētos, adjective, "immovable"

ἄτομος,

(ἀ

+

τέμνω), atomos, adjective, "uncut"

μεταβολή, metabolē, noun, "change"

μεταβάλλω, metaballō, verb, "turn about, change, alter"

χωριστός, chōristos, adjective, "separable"

Arizona State University Library: Loeb Classical Library.

Aristotle, Categories,

Physics I-IV

"In the Metaphysics, Aristotle denies that there is anything

general--at least, he denies that there are kinds [animal, man, and so on] into

which objects fall. Thus, he also abandons the notion of an individual which he

had relied on in the Categories, since it presupposes that there are

general things, that there are universals"

(Michael Frede, "Individuals in Aristotle," 50.

Essays in Ancient Philosophy, 49-71).

"In the Metaphysics, Aristotle denies that there are genera or species

[animal, man] that is, he denies that universals really exist (cf.

[Metaphysics] Z 13). Yet, if there are no genera and species,

individuals no longer can be taken to be the ultimate, indivisible [or "atomic"]

parts of genera [as he claimed in the Categories]"

(Michael Frede, "Individuals in Aristotle," 63.

Essays in Ancient Philosophy, 49-71).

"[In the Metaphysics, Aristotle] sees that it cannot be the ordinary

objects of experience [this or that man, this or that horse] that underlie the

properties, if there are to be properties in addition to the objects; for the

ordinary objects of experience are the objects together with their

properties—an ordinary object has a certain size, weight, temperature, color,

and other attributes of this kind. So, if we ask what is it that underlies all

these properties and makes them the properties of a single object, we

cannot answer: just the object. For the object, as ordinarily understood,

already is the object together with all its qualities; what we, however, are

looking for is that which underlies these qualities. Thus we can see why

Aristotle now considers answers like 'the form' or 'the matter' when

considering the question, what actually is the underlying substance"

(Michael Frede, "Individuals in Aristotle," 64.

Essays in Ancient Philosophy, 49-71).

"Although [in the Metaphysics] he retains the primary

substances of the Categories, namely objects, these must now

yield their status as primary substances to their substantial forms

which now come to be called primary substances. The substantiality of

concrete particulars [this or that man] is thus now only secondary. The

idea of the Categories that substances are that which underlies

everything else is retained, as we see from Metaphysics] Z 1

and Z 3. However, the answer to the question what is it that underlies

everything else has changed: now it is the substantial form"

(Michael Frede, "The Title, Unity, and Authenticity of the Aristotelian Categories,"

26. Essays in Ancient Philosophy, 11-28).

"Aristotle thinks that substances are not as such

composite. There are substances that are pure forms, as e.g., the unmoved mover.

And it is clear from [Metaphysics] Z 3,1029 b 3ff. and Z 11, 1037 a

10ff. (cf. also Z 17, 1041 a 7ff.) that Aristotle thinks that the discussion of

composite substances in [Metaphysics] Z [and Metaphysics] H is

only preliminary to the discussion of separate substances. We start by

considering composite substances because they are better known to us, we are

familiar with them, and they are generally agreed to be substances. But what is

better known by nature are the pure forms. Aristotle's remarks suggest that we

shall have a full understanding of what substances are only if we understand the

way in which pure forms are substances. This, in turn, suggests that he thinks

there is a primary use of 'substance' in which 'substance' applies to forms.

Particularly clear cases of substance in this first use of 'substance' are pure

forms or separate substances. It is for this reason that composite substances

are substances only secondarily"

(Michael Frede, "Substance in Aristotle's Metaphysics," 79.

Essays in Ancient Philosophy, 72-80).

"[S]ubstantial forms rather than concrete objects are the basic entities.

Everything else that is depends on these substantial forms for its being and

for its explanation. Hence substantial forms, being basic in this way, have a

better claim to be called 'ousiai' [οὐσίαι] or 'substances' than anything

else does. Some of them are such that they are realized in objects with

properties. But this is not true of substantial forms as such. For there are

immaterial forms. Properties, on the other hand, cannot exist without a form

that constitutes an object. Moreover, though certain kinds of forms do need

properties for their realization, they do not need the particular properties

they have. The form of a human being needs a body of a weight within certain

limits, but it does not need that particular weight. No form needs that

particular weight to be realized. But this particular weight depends for its

existence on some form as its subject. In fact, it looks as if Aristotle in

the Metaphysics thought that the properties, or accidental forms, of

objects depended for their existence on the very objects they are the

accidental forms of, as if Socrates' color depended on Socrates for its

existence. However this may be, on the new theory [in the Metaphysics

that supercedes the theory in the Categories] it is forms that exist

in their own right, whereas properties merely constitute the way forms of a

certain kind are realized at some point of time in their existence"

(Michael Frede, "Substance in Aristotle's Metaphysics," 80.

Essays in Ancient Philosophy, 72-80).