Epicurus and the Garden

A Move Away from the Rationalism of Plato and Aristotle

Epicurus, 341-270 BCE.

Hermarchus, 4th to 3rd century BCE.

Successor to Epicurus as head of the

school. Works are lost.

Lucretius, first century BCE.

Roman poet

and author of On the Nature of Things. Explains the principles of Epicureanism in Latin verse.

Epicurus's Garden was on the

road from the Dipylon gate to the Academy

(Cicero, On Ends 5.1.3).

The Diplyon gate was the main gate in the wall around Athens.

Themistocles (Athenian general)

built it when rebuilt and fortified Athens after the Persian

Wars.

Diogenes Laertius (3rd century CE) preserves three letters from and Epicurus and lists the forty-one titles of Epicurus's "best" books

(Lives of the Philosophers X.

27).

These titles are all we have of these books.

What we know about Epicurus depends primarily on the three letters.

Epicurus's

school is "the Garden" (ὁ κῆπος). It was an estate just outside the city walls

he purchased in about 306 BCE.

Socrates had been dead for about 100 years.

Few of Epicurus's writings have survived. His philosophy became unpopular, and hence was not passed on, as the critical reaction to the classical tradition gave way to the resurgence of non-skeptical forms of Platonism and to the subsequent rise of Christianity.

The Good Life and Happiness

Epicurus thinks the key to happiness is "four-fold remedy" (τετραφάρμακος).

"For who do you believe is better than a man who has pious opinions about the gods, is fearless about death, has diligently considered the natural goal of life and understands that the limit of good things is easy to achieve completely and easy to provide, and that the limit of bad things has a short duration or causes little trouble" (Epicurus, Letter to Menoeceus X. 133).

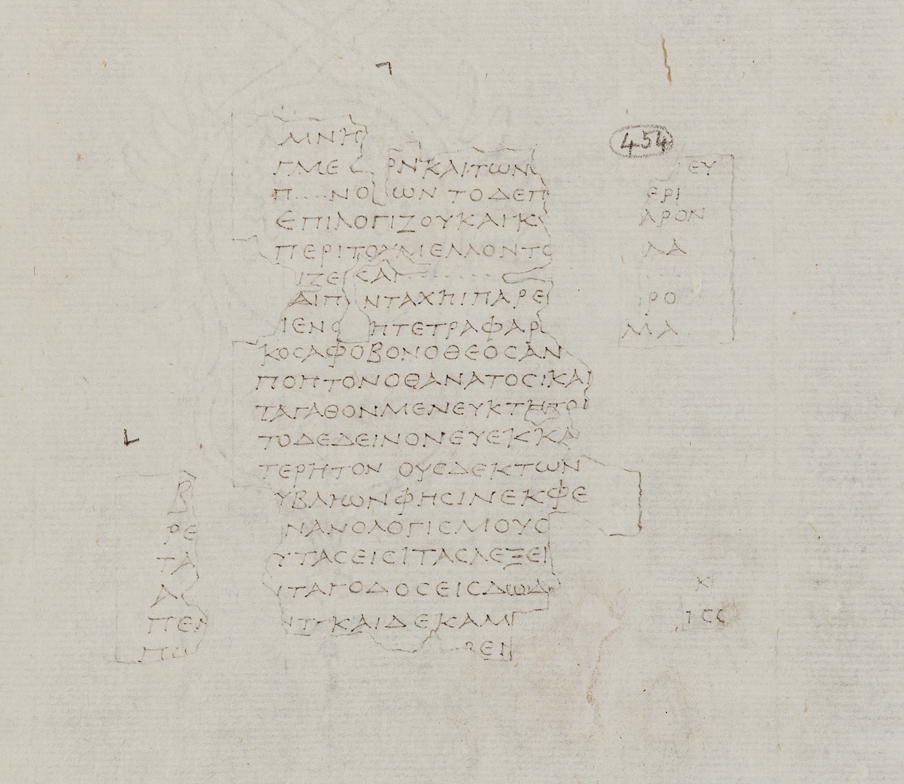

The τετραφάρμακος: "God presents no fears, death no worries, and while good is readily

attainable, bad is readily endurable" (Philodemus of Gadara, preserved in

Herculaneum Papyrus 1005, 4.10–14)

Philodemus, Herculaneum Papyrus, 1005.

Discovered at the Villa of the Papyri in Herculaneum.

This is not easy to read, in part because it is written in unicals (a form of

majuscules or large letters) without the word individuation and punctuation

to which we are accustomed. Here it is (beginning on the ninth line of the

text) in majuscules in a more readable form:

ΑΦΟΒΟΝ Ο ΘΕΟΣ, ΑΝΥ

ΠΟΠΤΟΝ Ο ΘΑΝΑΤΟΣ, ΚΑΙ

ΤΑΓΑΘΟΝ ΜΕΝ ΕΥΚΤΗΤΟΝ,

ΤΟ ΔΕ ΔΕΙΝΟΝ ΕΥΕΚΚΑΡ

ΤΕΡΗΤΟΝ

In minuscules, it is:

ἄφοβον ὁ θεός, ἀνύποπτον ὁ θάνατος, καὶ τἀγαθὸν μὲν

εὔκτητον, τὸ δὲ δεινὸν εὐεκκαρτέρητον.

We get the word τετραφάρμακος from Epicurus's 1st century BCE follower, Philodemus of Gadara. The

text in which it occurs was discovered in the 18th CE archeological excavations at

Herculaneum (one of the towns buried in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE).

A τετραφάρμακος is "drug, or medicine, with four parts." In the context of Epicurus's thought, the τετραφάρμακος cures the misery that plagues human life. Taking the τετραφάρμακος makes us εὐδαίμων. In Greek, this is how someone is when he is living the good life. Happy is the translation we have been using to translate this adjective.

Diogenes of Oenoanda (a 2nd century CE follower) was so impressed with the τετραφάρμακος that in his city of Oenoanda (in the southwest of Turkey) he had a wall erected and inscribed with Epicurus's philosophy for the benefit of the public.

The Four-Fold Remedy

Epicurus advances the τετραφάρμακος as a solution to life's most worrying problem.

We worry about ourselves as we live, but taking the τετραφάρμακος shows us that there is an easy-to-execute and effective plan for living that is overwhelmingly likely to result in a life for us in which the pleasure we experience vastly outweighs the pain.

The τετραφάρμακος is thus a source of immense relief and satisfaction. It removes the worry we have for ourselves and our life, and it shows us that the few bad things that can happen are unlikely to be disturbing enough to undermine our peace of mind and happiness.

God presents no fears

"There are some who have supposed that we have arrived at the thought of

gods from marvellous happenings. This opinion seems to

have been held by Democritus, who says that when the men of old saw things

happen in the heavens, such as thunderings and lightnings, and thunderbolts

and collisions between stars, and eclipses of sun and moon, they were

frightened, imagining the gods to be the causes of these things"

(Sextus Empiricus, Against the Physicists 1.24).

The first part of the τετραφάρμακος is that "God presents no fears."

This part of the cure consists in sufficient knowledge of physics and the nature of the gods to dispel the fears mythology reinforces and that undermine our happiness.

This shows us the relation of knowledge of reality to the good life is is not the view in Plato and Aristotle. For Epicurus, this knowledge is just to remove superstition.

Fears of the sorts described in mythology haunt human beings. About natural phenomena we do not understand, we make up threatening stories. We think these phenomena indicate divine mood and that storms and other such phenomena are punishment from the gods. Knowledge of physics and the nature of the gods is necessary to dispel the fears enshrined in mythology and thus to correct the unfortunate and all too common tendency of human beings to form distressing but false beliefs about the world and their place within it.

[D]eath [presents] no worries

"Accustom yourself to think that death is nothing to us, for good and bad are

in sentience, and death is the privation of all sentience;

therefore a right understanding that death is nothing to us makes the

mortality of life enjoyable"

(Epicurus, Letter to Menoeceus

X.

124).

The second part of the τετραφάρμακος is that "death [presents] no worries."

Epicurus explains that the fear of death stems from a false belief about what happens to us in death. He argues that in reality death is "nothing to us."

1. Something is bad for us only if we suffer when it is true.

2. The dead do not suffer (because they do not feel anything at all).

3. If (1) and (2) are true, then death is "nothing to us."

----

4. Death is "nothing to us."

The argument shows us that really the fear of death is nothing more than one of the many superstitions to which human beings are prone and that undermine their happiness.

[G]ood is readily attainable, bad is readily endurable

"Of desires some are natural, others are groundless;

of the natural some are necessary as well as natural, and some natural only.

And of the necessary some are necessary if we are to be happy, some if the body

is to be rid of uneasiness, some if we are even to live. He who has an unwavering

understanding of these things will direct every preference and aversion toward securing

health of body and tranquillity (ἀταραξίαν) of soul, seeing that this is the sum and end of a

blessed life"

(Epicurus, Letter to Menoeceus

X.

127).

"[The Epicureans] say that the stable and settled condition of the flesh and the trustworthy expectation of this

condition contain the highest and the most assured delight for men who can

reckon"

(Plutarch, Moralia.

That Epicurus Actually Makes a Pleasant Life Impossible,

1089d).

Plutarch, Platonist, 1st to 2nd century CE

"While therefore all pleasure because it is naturally akin to us is good,

not all pleasure is choice worthy, just as all pain is an evil and yet not all

pain is to be shunned. It is, however, by measuring one against another, and by

looking at the conveniences and inconveniences, that all these matters must be judged"

(Epicurus, Letter to Menoeceus

X.

129).

"When we say that pleasure is the end, we do

not mean the pleasures of the prodigal or the pleasures of sensuality, as we

are understood to do by some through ignorance, prejudice, or wilful

misrepresentation, but [we mean that the end is] the absence of pain in the

body and of trouble in the soul. It is not an unbroken succession of drinking-bouts and of

revelry, not sexual love, not the enjoyment of fish and the other delicacies

of a luxurious table, that produces a pleasant life; it is sober reasoning,

searching out the grounds of every choice and avoidance, and banishing those

beliefs through which the greatest tumults take possession

of the soul"

(Epicurus, Letter to Menoeceus

X.

131).

This part of the τετραφάρμακος gives us the correct understanding of the good life.

Epicurus thought that living the good life is a matter of having a certain pleasure of the mind he called "tranquillity" (ἀταραξία). He thought that to have this pleasaure, we should restrict our desires to those that are natural and necessary. These are the desires we fulfill in a life of moderation, not excess. A life of excess is difficult to achieve and likely to be punctuated with extreme unpleasantness, but if we live a moderate life, the things we need are "readily available" and the few bad things that do happen are small and "readily endurable."

Against the Classical Tradition

The stress on memory in Epicurus suggests that he is allied with an empiricist tradition.

"Tranquillity is to be released from all these [troubles] and to have a continual remembrance of the general and most important points [I have set out]" (Letter to Herodotus, X. 82).

This "remembrance" is not what happens in the good life according to Plato and Aristotle.

Aristotle, as we saw, thought that the good life is activity of the part of the soul with reason in accordance with its proper virtues. He thought that the best of these virtues is wisdom, that wisdom is the virtue proper to the part of the soul with reason that grasps what cannot be otherwise, that someone with wisdom has knowledge of the reality of things, and that the activity in accordance with wisdom is the contemplation of this knowledge.

This "contemplation" is an exercise of what Plato and Aristotle called reason. The "continual remembrance" in Epicurus is something he tries to understand in terms of memory.

Whenever someone with "continual remembrance" of the four-fold remedy thinks about what to do, he experiences "tranquillity," not worry for himself in the future. When he thinks about what to do, a thought comes to his mind. He thinks "God presents no fears, death no worries, and while good is readily attainable, bad is readily endurable." This "remembrance" causes him to experience "tranquillity" (ἀταραξία), because it eliminates his anxiety about the future and causes him to believe that he is going to experience more pleasure than pain.

"The cry of the flesh is not to be hungry, not to be thirsty, not to be shivering. Someone who has satisfied these cries of the flesh and expects to satisfy them in the future could compete even with the great god Zeus in happiness" (Vatican Sayings, 33).

The Vatican Sayings are 81 maxims attributed (not always correctly) to Epicurus. They were discovered in 1888 in a 14th century Vatican manuscript about which little is known.

Experience, Reason, and Knowledge

"Those who rely on experience only are called empiricists.

Similarly, those who rely on reason are called rationalists.

And these are the two primary sects in medicine.

The one proceeds by experience to the discovery of medicines, the other by means of

indication. And thus they named their sects empiricist and rationalist. But they also

customarily call the empiricist sect observational and relying on memory and the

rationalist sect dogmatic and analogistic"

(Galen (130-210 CE), On the Sects for Beginners

I.65 ).

"empiricists" (ἐμπειρικοί), "rationalists" (λογικοὶ)

In what survives of his work, Epicurus does not work out his epistemology

in much detail. What he says, though, seems to confirm that he sees himself as part of an

empiricist tradition.

The empiricists opposed the rationalism in Plato and Aristotle. They questioned whether we need to recognize a power of mind that grasps universals that give us knowledge of consequence and incompatibility that we can exhibit in a deductive theory.

The following example helps make the issue a little clearer.

Suppose that all human beings we and others have known have always been mortal. Is this enough for us to know that all human beings are mortal?

It would not be for Aristotle because he thought that knowledge requires that we grasp the relation of consequence between being a human and being mortal.

We might, as an empiricist, counter that we gain nothing by positing a power of mind to grasp this relation and that instead we can account perfectly well for our knowledge that all human beings are mortal in terms of our sense experiences and our memory of them.

In this empiricist approach to knowledge, the experiences we retain in memory produce certain beliefs. When the human beings of which we have had experience (either directly ourselves or through the reports of others who had experiences of them) turn out to be mortal, our memory produces in us the belief that all human beings are mortal. Further, because of how we form this belief, it counts something we know given that its propositional content is true.

Some Evidence for Empiricism in Epicurus

There is not much textual evidence, as so little of Epicurus's work survived, but we can some indications of this empiricist view about how to account for knowledge.

Preconceptions are Recollections

One is that he makes what he calls "preconceptions" (προλήψεις) a function of memory.

These preconceptions correspond to the knowledge Aristotle thought human beings acquire when they acquire reason through the process of induction as they become adults.

Epicurus, unlike Aristotle, does not talk about reason and its knowledge.

"By preconception they mean a sort of apprehension or a right opinion or notion, or universal idea stored in the mind; that is, a memory of an external object often presented, e.g. such and such a thing is a man" (Diogenes Laertius, Lives of the Philosophers X.33).

This sounds like a view Socrates says he thought about when he was young.

The view about the brain Socrates is wondering about seems to go back

to Alcmaeon of Croton (6th century BCE). He was part of the Ancient medical tradition

that was interested in the nature of knowledge as part of an effort to defend the claim of medicine to be a real

"art" (τέχνη).

"Reasoning is a kind of memory combined with things apprehended with the

senses"

(Hippocrates of Cos (father of medicine, 5th century BCE), Precepts

1).

"Turn next to the second division of philosophy,

that of method and of dialectic, which is termed λογική. Of the whole armour of

logic, Epicurus is absolutely destitute. He does away with definition;

he has no doctrine of division or partition; he gives no rules for deduction or syllogistic

inference, and imparts no method for resolving dilemmas or for detecting fallacies of equivocation.

The criteria of reality he places in sensation"

(Cicero, On Ends I.22).

"They will not get Epicurus, who despises and laughs at the whole of dialectic"

(Cicero, Academica II.97).

"He scorns dialectic, which contains the entire science of

discerning what each thing entails, of judging of what kind each

thing is, and of arguing methodically"

(Cicero,

On Ends II.18).

"The Epicureans reject dialectic as superfluous, explaining that it is

sufficient for physicists to proceed in accordance with the words attached

to things. In On the Criterion [a lost work], accordingly, Epicurus affirms that our sensations

and preconceptions and our feelings are the criteria of truth"

(Diogenes Laertius, Lives of the Philosophers

X.

31).

"The empiricists argue that no art has any need for dialectic"

(Galen, On the Sects for Beginners

I.77).

"Is it the blood, or air, or

fire by which we think? Or is it none of these, and does the brain

furnish the sensations of hearing and sight and smell, and do memory

and opinion arise from these, and does knowledge come from

memory and opinion in a state of rest?"

(Phaedo 96a).

Dialectic is Superfluous

Epicurus also rejected dialectic, and this too suggests that he sees himself as part of the empiricist attempt to understand knowledge and reason that Plato mentions in the autobiography passage in the Phaedo and associates with the inquirers into nature.

In rejecting dialectic, what Epicurus rejects is the rationalist understanding of what we ordinarily call our knowledge and our reasoning. When we see a human being, we do not know he is mortal because we have exercised a power of mind the rationalists call reason. We know that he is mortal because of our memory of our experiences of human beings.

Similarly, when we make mistakes in reasoning, Epicurus does not explain this by saying that we have an inadequate grasp of the real relations dialectic helps us organize into a theory. He thinks that we go wrong because we uncritically accept thoughts that sensation occasions. The sensations themselves are never false, but we can inadvertently form false beliefs if we are not careful to subject the thoughts the sensations occasion to confirming and disconfirming.

"Falsehood and error always depend upon the intrusion of opinion" (Letter to Herodotus, X.50).

"Error would not have occurred [in our beliefs], if we had not experienced some other movement in ourselves, conjoined with, but distinct from, the sensation of what is presented. From this movement, if it be not confirmed or be contradicted, falsehood results; while, if it be confirmed or not contradicted, truth results" (Letter to Herodotus, X.51).

We have a perception. It prompts us to think that some proposition is true, but we should not simply believe this proposition is true. Epicurus thinks that this sort of uncritical acceptance is what leads to false beliefs, not our failure to use dialectic as the rationalists understand it.

Epicurus and the Empiricist Tradition

This suggests that although the empirical tradition Plato and Aristotle rejected largely disappeared from the historical record, it did not go out of existence. It shows up in Epicurus.

Later in the tradition, this empiricist tradition shows up again in Pyrrhonian Skepticism.

This movement is outside the timeline of this course (which comes to an end with the Period of Schools in about 100 BCE), but I give some explanation of its origin in the last lecture.

Perseus Digital Library

Plato,

Phaedo

Diogenes Laertius,

Lives of Eminent Philosophers

Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon

ἀπολαυστός, apolaustos, adjective, "enjoyable,"

ἀπολαύω, apolauō, verb, "have enjoyment of [a thing],"

ἀταραξία,

(ἀ ("not")

+

ταράσσω ("trouble, disturb"), ataraxia, noun, "impassiveness, calmness,"

θόρυβος, thorybos, noun, "noise, uproar, clamour"

ἐπιλογίζομαι, epilogizomai, verb, "reckon over, conclude, consider,"

ταραχή, tarachē, noun, "disorder, disturbance, upheaval,"

τετραφάρμακος, tetrapharmakos, adjective, "compounded of four drugs"

Arizona State University Library. Loeb Classical Library:

Diogenes Laertius,

Lives of Eminent Philosophers. Volume II: Books 6-10

"Epicurus' Letter to Herodotus, for instance, is replete with references to

memory. He tells us to remember firmly the basic principles of Epicureanism,

in fact to memorise them. What is behind these admonitions does not seem to be

just the trivial view that if one wants to be an Epicurean one had better

remember the basic tenets of Epicureanism, but rather the view that our whole

way of thinking is determined by our memory, by what we remember having

experienced and what we have committed to memory in the, perhaps wrong, belief

that it is the case. It is tempting to think that Epicurus' rejection of

dialectic or logic is related to this (see D.L. x.31). As

understood by Platonists, Peripatetics or Stoics, dialectic or logic, as we

noted earlier, is based on the assumption that there are certain relations

between terms or propositions, or rather their counterparts in the world, such

that in virtue of these relations certain things follow from, or are excluded

by, other things. Dialectic teaches us to see these sometimes complex

relations and to reason accordingly. In fact, this is what it is to reason, to

argue on the basis of one's adequate or inadequate grasp of, or insight into,

these relations. So when Epicurus rejects dialectic, one is inclined to assume

that he is rejecting this rationalist view of thought and inference, just

as the empiricists reject dialectic for this, too"

(Michael Frede, "An Empiricist View of Knowledge: Memorism," 240-241.

Companions to Ancient Thought. I. Epistemology, 221-246.

Cambridge University Press, 1990).