ZENO AND THE STOICS

Thinking Again about Socrates

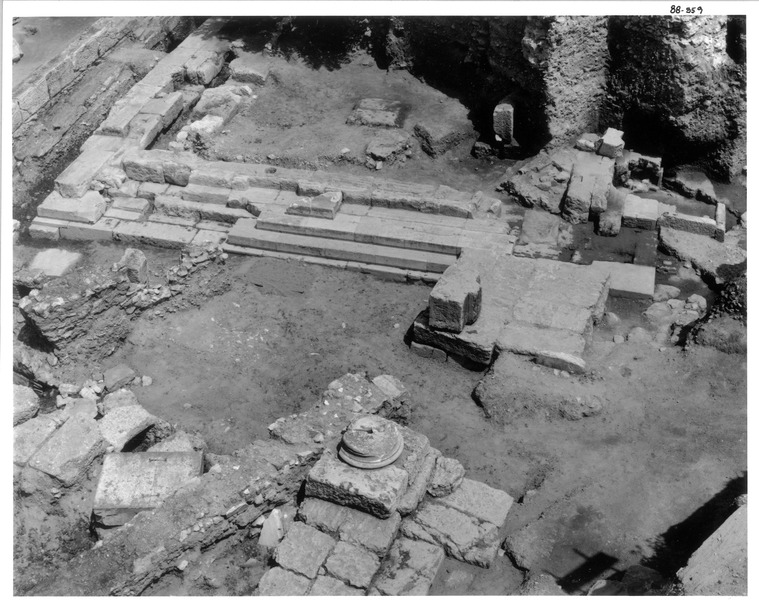

Steps of the Ποικίλη Στοά, north-west corner of the

Agora,

the central square in Athens. In the foreground is what remains of the foundation of the Hellenistic Gate (which

allowed access to the Agora from the north).

Early Stoicism:

Zeno of Citium,

late 4th to middle 3rd century BCE.

Founded the school in about 300 BCE.

Cleanthes,

late 4th to late 3rd century BCE.

Succeeded Zeno as head of the school.

Chrysippus,

early 3rd to late 3rd century BCE

Third and most influential head of the Stoic school.

Middle Stoicism:

Panaetius of Rhodes,

late 2nd to early 2nd century BCE.

Succeeded Antipater of Tarsus in about 129

BCE to become the seventh head of the Stoic school in Athens.

Posidonius of Apameia,

2nd to middle 1st century BCE.

Late Stoicism:

Seneca, late 1st century BCE to middle 1st century CE.

Epictetus,

middle 1st to late 2nd century CE.

Marcus Aurelius, 121-180 CE. Roman

Emperor, 161-180.

The Stoics take their name from their meeting place in the

Ποικίλη Στοά ("Painted Colonnade").

A στοά ("stoa") is a roofed colonnade. The Ποικίλη Στοά was

known for its murals.

Aeschines (4th century BCE Attic orator) says that the Greek victory in 490 BCE over the Persians at the Battle of Marathon

was pictured there

(Against Ctesiphon III.186).

The early Stoics wrote a lot, but almost none of it has survived.

By the middle of the 3rd century CE, because Stoicism no longer attracted practitioners, no one had a motive to preserve the texts. The Platonists (on whom we depend for most of the texts that have survived) saw no need to preserve them since they did not think these texts helped them understand the truth they thought Plato came the closest to seeing.

As a consequence, our knowledge of early Stoicism depends mostly on what others wrote.

The Soul in the Adult is Reason

The Hellenistic philosophers were united in their critical reaction against the philosophy of Plato and Aristotle. For the Stoics, this took the form of looking back to the philosophy of Socrates and not developing his thought in the way Plato did and Aristotle followed.

We can see this with respect to the tripartite theories of the soul in Plato and Aristotle.

Whereas Plato and Aristotle thought Socrates was wrong to think the soul is reason, the Stoics thought he was right. They thought that although a human being begins life with a soul without reason, this soul is transformed into reason when he becomes an adult.

So, like Socrates, the Stoics are intellectualists about desire. Cicero makes the point:

After Caesar was assassinated in 44 BCE, Cicero (106-43 BCE) tried but was unsuccessful in opposing Antony.

Cicero himself was murdered not long after, but in the last years of his life,

he turned to writing philosophy. The dictatorship of Caesar had forced him out

of public life, and his personal life was also in disarray. (In 46 BCE, he

divorced his wife (with whom he had a marriage of convenience) and married a

younger woman. This marriage ended in less than a year, in part because of his

grief over the death in childbirth of his daughter from his first marriage.)

Unable to serve the people through politics, Cicero decided

he would serve them by setting out Greek philosophy in his native

Latin. His writing is a primary source for much of the thought of the

Hellenistic philosophers.

"Whereas the ancients claimed the passions are

natural and have nothing to do with reason, ... Zeno would not agree with that.

He thought these commotions were equally voluntary and arose from a

judgment which was a matter of mere opinion"

(Cicero, Academica I.39).

Cicero has in mind Plato and Aristotle as the "ancients" who thought the "passions" (πάθη) belong to the nonrational parts of the soul. Zeno, Cicero says, thought that was wrong.

Zeno thought the "passions" are a matter of "judgement" and "opinion."

To understand what he meant, the place to begin is the Stoic theory of impressions.

The Stoic Theory of Impressions

The Stoics thought that animals and human beings have "impressions" (φαντασίαι).

"An impression is an imprint on the soul" (Diogenes Laertius, Lives of the Philosophers VII.45).

The impression is a representation of what impressed itself, and it is easy enough to see in a general way what the Stoics thought. When someone says "I have the impression that the color of this webpage is white," we ordinarily do not find this hard to understand.

Impressions are not restricted to sensory impressions. In adults, they arise in thinking too. We can, for example, have them about the future or what is true in mathematics.

Impressions in adults are such that the adult thinks about the thing as the thing, a shade of white as a shade of white, a human being as a human being. Animals and children do not because they lack reason. Their impressions somehow represent in terms of images.

Further, unlike animals and children, adults can "assent" (συγκατάθεσις) to their impressions. Assent to an impression results in belief in the propositional content of the impression.

The Stoics make what they called "cognitive" and "impulsive" impressions play a special role in how human beings represent the world and act in terms of these representations.

"[Diocles says that] the Stoics like to give their account of

impression and sense perception first,

given that the criterion by which the truth of things is known is

is generically an impression, and also because the theory of

assent and that of cognition and thought, which precedes all the

rest, cannot be stated apart from impression"

(Diogenes Laertius, Lives of the Philosophers

VII.

49).

Diocles of Magnesia wrote a work entitled Survey of the Philosophers

that Diogenes Laertius excerpts in his Lives of the Philosophers. Apart from these

excerpts, nothing is known about Diocles or his work.

"Among the impressions, some are rational and others nonrational. Those of

rational creatures are rational; those of nonrational creatures are nonrational"

(Diogenes Laertius, Lives of the Philosophers

VII.51).

"The Stoics say that an animal’s first impulse is to preserve itself, because nature

from the start makes the animal attached to itself....

For pleasure, if it is really felt, they declare to be a

by-product, which never comes until nature by itself has sought and found the

means suitable to the animal's existence; it is an aftermath comparable to the

condition of animals thriving and plants in full bloom. And nature, they say,

regulates the life of plants too, in their case without impulse and sensation,

just as also certain processes go on of a vegetative kind in us. But when in

animals impulse has been superadded, whereby they are enabled to go in quest

of their proper sustenance, for them the rule of nature is to

follow the direction of impulse. But when reason by way of a more perfect

leadership has been bestowed on the beings we call rational, for them life

according to reason rightly becomes the life according to nature. For

reason intervenes as the craftsman of impulse"

(Diogenes Laertius, Lives of the Philosophers

VII.85).

Some Impressions are Impulsive

The Stoics appeal to "impulsive impressions" (φαντασίαι ὁρμητικαί) in their explanation of what goes on in the soul when animals, children, and adults undertake some action.

Some of the impressions in animals and children impel them and thus put them in motion. This happens, according to the Stoics, because nature is provident. Nature constructs animals and children so that they naturally maintain themselves. Nature arranges things so that when animals and children have certain impressions, they have certain "impulses" (ὁρμαί). The impressions cause the animals and children to behave in ways conducive to their survival. When, for example, they have the impressions they are hungry, they move to eat.

The Stoics thought that when a child becomes an adult, although behavior in the adult occurs in terms of impulsive impressions, assent is now necessary for these impressions to issue in impulses. Assent is a function of reason. Animals and children cannot assent because they do not have reason, but they also have no need to assent. For them, nature in its providence arranges things so that their impulsive impressions automatically issue in impulses in them.

The Stoics thought that impulsive impressions in the adult are impulsive against the background of beliefs about what is good and bad. In this , they followed Socrates. Like Socrates, they thought these beliefs are desires and the source of motivation in adults.

An example makes it easier to understand this Stoic view about what goes on in the soul.

Suppose that someone has the impression that the coming plunge in the overnight temperature will kill his tomato plants. If he believes that their death is bad, then this impression that the cold will kill them is impulsive for him. If he assents to this impulsive impression, he has the impulse to take steps to prevent his tomato plants from dying from the cold.

Some Impressions are Cognitive

"The criterion of truth they say is the cognitive impression"

(Diogenes Laertius, Lives of the Philosophers

VII.

54).

"When a man is born, the Stoics say, he has the commanding-part of his soul

like a sheet of paper ready for writing upon. On this he inscribes each of his

conceptions. This begins with the senses. For by

perceiving something, e.g., white, they have a memory of it when it has

departed. And when many memories of a similar kind have occurred, we then say

we have experience. For the plurality of similar impressions is experience.

Some conceptions arise naturally in the aforesaid ways and undesignatedly,

others through our own instruction and attention. The later are called

conceptions only, the former are called preconceptions

as well"

(Pseudo-Plutarch,

Placita 4.11; LS 39 E).

The Stoics appeal to

"cognitive impressions" (φαντασίαι καταληπτικαί) in their theory of knowledge

and their explanation of what goes on in the life in which we are happiest.

How the Stoics understood cognitive impressions is not straightforward, but we can make some progress by first considering how they understood the development of reason.

The Stoics thought that human beings naturally develop reason as they become adults. In this, they followed Aristotle against Plato. Children initially lack reason and have the same kind of impressions as nonhuman animals, but as they mature they naturally develop "preconceptions" of colors, shapes, and other simple perceptual features of reality. More complex preconceptions arise naturally (according to the providence of nature) from these simple ones.

"Reason ... is said to be completed from our

preconceptions during our first seven years"

(Pseudo-Plutarch, Placita 4.11).

"And reason, when it is full grown and

perfected, is rightly called wisdom"

(Cicero,

On the laws I.7).

The Stoics took reason to consist in these preconceptions and the

basic truths about the world they embody. These truths form the basis

for the recognition of consequence and incompatibility and thus for the

ability to make inferences and hence to reason.

This is the epistemological thesis we saw in Plato and Aristotle. It is part of the preconception of a human being that there is a relation of consequence between being human and being mortal. The adult, as he has reason, can conclude that the human beings he sees are mortal.

Cognition, Opinion, and Knowledge

"And if the impression had been grasped in such a way that it

could not be dislodged by reason, Zeno called it knowledge"

(Cicero,

Academica I.41).

"Knowledge they say is steadfast cognition

or a state which in reception of impressions cannot be shaken by

argument. Without the study of dialectic, they say, the wise man cannot guard

himself in argument so as never to fall"

(Diogenes Laertius,

Lives of the Philosophers VII.47).

"[A cognitive impression] being plainly evident and striking, lays

hold of us, almost by the very hair, as they say, and drags us off to assent,

needing nothing else to help it to be thus impressive or to suggest its

superiority over all others. For this reason, too, every man, when he is anxious

to apprehend any object exactly, appears of himself to pursue after an

impression of this kind—as, for instance, in the case of visible things, when he

receives a dim impression of the object. He intensifies his gaze and

draws close to the object of sight so as not to go wholly astray, and rubs his

eyes and in general uses every means until he can receive a clear and striking

impression of the thing under inspection, as though he considered that the

credibility of the cognition depended upon that"

(Sextus Empiricus, Against the Logicians I.257).

"[A]ccording to the Stoics the cognitive impression is judged to be cognitive

by the fact that it proceeds from an existing object and in such a way as to

bear the impress and stamp of that existing object; and the existing object is

approved as existent because of its exciting a cognitive impression"

(Sextus Empiricus, Against the Ethicists 183).

"An impression is an imprint on the soul: the name having been appropriately

borrowed from the imprint made by the seal upon the wax. Of impressions, some

are cognitive and some are not cognitive. The former, which the Stoics say is the

criterion of reality, is defined as that which proceeds from a

real object, agrees with that object itself, and has been imprinted

seal-fashion and stamped upon the mind: the latter, or noncognitive, that

which does not proceed from any real object, or, if it does, fails to agree

with the reality itself, not being clear or distinct"

(Diogenes Laertius,

Lives of the Philosophers VII.1.45).

"Sphaerus [a Stoic who studied with Zeno] went to Ptolemy Philopator at Alexander. One day there was a discussion about whether a wise man would allow himself to be

guided by opinion, and when Sphaerus affirmed that he would not, the king, wishing to refute him,

ordered some pomegranates of wax to be set before him; and when Sphaerus was deceived by them, the

king shouted that he had given his assent to a false impression. But Sphaerus answered very neatly,

that he had not given his assent to the fact that they were pomegranates, but to the fact that it was

reasonable that they are pomegranates"

(Diogenes Laertius, Lives of the Philosophers VII.6.177).

The Stoic sage has no false beliefs, but he is not omniscient.

He does not always know what the future will bring or

even that the objects in the bowl in front of him are pomegranates. In some situations,

because he is not rash in his assent, he will

not assent to any of the impressions he gets about the matter he is considering

because none of them are cognitive.

In others,

as in the example, his only cognitive impression is not

that the objects in front of him are pomegranates but that it is reasonable that they are.

The Stoics understood "knowledge"

(ἐπιστήμη) to be assent reason cannot force us to withdraw. They

thought such assent is possible because there are cognitive impressions.

Assent to a cognitive impression issues in a κατάληψις. This word means "seizing" or "grasp." Because Cicero used cognitio to translate κατάληψις in the context of the Stoic theory of knowledge (Academica II.17), "cognition" is now a traditional translation for this grasp.

All cognitions are true because the propositional contents of all cognitive impressions are true, but not all cognitions are knowledge. Only the wise, according to the Stoics, have knowledge. Everyone else has "opinion" (δόξα). They took this to be what Socrates demonstrated.

Cicero, in the following describes how Zeno would explain assent, cognition, and knowledge:

"Zeno would spread out the fingers of one hand and display its open palm, saying 'An impression is like this.' Next he clenched his fingers a little and said, 'Assent is like this.' Then, pressing his fingers quite together, he made a fist, and said that this was a grasp and gave it the name κατάληψις. Then he brought his left hand against his right fist and gripped it tightly, and said that knowledge was like this and possessed by none except the wise man-but who is a wise man or ever has been even the Stoics do not usually say" (Academica II.145).

Just what Zeno had in mind is not all that clear, but part of the idea is that if our assents are to cognitive impressions, then a Socrates cannot use dialectic to make us withdraw them. We have grasped the truth, and our grip is too strong for a Socrates to pry open our hand.

We can get this kind of grip, the Stoics thought, if our assents are to cognitive impressions.

Cognitive Impressions are Clear and Distinct

The Stoics thought nature arranges things so that for what matters, we normally can put ourselves in a situation where the impressions we receive are cognitive impressions.

In situations in which we determine by looking whether something is true, sufficient light is necessary for us to make the determination correctly. When our minds are working normally and there is sufficient light, the impression we receive "bear[s] the impress and stamp" of reality in a certain way. It has a certain "clarity" and "distinctness," and nature arranges things so that when we have an impression with this character, its propositional content is true.

This Stoic view is a little hard to understand. Part of their idea is that every part of reality has a set of features that separates it from every other part. In a cognitive impression, these features make the impression "distinct" from impressions of other parts of reality. Cognitive impressions, further, are so "clear" that we naturally assent to them. We do not hold back because we think things might not be as they appear. We assent and get on with living our life.

Not all impressions are clear and distinct, but the Stoics thought that with practice we can learn to be careful with our assent so that we do not give it to noncognitive impressions. They thought that if we do that, because nature arranges for us to have cognitive impressions, our grip on reality is so strong no rational means can convince us to withdraw our assent.

We will think more about Stoic epistemology in the next lecture when we take up the Academic reaction to it. The Academics, as we will see, argued against the Stoic's epistemology.

The Stoic Theory of the Good Life

We can now begin to understand the Stoic good life and its connection to opinion and passion.

The Stoics thought that the good life is a matter of having knowledge of what is good and what is bad, but what they thought is good and is bad is not what we commonly think.

The Stoics understood the good in terms of the wisdom in nature.

They thought nature is completely and perfectly wise. They did not believe in a divine maker, as Plato did, but they thought that down to the smallest detail nature unfolds in a perfectly wise way. The Stoics thought that this wisdom in nature is the only good and the good life for a human being is the life in which we know and act according to this good.

At the same time, Stoics thought almost no one has knowledge of what is good and what is bad. When we acquire reason, we all form false beliefs about good and bad. We come to believe what human beings ordinarily believe: that health is good, sickness is bad, and so on.

In the language of Stoics, these false beliefs make us "fools."

"Zeno was the first (in his treatise On the Nature of Man) to

designate as the end 'life in agreement with nature' (or

'living agreeably to nature'), which is the same as a life according to

virtue, virtue being the goal towards which nature guides us. ... And this is

why the end may be defined as life in accordance with nature, or, in other

words, in accordance with our own human nature as well as that of the

universe, a life in which we refrain from every action forbidden by the law

common to all things, that is to say, the right reason which pervades all

things, and is identical with this Zeus, lord and ruler of all that is. And

this very thing constitutes the virtue of the happy man and the smooth current

of life, when all actions promote

the harmony of the destiny dwelling in the individual man with the

will of him who orders the universe"

(Diogenes Laertius,

Lives of the Philosophers VII.87).

"If a thing is considered a portent because it is seldom seen,

then a wise man is a portent; for, as I think, it oftener happens that a mule brings forth a colt than that nature

produces a wise man"

(Cicero, On Divination II.28.61).

"According to [the Stoics], ...

of men the greatest number are bad, or rather there are one or two whom they speak of as

having become good men as in a fable, a sort of incredible creature as it were and contrary

to nature and rarer than the Ethiopian phoenix; and the others are all wicked and are so

to an equal extent, so that there is no difference between one and another, and all who

are not wise are alike mad"

(Alexander of Aprodisias, De fato XXVIII).

(For the Ethiopian phoenix, see Herodotus, Histories II.73.1

and

Pliny the Elder, The Natural History X.2.)

"[I]n a manner this is philosophizing (φιλοσοφεῖν), to seek how it is

possible to employ desire and aversion without impediment"

(Epictetus, Discourses III.14.

10).

Epictetus is a late Stoic. He was born in Heirapolis (now in southwestern Turkey). He

seems to have been a slave by birth. At some point he was acquired by

Epaphroditus (himself an ex-slave influential in the rule of the emperors Nero (54-69

CE) and Domitian (81-96 CE)), who allowed him to study philosophy (while

still a slave) with the Stoic Musonius Rufus (30–101 CE).

Epaphroditus eventually freed Epictetus.

He then became a teacher in Rome. In 89, Domitian banished the philosophers.

Epictetus set up a school in Nicopolis in Epirus, in eastern Greece. He seems

to have remained there until his death in 135 BCE.

The "sage," in contrast to the fool, does not have these false beliefs.

He knows

that the good does not apply to the world insofar as he eats when he is

hungry, regains his health when he is sick, and generally gets the ends

he pursues.

So, because he does not attribute a

value to these things they do not possess, he

is not distressed if they are not part of his life.

The sage is not omniscient, but he knows that nature would not be showing wisdom if human beings generally did not eat when they were hungry, recover when they were ill, and so on. He knows, then, that it is reasonable to try to regain his health if he falls ill, but his impulse is not excessive because he does not attribute a value to his health it does not possess. Nor is he upset if he does not recover. He realizes that recovering in his circumstances is not part of the wisdom in nature and hence is not an outcome he has reason to pursue.

The Stoics thought the sage experiences a satisfaction the rest of us fools do not. We enslave ourselves with false beliefs about what is good and what is bad. Our lives as a result are filled with worry about whether we will get what we think is good and avoid what we think is bad, and we are distressed and unhappy when we fail to achieve or avoid these things.

When the fool assents to an impulsive impression, as he has false beliefs about what is good and what is bad, his assent issues in an "excessive impulse" (ὁρμὴ πλεονάζουσα).

To see this, suppose you get the impression that you are not going to recover from your illness. You find this impression extremely distressing if you wrongly believe that your death is bad. When you assent, your impulse is excessive. You struggle to regain your health and avoid your death, and you are filled with more and more fear as you see you are not succeeding.

This does not happen to the sage. His life is without such passions. He is ἀπαθής. Because he is not a fool, he does not have the experience of thinking something is good and not getting it. Neither does he have the experience of thinking something is bad and not avoiding it. Instead, because he is wise, the sage experiences complete and utter satisfaction in his life.

From the Stoic point of view, Socrates had this wisdom and satisfaction in his life. Given these passages from Plato's Phaedo, we can see why the Stoics thought this about Socrates:

"I had strange emotions when I was there. For I was not filled with pity as I might naturally be when present at the death of a friend; since he seemed to me to be happy (εὐδαίμων), both in his bearing and his words, he was meeting death so fearlessly and nobly" (Phaedo 58e).

"Up to that time most of us had been able to restrain our tears fairly well, but when we watched him drinking and saw that he had drunk the poison, we could do so no longer, but in spite of myself my tears rolled down in floods, so that I wrapped my face in my cloak and wept for myself; for it was not for him that I wept, but for my own misfortune in being deprived of such a friend. Crito had got up and gone away even before I did, because he could not restrain his tears. But Apollodorus, who had been weeping all the time before, then wailed aloud in his grief and made us all break down, except Socrates himself" (Phaedo 117c).

In this, although the Stoics conceive of the gods and the activity differently,

they follow the view in Plato and Aristotle that human happiness is god-like existence.

"We suppose the gods more than anyone are blessed and happy;

but what sorts of actions should we ascribe to them? Just actions? Surely they will

appear ridiculous making contracts, returning deposits, and so on. ... And when we

go through the possibilities, all such conduct appears trivial and unworthy of the gods.

We think, though, they are alive and active, since surely they are not

asleep like Endymion. And if someone is alive, and action is excluded, and

production [making things] even more, nothing is left but contemplation. Hence the activity of the gods superior in blessedness is

contemplation. And so the human activity most akin to this is the most conducive to happiness"

(Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics X.8.1178b)

Socrates, from the Stoic point of view, is living his life in accord with the good and wisdom of Zeus that "pervades all things"

(Diogenes Laertius,

Lives of the Philosophers VII.87).

We see, then, in the Stoics as in Plato and Aristotle before them, an interpretation of Socrates.

Perseus Digital Library:

Diogenes Laertius,

Lives of the Philosophers

Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon:

ἀπάθεια, apatheia, noun,

(ἀ "not" + πάθος, noun, páthos, "passion"), "without passion,"

"[The ruler in the just city] makes the least lament and bears it most mildly

when any such misfortune overtakes him"

(Republic III.387e).

The Platonic ideal is

μετριοπάθεια,

not ἀπάθεια.

δαιμόνιον, daimonion, noun, "divine"

ἐναργής , enargēs, adjective, "visible, palpable"

ἔννοια, ennoia, noun, "notion, conception"

εὐπάθεια, eupatheia, noun, "comfort, ease"

καταλαμβάνω, katalambanō, verb, "seize with the mind, comprehend"

καταληπτός, katalēptos, adjective, "capable of being seized"

κατάληψις, katalēpsis, noun, "seizing"

κατάληψις = κατά + λῆψις. κατά is a preposition (which, in κατάληψις, functions as an intensifying prefix).

The noun

λῆψις

("taking hold of, or seizing") comes from the verb

λαμβάνω

("to take hold of, grasp, or seize").

The parts of perceptio and comprehensio correspond to the parts of κατάληψις. per- and com- function

as intensifying prefixes deriving from prepositions. –ceptio and –prehensio denote the activity expressed by the verbs

capio

and

prehendo/prendo.

In this way, Cicero introduces perceptio and comprehensio as calques of κατάληψις.

The English 'calque' comes from the French calque.

ὁρμή, hormē, noun, "impulse," (Latin,

impetus)

πρόληψις, prolēpsis, noun, "preconception"

συγκατάθεσις, synkatathesis, noun, "assent"

Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary:

cognitio, noun, "cognition,"

comprehendo, verb, "to take, catch hold of, seize, grasp, apprehend, comprehend,"

comprehensibilis (also -dibilis), adjective, "that can be seized or laid hold of, comprehendible,"

Cicero uses comprehendibilis for καταληπτός. "'...[Zeno] termed

'graspable' (comprendibile)—will you endure these coinages?' 'Indeed

we will,' said Atticus, 'for how else could you express καταληπτόν'"

(Academica I.41).

comprehensio, noun, "a seizing or laying hold of with the hands"

impetus, noun, "impulse"

perceptio, noun, "a taking, receiving, a gathering in, collecting"

percipio, verb, "to take possession of, to seize, occupy"

perturbatio, noun, "confusion, disorder, disturbance"

ratio, noun, "a reckoning, account, calculation, computation"

scientia, noun, "knowledge"

visum, noun, "appearance, impression, presentation"

"[Zeno] made some new pronouncements about sensation itself, which he held to

be a combination of a sort of impact offered from outside (which he called

φαντασίαν and we may call a presentation (visum)..."

(Cicero, Academica I.40).

voluntarius, adjective, "willing"

Arizona State University Library. Loeb Classical Library:

Cicero,

On Ends,

On the Nature of the Gods. Academics

Diogenes Laertius,

Lives of the Philosophers VII.1 Zeno

"The Stoics revert to Socrates' extreme intellectualism. They deny an irrational

part of the soul. The soul is a mind or reason. Its contents are impressions or

thoughts, to which the mind gives assent or prefers to give assent. In giving

assent to an impression, we espouse a belief. Desires are just beliefs of a

certain kind, the product of our assent to a so-called impulsive impression"

(Michael Frede, "The Philosopher," 10.

Greek thought: A Guide to Classical Knowledge, 3-16).

"[T]he Stoic view seems to be that

[telling whether or not an impression is clear and

distinct] is a matter of practice and that in principle one can get so good at it that one

will never take a noncognitive impression to be cognitive"

(Michael Frede, "Stoics and Skeptics on Clear and Distinct Impressions," 169.

Essays in Ancient Philosophy, 201-222).

"[T]he Stoic sage does not gain his equanimity by shedding human concerns, but

by coming to realise what these concerns are meant to be, and hence what they

ought to be, namely the means by which nature maintains its natural, rational

order. And we have to realize that in this order our concerns play a very, very

subordinate role, and are easily overridden by more important considerations,

though we may find it difficult to accept this. But it does not follow from the

fact that they play a very subordinate role, that they play no role whatsoever.

Nature is provident down to the smallest detail. Hence it must be a caricature

of the wise man to think that he has become insensitive to human concerns and

only thus manages to achieve his equanimity. Things do move him, but not in such

a way as to disturb his balanced judgment and make him attribute an importance

to them which they do not have"

(Michael Frede, "The Stoic Affections of the Soul," 110.

The Norms of Nature: Studies in Hellenistic Ethics, 93-110).

"[E]ven the Stoic sage is not omniscient. He disposes of a general body of

knowledge in virtue of which he has a general understanding of the world. But

this knowledge does not put him into a position to know what he is supposed to

do in a concrete situation. It does not even allow him to know all the facts

which are relevant to a decision in a particular situation. He, for instance,

does not know whether the ship he considers embarking will reach its

destination. The Stoic emphasis on intention, as opposed to the outcome or the

consequences of an action, in part is due to the assumption that the outcome, as

opposed to the intention, is a matter of fate and hence not only not, or at

least not completely, under our control, but also, as a rule, unknown to us.

Therefore, even the perfect rationality of the sage is a rationality which

relies on experience and conjecture, and involves following what is reasonable

or probable. It is crucially a perfect rationality under partial ignorance"

(Michael Frede, "Introduction," 16-17.

Rationality in Greek Thought, 1-28).

"God constructs [human beings] in such a way that [when they become adults] they can recognize for themselves what

they need to do to maintain themselves (as long as they themselves are needed)

and hence will maintain themselves of their own choice and understanding. He

constructs them in such a way that they develop reason [as they become adults], and with reason an

understanding of the good, and thus come to be motivated to do of their own

accord what needs to be done. So, instead of constructing them in such a way

that they [like children and animals] are made to do what they need to do to maintain themselves, he

constructs them in such a way that they do this of their own initiative and

indeed can do it wisely, showing precisely the kind of wisdom, ingenuity,

resourcefulness, and creativity on a small scale, namely, the scale of their

life, which God displays on a large scale. In this way, if they are wise,

human beings genuinely contribute to the optimal order of the world, and they

find their fulfillment in this. This is what the good life for the Stoics

amounts to"

(Michael Frede, A Free Will.

Origins of the Notion in Ancient Thought, 73-74).

"Human life is a matter of banal things, getting up, eating, doing one's work,

getting married, having children, looking after one's family and one's

household, pursuing the concerns of one's community, being in practice

concerned with the well-being of other human beings. This is what life is

about. If there is something non-banal about it, it is the wisdom with which

these banal things are done, the understanding and the spirit from which they

are done"

(Michael Frede, "Euphrates of Tyre," 6.

Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies. Supplement, No. 68,

Aristotle After, 1997, 1-11).