Wisdom is a State of the Soul

Socrates Talked Strangely about the Soul

As we saw, to understand and evaluate what Socrates thought, we can expect Plato to work through several questions. A question we started to consider in the last lecture is how thinking in the "soul" (ψυχή) leads to action. We saw that Socrates thought that this thinking involves beliefs about what "we care for," but there is much more to the answer than that.

This more to the answer will take us to a theory of the mind historians call Socratic Intellectualism and to the theory they call Plato's Tripartite Theory of the Soul, but first we need to look backwards in Greek history to see how the Greeks thought about the soul.

Understanding Changed Over Time

Thinking must be a function of the soul if thinking in the soul causes action, but the Greeks did not always believe this about the soul. Their understanding changed over time.

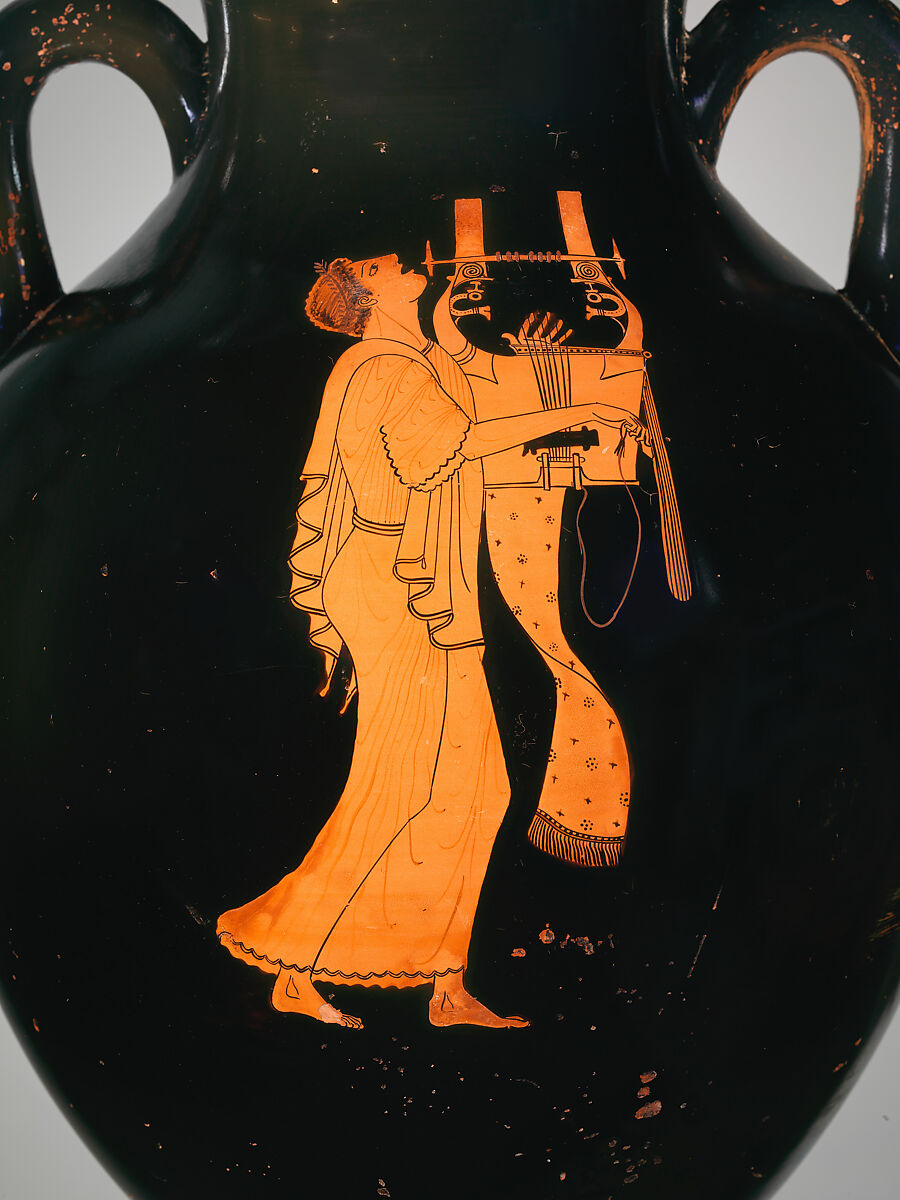

The earliest conception we

can see is in the Homeric poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey.

Many Greeks could quote Homer from memory.

Socrates, as Plato represents him, quotes Homer

at his trail (Apology 34d),

and this behavior was not restricted to those who moved in intellectual circles. The Greeks

knew the poems from the performances of rhapsodes, professional reciters who accompanied themselves

with the lyre.

Attributed to the Berlin Painter, c. 490 BCE

These poems were transmitted orally first. Then, in the late 8th or early 7th century BCE,

they were written down.

This was when writing in Greek was beginning to reestablish itself.

These poems were transmitted orally first. Then, in the late 8th or early 7th century BCE,

they were written down.

This was when writing in Greek was beginning to reestablish itself.

Other ways of thinking about the soul became important over time, but the conception in the Homeric poems remained common through the time of Socrates' death in 399 BCE.

The Soul and the Living

Before we consider the Homeric poems, we need to think about the word soul.

This word now has connotations we need to avoid if we are to understand the changes in how the Greeks thought about the soul. To accomplish this, it helps to approach this history with the assumption that having a ψυχή, or "soul," marks the difference between being alive and not being alive. Things with a soul are alive. Things without a soul are not alive.

This assumption about the soul is a basic meaning of ψυχή, and it is preserved in the contemporary use of the English verb animate to mean to bring to life. The etymology of this word goes back to the use of the Latin noun anima as a translation of ψυχή.

Given the assumption that the possession of a ψυχή marks the difference between being alive and not being alive, we can understand the historical changes in Greek thought about the soul as changes in beliefs about what the soul contributes to the life of living.

A Life Force that can Flit Away

.

In the Odyssey at

XI.74,

Odysseus meets the soul of Elpenor in Hades. Epenor had died (by falling from a roof and breaking his neck) but was not buried as custom demanded because there was no time. The soul of Elpenor

asks Odysseus to bury "him," where "him" refers

to his corpse.

"His flesh [Achilles's] too may be pierced with the sharp bronze, and in

him is but one life (ψυχή), and mortal do men deem him to be"

(Iliad XXI.568).

When the soul of Patroclus leaves him, Achilles describes what happens. "Alas," he says, "there

survives in the halls of Hades, a soul and a phantom (ψυχὴ καὶ εἴδωλον), with no wits (φρένες) at all"

(Iliad XXIII.103).

In the Odyssey at XI.222,

Odysseus's mother tells him that at death "the soul (ψυχὴ), like a dream, flits away...."

"Nay, seek not to speak soothingly to me of death, glorious Odysseus. I

should choose, so I might live on earth, to serve as the hireling of

another, of some portionless man whose livelihood was but small, rather than

to be lord over all the dead that have perished"

(Odyssey XI.489).

Socrates, in Plato's Phaedo, attributes this sort of

understanding of the soul to Crito.

"I cannot persuade Crito here that I am the Socrates who is now conversing

and arranging the details of his argument. He thinks I am the one

he will presently see as a corpse and he asks how to bury me"

(Phaedo 115c).

In the opening line of the

Iliad, Homer tells us that

Achilles's "wrath" caused the death of many Greeks. Their souls went to Hades,

and they were left on the battlefield.

"Sing, goddess, of the wrath of Peleus's son, Achilles, that destructive wrath of his that brought countless woes upon the Achaeans, and sent forth to Hades many valiant souls of heroes and made the heroes themselves spoil for dogs and every bird" (Iliad I.1).

(The Iliad purports to recount the final year of the ten-year siege of the city of Troy, which may have taken place in the 13th century BCE. The poem takes its title from a Greek name for Troy, Ἴλιον. Agamemnon leads the Achaeans. Achilles fights for Agamemnon.)

In this first line, we can easily understand part of what Homer is saying. Achilles acted on desires born in anger, and the actions he took led to the deaths of many men.

More difficult to understand is what Homer says happened when the men died.

Homer seems to be thinking of the soul as a life force that exists as some sort of residue of the living when the soul leaves the body in death. The presence of the soul marks the difference between being alive and being dead, but Homer does not think that something going on in the soul explains why the living human being acts the way he does. The soul is just a life force that manages to have an existence outside the body when the human being has died.

This can seem strange to us. We tend to use the word soul to talk about the person.

Psychological Explanations

This conception of the soul in the poems does not prevent Homer from giving what we would call psychological explanations of human behavior. It does, though, mean that the states and processes in these explanations are not states and processes of the Homeric soul.

These explanations, moreover, are not always ones we ourselves would give.

In the Iliad at

XIII.698,

when a blow

to the jaw dazes Euryalus, Homer describes him

as "other thinking"

"other thinking" (ἀλλοφρονέοντα)

and hence without the awareness of things people exhibit when

they are conscious.

We can translate Homer's words here, but it would be strange now to explain the behavior of someone

knocked unconscious by saying that he is "other thinking."

The same is true of Homer's explanation of what is going on in Odysseus's mind when he is deliberating about what to do in a certain situation he faces. We can see what experience Homer means to attribute to Odysseus, but we would not describe it as he does.

"Odysseus's spirit (θυμὸς) rose up in his chest, and he was anxious in his lungs and spirit, whether he should rush after them [the maids who consorted with the suitors who sought Penelope, Odysseus's wife, in Odysseus's absence] and deal death to each, or suffer them to lie with the insolent wooers for the last and latest time" (Odyssey 20.5).

Orphism and the Afterlife

In Orphism and Pythagoreanism, there is a different way of thinking about the soul. This thinking was initially in the minority, but it quickly became influential in philosophy.

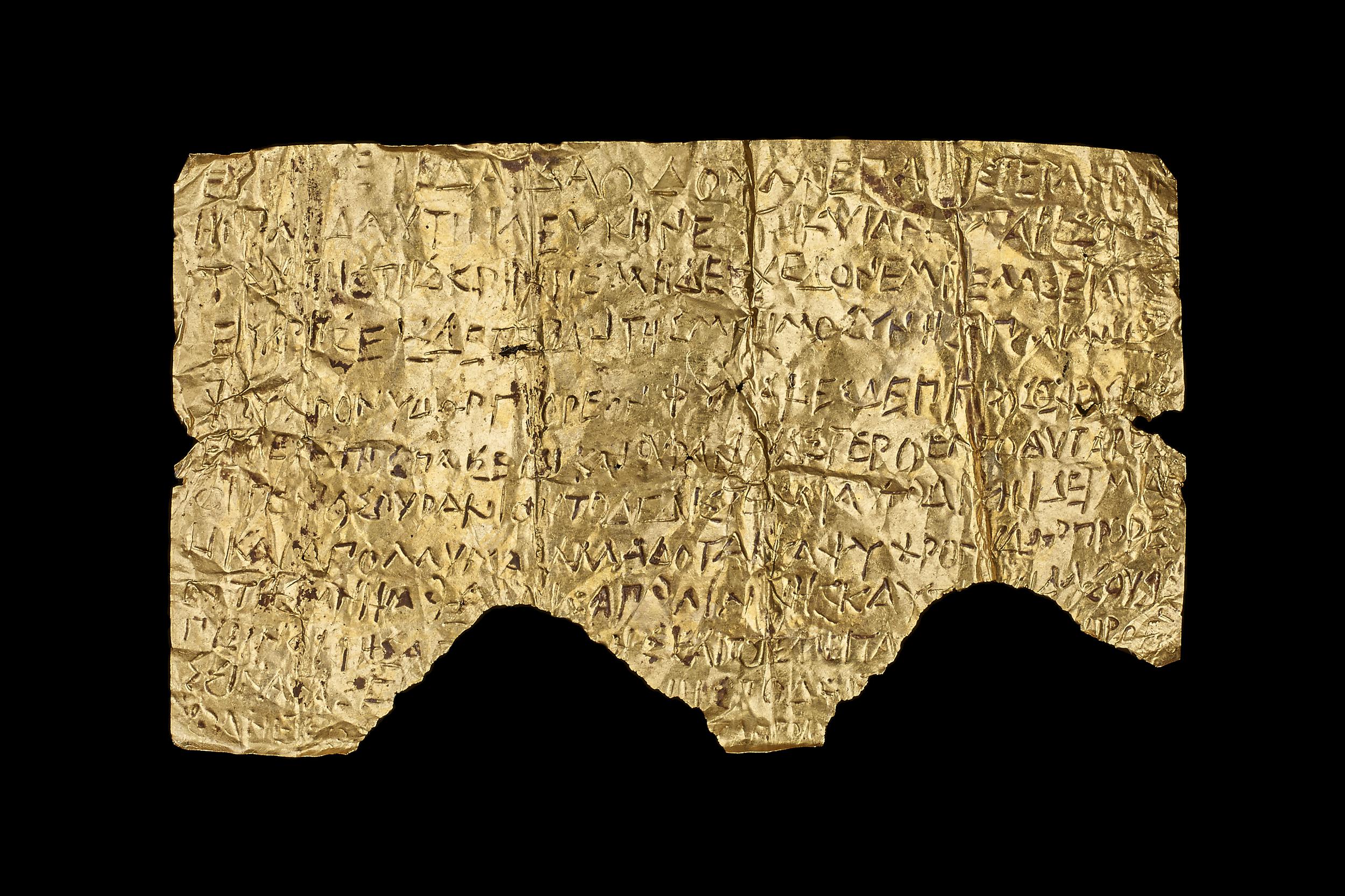

Orphic gold leaf, 4th century BCE.

British Museum 3155.

ΓΗΣΠΑΙΣΕΙΜΙΚΑΙΟΥΡΑΝΟΥΑΣΤΕΡΟΕΝΤΟΣΑΥΤΑΡΕΜ

ΟΙΓΕΝΟΣΟΥΡΑΝΙΟΝΤΟΔΕΔΙΣΤΕΚΑΙΑΥΤΟΙ

Γῆς παῖς εἰμι καὶ Οὐρανοῦ ἀστερόεντος, αὐτὰρ ἐμοὶ γένος οὐράνιον· τόδε δ’ ἴστε καὶ αὐτοί

We do not know much more about Orphism than that it involved purifying rituals.

The driving ideas remain unknown,

but they seem to have included the thought that we can look forward to our

existence in

the afterlife because it need not be grim, as it is in Homer.

Some evidence for this can be found in the fact that initiates were sometimes buried with gold leaves that carried inscriptions. In the British Museum, there is a leaf from the 4th century BCE with the following information: "I am a son of Earth and of starry Heaven, and so I have a heavenly origin; this you yourselves also know" (B 1.6-7 = DK 1 B 17.6-7).

About this afterlife, Plato seems to have thought the Orphics believed that the soul is in the body as a punishment and that when its sentenced is served, it might return home.

"I think it most likely that

those around Orpheus (οἱ ἀμφὶ Ὀρφέα) gave the body

its name, with the idea that

the soul is undergoing punishment, and that the body is

an enclosure to keep it safe, like a prison, and this is, as the name itself denotes,

the safe for the soul, until the penalty is paid, and not even a letter needs to be changed"

The Catylus is thought to be a middle dialogue.

"not even a letter needs to be changed." Socrates is saying that the word σῶμα

derives from the verb σῴζω.

(Cratylus 400b).

(Our knowledge of what the Orphics thought depends heavily on Plato. He refers to "books of Musaeus and Orpheus" (Republic II.364e), but these books are now lost.)

This conjecture in the Cratylus does not tell us what the soul contributes to the living. So, in this respect, we have not advanced much past the Homeric conception. What we can see, though, is the thought that souls somehow are what the living are. It is us who return home. We do not remain on the battlefield while our souls flit off to a grim existence in Hades.

This idea was new in Greek thought, and it would become important in philosophy.

Emotion and the Soul

The word 'character' is from

χαρακτήρ (charaktēr),

which means "stamping tool." Character, so to speak, stamps the flesh and blood to make an individual.

We get some of this new idea in more detail in

Herodotus (484–425 BCE) and Thucydides (460–400 BCE). They talk about

the soul in connection with emotions.

Herodotus tells the story of the Achaemenid king Cambyses who takes the Pharaoh Psammenitus prisoner and "makes a trial of his soul" by forcing him to watch as his daughter is enslaved and his son led away to be executed in a public spectacle (Histories III.14.1).

Herodotus, in a different context, comments that because of the forethought of god, animals good to eat and "timid in soul" are prolific breeders (Histories III.108.2).

We also see this way of thinking about the soul in Thucydides's report of Pericles's "Funeral Oration." This a speech Pericles gave in commemoration of the war dead at the end of the first year of the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BCE). He says that those who do not shrink from danger, even though they know very well the pain they may experience and pleasure they may miss, are "rightly judged strongest in soul" (History of the Peloponnesian War II.40.3).

Pythagoreanism and Transmigration

In the Pythagoreans, there was some more detailed analysis of what goes on in the soul.

Pythagoreanism

begins with Pythagoras.

He led a school in Croton (in Southern Italy) in about 530 BCE.

Xenophanes (6th to 5th century BCE) reports that Pythagoras once intervened when a puppy was being

whipped because he recognized the soul of a friend when it yelped

(DK B 21 7).

The behavior Pythagoras takes to indicate the soul of his friend

is not

intellectual.

In

Empedocles (5th century BCE) too, there is the idea that the soul is divine in

origin and that it

transmigrates as punishment.

"Of them, I too am now one, an exile from the divine and a wanderer"

(DK 31 B 115 = D 10).

Ps.-Iamblichus is a name historians use to refer to the author of Theology

of Arithmetic. The authorship of this work is disputed. Some historians

attribute it to Iamblichus (a 3rd to 4th century CE Platonist), but others

attribute it to a subsequent author who draws on Iamblichus.

Ps.-Iamblichus gives a report that suggests that

Philolaus (a Pythagorean and contemporary of Socrates) believed

the soul is responsible for emotion and

character but not for intelligence.

Ps.-Iamblichus reports that Philolaus said that "the head [is the place] of intelligence, that the heart [is the place] of the soul and sensation," that whereas "the brain is the ἀρχή or starting-point of a human being, the heart is the starting-point of an animal" (DK 44 B 13).

In this fragment, Philolaus does not pair the soul with "intelligence."

This way of thinking about the soul is consistent with the Pythagorean belief in transmigration. If the Pythagoreans thought that a human intelligence could migrate from a human being into a non-human animal, they would have to explain why this intelligence never shows itself. There is no such obstacle if character and thus the soul is what passes in transmigration.

Intellectualism about Character

Socrates' conception of the soul exists against this complex historical background.

If, for the moment, we set aside his view of the afterlife, we can see that what is

prominent in his conception is his understanding of character. Socrates understood the soul

so that it is responsible for character, and he understood character so that it

is part of intelligence.

"Then, Simmias, if this is true, my friend, I have great hopes that when I reach the place to

which I am going, I shall there, if anywhere, attain fully to that which has been my chief

object in my past life, so that the journey which is now imposed upon me is begun with good hope;

and the like hope exists for every man who thinks that his intelligence (διάνοιαν) has been purified and made ready.

Certainly, Socrates.

And does not the purification consist in this which has been mentioned long ago in our discourse,

in separating, so far as possible, the soul (ψυχὴν) from the body and teaching the soul the habit of

collecting and bringing itself together from all parts of the body, and living, so far as it can,

both now and hereafter, alone by itself, freed from the body as from fetters?

Absolutely"

(Phaedo 67b).

The evidence for this begins with Aristophanes (an Athenian comic playwright and older contemporary of Plato). In his comedy the Clouds, Aristophanes makes fun of Socrates and the new education that had become fashionable in 5th century Athens. This new education had become an object of suspicion because it was contrary to traditional thinking, and Socrates was caught up in the conservative reaction that would lead to his execution.

Socrates, in the Clouds,

heads what Aristophanes lampoons as a "thinkery."

When Pheidippides asks his father who dwells in the "thinkery" Socrates heads,

Strepsiades says he

does "not know the name accurately" and describes

them as "anxious thinkers, noble and excellent"

(Clouds 101).

The term "anxious thinker" is one Aristophanes invents.

Xenophon (contemporary with Plato),

reports that Socrates did not

participate in such "anxious thinking."

"He did not converse about the

nature of things in the way most of the others did-examining

what the sophists call the cosmos.... He

would argue that to trouble one's mind with such problems is

sheer folly"

(Memorabilia I.1.11).

Plato gives conflicting evidence.

In the Phaedo, which is a traditionally middle dialogue, Plato makes the character Socrates say that although in his youth

he "was tremendously eager for the kind of wisdom which they call inquiry about

nature (περὶ φύσεως ἱστορίαν)"

(96a),

he later lost interest in this inquiry.

In the Apology, Socrates say that the portrayal of him in Aristophanes's

Clouds has no truth in it.

"Many accusers have risen up against me before you,

who have been speaking for a long time,

many years already, and saying nothing true; and I fear them more

than Anytus and the rest, though these also are dangerous; but those

others are more dangerous, gentlemen, who gained your belief, since

they got hold of most of you in childhood, and accused me [as Aristophanes

portrays Socrates]

without any

truth, saying, There is a certain Socrates, a wise man, a ponderer

over the things in the air and one who has investigated

the things beneath the earth and who makes the weaker argument the

stronger"

(Apology 18b).

"Now let us take up from the beginning the question, what the accusation is from which the

false prejudice against me has arisen, in which

Meletus trusted when he brought this suit against me. What did those who aroused the prejudice

say to arouse it? I must, as it were, read their sworn statement as if they were plaintiffs:

Socrates is a criminal and a busybody, investigating the

things beneath the earth and in the heavens and making the weaker argument stronger and

teaching others these same things. Something of this sort is what they say. For you yourselves

saw these things in Aristophanes's comedy [the Clouds],

a Socrates being carried about there,

proclaiming that he was treading on air

and uttering a vast deal of other nonsense about which I know nothing"

(Apology 19a).

Strepsiades,

in conversation with his son, Pheidippides,

comically refers to its members as ψυχῶν σοφῶν

or "wise souls" who "in speaking of the heavens persuade people that it is an

oven, and that it encompasses us, and that we are the embers" and who "teach,

if one gives them money, to conquer in speaking, right or wrong

[by making one appear as the other]"

(94).

(We can see the complaints about higher education some people make are not new.)

This portrayal of Socrates in Aristophanes's Clouds does not show in detail how Socrates understood the soul. It is a comedy, not an analysis, but it does allow us to think that Socrates was known for talking about wisdom as a state of the soul as early as 423 BCE, the year the Clouds was first performed in the annual Dionysian festival in Athens.

Why Aristophanes's Portrayal is Funny

To understand what Socrates thought, it helps to think about the joke Aristophanes makes.

When Aristophanes calls Socrates and his followers "wise souls," he is being sarcastic. The majority in the audience found it funny to hear Socrates mocked in public in this way because they believed that he and his followers were absolute fools who lived contemptible lives.

Aristophanes trades on their beliefs by representing Socrates and his followers as devotees of the new scientific/sophistic education that had become an object of suspicion. Aristophanes depicts in comical fashion how the devotion to this new education has turned Socrates and his followers into "the pale-faced men with no shoes" who live strange ascetic lives. They have done something most in the audience would never do. They have traded their sense and vitality for the witless and feeble existence the audience associates with souls in Hades.

Many also in the audience would have found it laughably strange to hear that wisdom is a matter of the soul. The Homeric conception makes it a life force that continues to exist after death. On this view, our souls are not our minds. The newer conception we saw in Herodotus and Thucydides gets closer, but it does not make the soul responsible for anything specifically intellectual. Philolaus's theory emphasizes this point. Against this background, as the Clouds seems to report, Socrates would be comical not only for his ascetic life as the path to wisdom but also for his conception of the soul according to which it can become "wise."

Desires are Part of the Intellect

We do not know for sure how Socrates himself came to think that wisdom is a function of the soul, but we can imagine that what happened was something like the following.

The actions someone takes are the primary evidence for his character. Since no one acts without desire, his character explains the desires that motivate and move him.

In his analysis of what character is, Socrates took it to consist in beliefs about what is good and what is bad. We often appeal to these beliefs to explain why human beings act in the ways they do, and Socrates seems to have thought that explanations of any other kind are no more than rationalizations to shift responsibility from ourselves and from our beliefs.

This gives Socrates a conception of desire historians call "Socratic Intellectualism."

To know how to control our desires and hence our lives, we need to know how desires arise in the soul. Is there a basic power of desire we need to control to live beneficially? Or, alternatively, are our desires beliefs we form in an exercise of reason?

According to Socratic Intellectualism, desires are beliefs we form in an exercise of reason.

To live beneficially, we do not need to control a basic power of desire. There is no such power. Human beings do not work this way. Our desires are part of our intellect. They are beliefs about good and bad we form in an exercise of reason. We pursue what we believe is at least as good an outcome as any alternative available to us in the circumstances, and we calculate the value of outcomes in terms of our beliefs about what is good and what is bad.

The Many are Confused

Socrates, in Plato's Protagoras, has this understanding of how human beings

function.

In the Gorgias and the Meno, Plato can seem to make Socrates

think

that some desires are not beliefs.

The Protagoras is traditionally thought to be one of Plato's early dialogues. Socrates' primary interlocutor

is the Sophist, Protagoras.

At one point in their conversation, Socrates takes up the question of

what "rules" a human being. He suggests

"Come, Protagoras, and reveal this about your mind: What do you believe about

knowledge? Do you go along with the many? They think this way

about it, that it is not powerful, neither a leader nor a ruler (ἡγεμονικὸν οὐδ᾽ ἀρχικὸν),

that while knowledge is often present, what rules is something else, sometimes

desire, sometimes pleasure, sometimes pain, at other times love, often fear.

They think of knowledge as being dragged around by these other things, as if it

were a slave. Does the matter seem like that to you? Or does it seem to you that

knowledge is a fine thing and rules a man, so that if someone were to know what is

good and bad, he would not be forced by anything to act otherwise than knowledge

dictates, and that intelligence would be sufficient to save him?

Not only does it seem exactly as you say, but it would be shameful for me of

all people [because I call myself a Sophist and say I educate men]

to say that wisdom and knowledge are anything but the strongest in human

affairs"

(Protagoras 352a).

"Well is there something you call dread, or fear? And is it—I address myself to

you, Prodicus [a Sophist and contemporary of Socrates]—the same as I have in

mind—something I describe as an expectation (προσδοκίαν) of bad, whether you

call it fear or dread?

Protagoras and Hippias agreed to this description of dread or fear; but Prodicus

thought this was dread, not fear.

No matter, Prodicus. My point is this: if our former statements are

true, will any man wish to go after what he dreads, when he may pursue what he

does not? Surely this is impossible after what we have admitted—that he regards

as bad what he dreads? And what is regarded as bad is neither pursued

nor accepted willingly by anyone"

(Protagoras 358c).

"Each man possesses opinions about the future, which go by the general name of expectations; and of these, that

which precedes pain bears the special name of fear,

and that which precedes pleasure the special name of confidence;

and in addition to all these there is calculation, pronouncing which of them is good, which bad"

(Laws I.644c).

"Well now, Gorgias, a man who has learnt building is a builder, is he not?

Yes, Socrates.

And he who has learnt music, a musician?

Yes.

Then he who has learnt medicine is a medical man, and so on with the rest on the same principle; anyone who has learnt a

certain art has the qualification acquired by his particular knowledge?

Certainly.

So, on this principle, he who has learnt what is just is just?

Absolutely, I presume.

And the just man, I suppose, does what is just.

Yes, Socrates"

(Gorgias 460bb).

"Socrates thought all the virtues are knowledge, so that knowing

justice and being just go together, for as soon as we have learnt geometry or

building, we are builders and geometers"

(Aristotle, Eudemian Ethics I.1216b;

cf. Nicomachian Ethics 1144b).

to Protagoras that "knowledge" rules and that no

psychological state can move someone to act against his knowledge.

The argument is a little hard to see because the dramatic structure in the Protagoras is more complex than what we have seen in the dialogues we have considered so far.

Socrates takes "the many" (oἱ πολλοί) to deny that knowledge is a ruler and

"Simonides [of Ceos, lyric poet, c. 566-468 BCE] was not so ill-educated as to praise a person who

willingly did no bad, as though there were some who did bad willingly. I am fairly

sure of this--that none of the wise men considers that anybody ever willingly errs

or willingly does shameful and bad deeds; they are well aware that all who do shameful

and bad things do them unwillingly"

(Protagoras 345d).

"Then if the pleasant is good, no one who knows or believes

there are actions

better than those he is doing, and are possible, will do the lesser ones if he is

free to do the better ones; and this yielding to oneself is nothing but ignorance,

and mastery of oneself is as certainly wisdom.

They all agreed.

Well then, by ignorance do you mean having a false opinion and being

deceived about matters of importance?

They all agreed to this also.

Then no one willingly goes after bad or what he thinks to be bad;

it is not in human nature, apparently, to do so—to wish to

go after what one thinks is bad in preference to the good; and when compelled

to choose one of two bads, nobody will choose the greater when he may choose the lesser"

(Protagoras 358b).

to believe that

someone can know what is best but

be overcome by pleasure for something else.

The many, however, are not someone Socrates can question. They are just a way of talking about common belief. There is no one called the many who has these beliefs.

To get these common beliefs on the table, since he cannot proceed as we have seen him proceed in earlier dialogues, Socrates leads a conversation in which he and Protagoras identify what the many believe and how they would respond in dialectic. Protagoras, at the end of this conversation, accepts that the dialectic (he helps Socrates imagine) shows that the many have beliefs that commit them to denying it is possible for knowledge to be overcome by pleasure.

We can reconstruct how the dialectic shows this as follows.

The many, first of all, think that someone can be "overcomme by pleasure." They think the following is possible, even common, namely that someone can do something other than "what is best, even though [he] know[s] what it is and [is] able to do it" (Protagoras 352d).

These beliefs give Socrates the following premises to use against the many:

1. The best thing S can do is a (go to the gym).

2. S does b, where b (go to the party) ≠ a, because S is overcome by pleasure.

The many also believe (as Socrates works hard with Protagoras to get them to admit) that

PG. The pleasant is the good.

Since the question is whether "knowledge is a ruler" and hence whether S can be overcome by pleasure if he has knowledge, the assumption to be contradicted in the reductio is

3. S knows that the best thing he can do is a.

Further, since the many think that S need not be confused about what is best in the situation in which he is overcome by pleasure, the first inference is from this assumption to

4. S does not believe that doing b is as least as good as doing a.

Socrates now works to get the many to commit themselves to the negation of (4) and thus to contradict their claim that knowledge can be overcome by pleasure.

The argument Socrates uses to get the many to commit themselves to the negation of (4) is not straightforward to follow, but the crucial point seems to be that the many commit themselves to what Socrates himself believes about how human beings function. They assume that S must desire to do b if he does b, and Socrates shows them that they have beliefs that commit them to thinking that S has this desire only if S believes that doing b is as least as good as doing a.

What if anything does this show about what Socrates himself believes?

The rules of dialectic do not require Socrates to believe anything in particular. His role as questioner is to make the many contradict themselves, but given the context in which the dialectic takes place, it is natural to think the real target is Protagoras. By enlisting Protagoras to show the many that they are committed to thinking that what drives a human being are his beliefs about what is good and what is bad, Socrates is trying to get Protagoras to see that he too shares this belief about desire and how the human soul functions.

Socrates describes this belief they have uncovered as a fact about "human nature."

"Then [given what has been agreed,] no one willingly goes after bad or what he thinks to be bad; it is not in human nature (ἐν ἀνθρώπου φύσει), apparently, to do so—to wish to go after what one thinks is bad in preference to the good; and when compelled to choose one of two bads, nobody will choose the greater when he may choose the lesser" (Protagoras 358c).

We can see, then, that Socrates himself thought that human desire works this way and that the dialectic shows that Protaagoras and the many are committed to believing this too.

Looking Forward in the Platonic Dialogues

The question Plato now faces is whether Socrates was right about the soul and human nature.

As we will see in a subsequent lecture, Plato comes to believe that Socrates was wrong.

In the Republic (traditionally thought to be a middle dialogue), Plato concludes that the soul is more than reason, that it contains two nonrational parts in addition to reason, and that the desires in these parts are not beliefs about what is good and what is bad. Given this theory about how human beings function, it is possible for pleasure to overcome knowledge.

At this point, though, turning to this development now would put us ahead of ourselves.

Perseus Digital Library

Aristophanes, Clouds

(Loeb Classical Library:

Aristophanes, Clouds)

Strepsiades is burdened with debt because of his aristocratic wife and the

expensive tastes she encourages in their son, Pheidippides. So, in the scene below,

Strepsiades encourages his son to

enroll in the "thinkery" so that Socrates can teach him how to make

the weaker argument appear stronger. Strepsiades hopes

Pheidippides will use this skill to defeat the family's creditors in court.

Pheidippides, however, who is young and athletic, wants nothing to do with those

Aristophanes jokes about Socrates and his followers going without shoes at

Clouds 363,

719, and

858.

This was true of Socrates even in the coldest weather.

See Plato, Symposium 174a and

219a.

See also Xenophon, Memorabilia 1.6.2.

Chaerephon (Socrates's friend) was known for his pale, corpse-like appearance

(Clouds 503-504).

In (Birds 1555),

Aristophanes portrays Socrates as a

ψυχαγωγός

and Chaerephon as a "bat" from Hades who comes to drink

an offering of blood.

Many in his audience would have understood this against the background of Homer's

Odyssey XI.34

and

XXIV.14.

The verb corresponding to ψυχαγωγός can mean "lead or attract the souls of the living,

win over, persuade" or, negatively, "beguile," but the primary meaning is to

"lead departed souls to the underworld." So the joke in part is that Socrates' teaching

leads

his students to Hades.

At

Clouds 186, Strepsiades says that the students in the

thinkery look like "the men captured at Pylos."

In 425 BCE, the Athenians defeated

the Spartan force occupying Sphacteria (an island next to Pylos in the western Peloponnese).

They brought prisoners and held them in Athens

in chains

(Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War 4.41.1)

until peace was made. By the time the

Clouds was staged, they had been imprisoned for two years.

At Clouds 1112,

Strepsiades says that when his son graduates from the thinkery, he will

be "pale-faced and wretched."

Free women were expected to pale because they were expected to spend their time indoors. Free men,

by contrast, were expected to be deeply tanned because they were expected to spend the daylight

hours outdoors (on the farm if poor or in sport if rich, as Pheidippides with horses).

This is the context against which Socrates wryly says the following to

Hippocrates. "Protagoras, you see, Hippocrates, spends most of his time indoors"

(Protagoras 311a).

At Clouds 412,

the chorus tells Strepsiades that he will get the wisdom he desires if

"you have a good memory and are a ponderer, if there is endurance in

your soul, if neither standing nor walking tires you, if you are not too

put out by being cold or yearn for your breakfast, if you abstain from wine and

physical exercise and all other follies."

For more evidence of Socrates' ascetic way of life, see

Clouds 437 and

835.

In Xenophon, see

Memorabilia 1.3.5,

1.6.4,

1.6.6, and

2.1.1.

In

Plato, see Phaedo 64d.

"charlatans, the pale-faced men with no shoes, such as that

wretched Socrates and Chaerephon."

Strepsiades.

Do you see this little door and little house?

Pheidippides.

I see it. What then, pray, is this, father?

Strepsiades.

This is a thinkery (φροντιστήριον) of wise souls (ψυχῶν σοφῶν). There dwell

men who in speaking of the heavens persuade people that it is an oven, and that

it encompasses us, and that we are the embers. These men teach, if one give them

money, to conquer in speaking, right or wrong.

Pheidippides.

Who are they?

Strepsiades.

I do not know the name accurately. They are anxious thinkers

(μεριμνοφροντισταὶ), noble and excellent.

Pheidippides.

Bah! They are rogues; I know them. You mean the charlatans,

the pale-faced men with no shoes, such as that

wretched (κακοδαίμων) Socrates and Chaerephon

(Clouds 94).

Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott,

A Greek-English Lexicon

ἀμύητος, amyētos, adjective, "uninitiated, profane"

ἀκρατής,

(ἀ + κράτος), akratēs, adjective, "without strength"

ἑκών, hekōn, adjective, "of one's own accord"

ἡγεμονικός , hēgemonikos, adjective, "capable of command, authoritative"

εἴδωλον, noun, eidōlon, "phantom"

(a

φάντασμα,

an "appearance" of something)

In the

Odyssey XXIV.14,

the souls of the suitors (whom Odysseus has killed) fly like bats to the underworld

"where souls dwell, phantoms (εἴδωλα) of men who have done with toils."

θύμος, thymos, noun, "faculty of strong feeling and passion"

"little θυμὸς was in me"

(Illiad I.593).

"you do not do well to put this anger in your θυμῷ"

(Illiad VI.326).

"But when she revived, and her spirit (θυμὸς) was returned into her breast (φρένα)..."

(Illiad XX.475).

"But I took counsel how all might be the very best, if I might haply find some way of

escape from death for my comrades and for myself. And I wove all manner of wiles and

counsel, as a man will in a matter of life and death; for great was the evil that was

nigh us. And this seemed to my θυμὸν the best plan"

(Odyssey IX.420).

κακοδαίμων,

(κᾰκός

+

δαίμων), adjective, kakodaimōn, "unhappiness"

μεριμνοφροντιστής

(μεριμνάω

+

φροντιστής), merimnophrontistēs, noun, "one who is an anxious thinker"

παράδοξος, paradoxos, adjective, "contrary to expectation, incredible"

προσδοκίαν, prosdokian, noun, "expectation"

φαντάζω, phantazō, verb, "make visible, appears"

φάντασμα, phantasma, noun, "appearance"

Death makes the soul appear to the eye. The appearance is a "phantom," which

"flits away"

(Odyssey XI.222).

-μα is added to verbal stems to form nouns denoting the result,

a particular instance, or the object of an action

γράφω

("write") →

γράμμα

("that which is written")

φαντάζω ("appears, make visible") → φάντασμα ("appearance, vision")

φρήν, phrēn, noun, "seat of perception and thought" (located in the midriff)

"they may devise some other plan in their minds (φρεσὶ) better than this"

(Illiad IX.423).

"Patroclus, setting his foot upon Sarpedon's breast, drew the spear from out the flesh,

and the midriff (φρένες) followed therewith; and at the one moment he drew forth the

spear-point and the soul (ψυχήν) of Sarpedon"

(Illiad XVI.504).

φροντιστήριον, phrontistērion, noun, "place for meditation, thinking-shop"

σκιά, skia, noun, "shadow, shade of the dead, phantom"

"[C]ome to the house of Hades and dread Persephone, to seek soothsaying of the soul (ψυχῇ) of

Theban Teiresias, the blind seer,

Some of the religious specialists in antiquity:

μάντις

("seer" or "soothsayer")

ἀγύρτης

("beggar priest")

καθαρτής

("purifier"),

ὀνειροκρίτας ("interpreter of dreams")

ὀρνιθόσκοπος

("bird seer" or "augur")

Ὀρφεοτελεστής

("priest of the Orphic Mysteries")

χρησμολόγος ("dealer in oracles")

"Begging priests and soothsayers go to the doors of rich men and persuade them

that, through sacrifices and incantations, they have acquired a god-given power:

if the man or any of his ancestors has committed an injustice, they can fix it

with pleasant rituals. And if he wishes to injure an enemy, he will be able to harm a just

one or an unjust one alike at little cost, since by means of spells and enchantments

they can persuade the gods to do their bidding"

(Plato, Republic II.364b).

"[The superstitious

(δεισιδαίμων, "fearing the gods")]

will go to the interpreters of dreams,

the seers, the augurs, to ask them to what god or goddess he ought to pray.

Every month he will visit to the priests of the Orphic Mysteries"

(Theophrastus, Characters 16.11).

Theophrastus was the second head of Aristotle's Lyceum.

whose sense (φρένες) abides steadfast. To him even in death

Persephone has given mind (νόον), that he alone should have the sensibleness of the living (πεπνῦσθαι); but the others

flit about as shadows (σκιαὶ)"

(Odyssey X.490).

σῶμα

ψυχή, psychē, noun, "soul"

In HOmer, the ψυχή leaves temporarily during a faint

(Illiad XXII.467).

It appears at death

(Illiad IX.408,

XIV.518,

XVI.505,

XXII.362)

as it departs to "Hades"

(Odyssey XI.65),

where it exists as

"a phantom, with no mind [or: wits] at all"

(Illiad XXIII.104).

Hesiod does not talk much about the soul.

The word ψυχή does not appear in Theogony.

It appears once in

Works and Days 686, where it

means "life."

He does, though, talk about the afterlife without saying that it happens to the soul. He makes the

grimness of this afterlife

depend on one's conduct in life

(Works and Days,

109-210,

230-236,

276-278).

In the Shield of Heracles, the word appears three times. At

173, it means "life."

At

151

and

254, he says that the soul goes to Hades in death.

ψυχαγωγός, psychagōgos, adjective, "leading departed souls to the nether world"

"[H]istorically the decisive step was taken by Socrates in conceiving of human beings as

being run by a mind or reason.

And the evidence strongly suggests that Socrates did not take a notion of

reason which had been there all along and assume, more or less plausibly, that

reason as thus conceived, or as somewhat differently conceived, could fulfill

the role he envisaged for it, but that he postulated an entity whose precise

nature and function was then a matter of considerable philosophical debate,

and it was this entity that was the ancestor of our reason, rather than some

ability or part of us which had been acknowledge all along.

But however one thinks

of the matter and prefers to describe it, one can hardly want to doubt that Socrates'

assumption about the constitution of human beings constituted a crucial step in the history

of the notion of the mind and that for this step he could rely on antecedents. For it

seems clear enough that what Socrates actually did was to take

a substantial notion of the soul and then try to understand the

soul thus substantially conceived of as a mind or reason. By 'a

substantial notion of the soul' I do not mean the kind of insubstantial shadow

of a person presented at times in Homer, or some living-giving substance that

quickens the body, but a notion according to which the

soul accounts not only for a human being's being alive, but for its doing

whatever it does.... This was not a common conception, it seems, even in

Socrates' time, but it was widespread and familiar enough under the influence

of nontraditional religious beliefs, reflected, for instance, in

Pythagoreanism. And it seems to have been such a substantial notion of the

soul which Socrates took and interpreted as consisting in a mind or reason"

(Michael Frede, "Introduction," 18-19. Rationality in Greek Thought, 1-28.

Oxford University Press, 1996).

"[Socrates'] extreme intellectualism [about desire] seems to have been based on a conception of

the soul as a mind or reason, such that our desires turn out to be beliefs of a

certain kind"

(Michael Frede, "The Philosopher," 10. Greek thought: A Guide

to Classical Knowledge, 3-16. Harvard University Press, 2000).

"[I]n the Protagoras, [in his argument against how the many understand being overcome

by pleasure,]

Socrates seems to argue as if the soul just were

reason, and the passions were reasoned beliefs or judgments of some kind, and as

if, therefore, we were entirely guided or motivated by beliefs of one kind or

another. On this picture of the soul, it is easy to see why Socrates thinks that

nobody acts against his knowledge or even his beliefs: nothing apart from

beliefs could motivate such an action"

(Michael Frede, "Introduction," xxx. Plato. Protagoras, vii-xxxii).