Theories in the Middle Dialogues

Socrates Does More Than Ask Questions

Raphael's The School of Athens, 1509-1511,

fresco (Stanza della

Segnatura, Palazzi Pontifici, Vatican)

Plato points to the heavens and holds a copy of the Timaeus, a late

dialogue influential in the development of science.

In the Timaeus, Socrates and his interlocutors

have been in an extended discussion.

The previous day Socrates described "the best state and the character of

its citizens"

(Timaeus 17c).

Today it is time for Timaeus to speak. The parties to the discussion agree that he will begin with "the

origin of the cosmos and end with the nature of man"

(Timaeus 27a).

Plato's middle dialogues mark a new phase in his attempt to

understand Socrates.

The character Socrates still leads the conversations, but no longer does he primarily engage as a questioner in dialectic as he does in the Euthyphro and other early dialogues.

In the middle dialogues, Socrates introduces four Platonic theories:

• Theory of Recollection

• Theory of Forms

• Tripartite Theory of the Soul

• Theory of Justice

These theories, as they are traditionally called, are theories in the sense of the Ancient Greek noun θεωρία. This noun transliterates as theoria and means "a viewing or beholding." It describes the experience someone has as a spectator at the theatre or games.

In these theories, Plato is working through possible solutions to problems he uncovered in the early dialogues as he tried to understand what Socrates said and the unusual way he lived.

How We Acquire Virtue

In the Meno and the Phaedo, Socrates introduces the Theory of Recollection. This is the description historians use to refer to the theory. The character Socrates does not use it.

Meno opens the dialogue by asking Socrates about virtue.

"Can you tell me, Socrates, whether virtue (ἀρετή) can be taught? Or is it acquired by practice, not teaching? Or if it is acquired neither by practice nor by learning, can you tell me whether it comes to men by nature or in some other way" (Meno 70a).

These are important questions for Socrates, and we already know some about what the answers are supposed to be. Virtue is wisdom, and to become wise we need to engage in the sort of questioning we have seen in the Euthyphro and other early dialogues.

Plato knows this, but he wants a deeper understanding of what goes on in this questioning.

Socrates Plays the Respondent

To work toward this deeper understanding, Plato makes Socrates go back and forth between the roles of questioner and respondent in his conversation with Meno.

Socrates first tells Meno that he must be from a place where wisdom abounds because in Athens no one knows what virtue is, let alone how it is acquired. He says too that he shares in this lack of wisdom and has never come across anyone who knows what virtue is.

Meno does not take Socrates' reply seriously. He thinks Socrates must be exaggerating and surely he would have learned what

virtue is from Gorgias when he visited Athens.

Gorgias tells his audiences that there is no question

he can not answer

(Gorgias 447c).

This is both a play on the Theory of Recollection and an instance of Socratic

irony. Socrates never forgets any of the conversations he has about virtue. As we

saw in the Protagoras, he goes through them again and again.

Socrates pretends that he does not have a good memory and asks Meno to remind him what Gorgias said or to say himself what virtue is. Meno jumps at the chance to instruct Socrates, but he immediately runs into trouble. Rather than give an answer in the form Socrates wants, Meno says what virtue is in a man, a woman, and so on (Meno 71e). Socrates explains that he wants one answer that says what virtue is in all instances. Meno eventually manages to offer an answer in the right form, but now he has the problem we have seen in Socrates' other interlocutors. Meno is unable to defend his answer in subsequent questioning.

At this point, in frustration, Meno goes on the attack. He argues that Socrates' inquiry into virtue is impossible to complete. He argues that either the inquirer knows or does not know what virtue is and that in both cases he cannot inquire into what virtue is. If the inquirer does not know what virtue is, he will not recognize it even if he happens to come across it. If he knows what virtue is, he cannot inquire into what it is because he already knows what it is.

The Theory of Recollection

Socrates introduces the Theory of Recollection to show Meno that his argument is not sound.

"So that he who does not know about any matters, whatever they be,

may have true opinions on such matters, about which he knows nothing?

Apparently.

And at this moment those opinions have just been stirred up in him, like a

dream; but if he were repeatedly asked these same questions in a variety of forms,

you know he will have in the end as exact an understanding of them as anyone.

So it seems.

Without anyone having taught him, and only through questions put to him,

he will understand, recovering the knowledge out of himself?

Yes.

And is not this recovery of knowledge, in himself and by himself, recollection?

Certainly, Socrates"

(Meno 85c).

"When people are questioned, if you put the questions well, they answer correctly of

themselves about everything; and yet if they had not within them some knowledge and

right reason,

they could not do this"

(Phaedo 73a).

"We say there is such a thing as to be equal. I do not mean one piece of wood equal to another,

or one stone to another, or anything of that sort, but something beyond that--the equal itself (αὐτὸ τὸ ἴσον).

Shall we say there is such a thing, or not?

We shall say that there is most decidedly, Socrates.

And do we know it, the thing that is?

Certainly.

Whence did we come upon the knowledge of it? Was it not from the things

we were just speaking of, by seeing equal pieces of wood or stones or

other things, on the occasion of them that equal was in thought, it

being different from them? ... It is on the occasion of those equals, different as they are from that equal,

that you have thought and come upon knowledge of it?

That is perfectly true"

(Phaedo 74a).

"Then before we began to see or hear or use the other senses we must somewhere have gained a

knowledge of the equal itself, if we were to compare with it the equals which

we perceive by the senses, and see that all such things yearn to be like the equal itself

but fall short of it.

That follows necessarily from what we have said before, Socrates.

And we saw and heard and had the other senses as soon as we were born?

Certainly.

But, we say, we must have acquired a knowledge of equality before we had these senses?

Yes.

Then it appears that we must have acquired it before we were born.

It does.

Now if we had acquired that knowledge before we were born, and were born with it,

we knew before we were born and at the moment of birth not only

the equal and the greater and the less, but all things such as these? For our present argument is

no more concerned with the equal than with the beautiful itself

and the good and the just and the holy, and, in short, with all those things which

we stamp with the thing itself that is in our dialectic process of questions and answers;

so that we must necessarily have acquired knowledge of all these before our birth.

That is true, Socrates"

(Phaedo 75b).

Aristotle, as we will see, rejects the conclusion here that we "have acquired knowledge of all these before our birth." He agrees

with Plato that sense-experience alone is not enough to give us our concepts. Plato and Aristotle are both rationalists, but Aristotle

does not think, as Plato argues in the Phaedo, that the soul exists before its birth in the body.

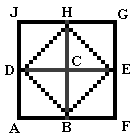

Socrates works through a construction that proves a theorem in geometry to demonstrate an instance of recollection.

He asks

one of Meno's slaves how to double the area of a square

(ABCD). The slave has not been taught geometry (and so has not been taught the

construction that shows that the square BEHD is double the area of the square

ABCD), but he finds his way to the answer in

the course of his conversation with Socrates. Socrates thinks this conversation shows that Meno can answer the what is virtue question.

He needs to engage in dialectic to rid himself of the false beliefs that make it hard for him to bring

to mind the correct answer he has possessed all along.

Socrates works through a construction that proves a theorem in geometry to demonstrate an instance of recollection.

He asks

one of Meno's slaves how to double the area of a square

(ABCD). The slave has not been taught geometry (and so has not been taught the

construction that shows that the square BEHD is double the area of the square

ABCD), but he finds his way to the answer in

the course of his conversation with Socrates. Socrates thinks this conversation shows that Meno can answer the what is virtue question.

He needs to engage in dialectic to rid himself of the false beliefs that make it hard for him to bring

to mind the correct answer he has possessed all along.

The Two Theses in the Theory

We can think of the Theory of Recollection as consisting in two theses.

The first thesis is the epistemological thesis.

This thesis is about the faculty of reason in the human soul. According to this thesis, reason includes true beliefs about consequence and incompatibility. These beliefs underlie the ability to make deductive inferences in reasoning. Meno's slave makes such inferences when he is thinking about the answers he gives to Socrates about how to double the square ABCD.

Reason, in this way, includes true beliefs on which reasoning depends.

The second thesis is the ontological thesis.

The thesis is about the existence of the soul. According to this thesis, the soul exists before entering the body and will continue to exist after death when it leaves the body.

The Epistemological Thesis

The epistemological thesis suggests the beginning of a solution to one of the puzzles about Socrates and his love of wisdom that emerges in the early dialogues.

Socrates, in these dialogues, shows that his interlocutors are confused about the virtues of character. He does not explain how they have become confused, but the idea seems to be that they have false beliefs that prevent them from seeing the correct answer.

This suggests that they have the correct answer and that it cannot be lost in questioning. In questioning, they abandon their false beliefs that prevent them from seeing the correct answer.

The Theory of Recollection suggests a way to begin to make sense of this idea.

Some true beliefs belong essentially to reason. They cannot be lost in questioning, but false beliefs acquired in experience can make these true beliefs hard to bring to mind.

What are these false beliefs that make the true beliefs hard to bring to mind?

They are beliefs we acquire when we are young. We get them from those who raise us and from the society in which we live. Euthyphro seems to rely on such beliefs when he says to Socrates that piety is "is doing what I am doing now, prosecuting the wrongdoer who commits murder or steals from the temples or does any such thing" (Euthyphro 5d).

What are the beliefs we cannot lose in dialectic because they are essential to reason?

They are the beliefs that constitute the concepts we possess as part of having reason.

Plato is working with the idea that to live the life it benefits us most to live, we must first engage in the love of wisdom to cleanse our minds. The thought is that we need to rebuild our life so that we start from the beliefs that constitute the concepts that are part of reason.

Virtues of Character

This answers some but not all the questions we had about the search for definitions.

The suggestion in the early dialogues is that definitions of the virtues of character differ only in their reference class. For piety, the reference class is the gods. For justice, it is human beings. Piety is what is appropriate with respect to the gods, justice is what is appropriate with respect to human beings, courage is what is appropriate in situations that inspire fear, and so on.

This means it is not enough to know that courage, for example, is what is appropriate in situations that inspire fear in those who are not wise. Even if this knowledge is in reason, we need to know what is appropriate in these situations if we are to have courage.

How do we get this knowledge?

The suggestion in the early dialogues is that we get this knowledge by knowing what is good and what is bad in the circumstances we face as we live our lives.

Eventually, then, if Plato continues to work through this line of thought, we can expect him to explain how knowledge of what is good and what is bad belongs to reason and how we apply this knowledge in the particular circumstances we face in living our lives.

The Ontological Thesis

The second thesis in the Theory of Recollection is the ontological thesis. This thesis is about the existence of the soul and the beliefs it forms because of its connection to the body.

Socrates thought that no one is born with the competency for living the most beneficial life. We have to acquire it, and the love of wisdom is the way we are to acquire it.

The Athenians, however, before Socrates came along, thought they were doing just fine. They did not think they needed to abandon the way they were living. Further, they found it difficult to think they should live like Socrates because they found his life so unappealing.

The ontological thesis, if it is true, helps explain why the Athenians think this way.

We Imprison Ourselves

Lovers of wisdom have discovered something about human beings.

They have realized, Socrates tells his interlocutors, that a "road (ἀταρπός) is leading us, together with our reason, astray in our inquiry [and attempt to possess wisdom], and that as long as we possess the body, and our soul is contaminated by such a bad as the body, we will never adequately gain what we desire-and that, we say, is truth" (Phaedo 66b).

This "road" is paved by false beliefs we acquire.

"The love of wisdom (φιλοσοφία) sees that the most dreadful thing about the imprisonment in the body is that it is caused by the lusts of the flesh, so that the prisoner is the chief assistant in his imprisonment. ... The soul of the true lover of wisdom ... abstains from pleasures and desires and pains and fears, so far as it can, reckoning that when one feels intense pleasure or fear, pain or desire, one incurs harm from them not merely to the extent that might be supposed—by being ill, for example, or spending money to satisfy one’s desires—but one incurs the greatest and most extreme of all evils. ... The evil is that the soul of every man, when intensely pleased or pained at something, is forced to suppose that whatever affects it in this way is most clear and real, when it is not so; and such objects are especially things seen... that in this experience the soul is most thoroughly bound fast by the body... that each pleasure and pain fastens it to the body with a sort of rivet, pins it there, and makes it corporeal, so that the soul takes for real whatever the body declares to be so. For because it has the same beliefs and enjoys the same things, the body it is compelled to the same ways and the same sustenance, and can never depart in purity to the other world, but must always go away contaminated with the body; and so it sinks quickly into another body again and grows into it, like seed that is sown. Therefore it has no part in the communion with the divine and pure and absolute. ... This, Cebes, is the reason why the true lovers of knowledge are temperate and brave .... For the soul of the lover of wisdom would not reason as others do, and would not think it right that the love of wisdom should set it free and that then when set free it should give itself again into bondage to pleasure and pain and engage in futile toil.... No, his soul believes that it must gain peace from these emotions, must follow reason and abide always in it, beholding that which is true and divine and not a matter of opinion, and making that its only food; and in this way it believes it must live, while life endures, and then at death pass on to that which is akin to itself and of like nature, and be free from human ills" (Phaedo 82e). When the soul enters the body, it goes on to live a life appropriate to the body because it has forgotten its interest in "truth." The soul fails to remember, and the body "fills us up with lusts and desires and fears and with all sorts of fancies and foolishness" (Phaedo 66b, 66c).

Socrates describes the lovers of wisdom as those who understand that "the body and its desires (τὸ σῶμα καὶ αἱ τούτου ἐπιθυμίαι)" (Phaedo 66c) are a problem we must overcome.

Because they understand their situation, the lovers of wisdom resolve not to "consort with or have dealings with the body other than what is absolutely necessary" and to "abstain from all bodily desires, and stand firm without surrendering to them" because they "believe that their actions must not oppose the love of wisdom" (Phaedo 67a, 82c, 82d).

Socrates describes life before the love of wisdom takes "possession of the soul" (Phaedo 82d) as a life in which the body has imprisoned the soul. He thinks further that the "ignorance" this imprisonment causes in the soul is reinforced through the satisfaction of "desire[s of the body], so that the captive himself" aids in the "imprisonment" of his soul (Phaedo 82e).

Socrates explains that "each pleasure and pain fastens the soul to the body with a sort of rivet, pins it there, and makes it corporeal, so that it takes for real whatever the body declares to be so." The soul does not see the world as it is. Instead, because it is imprisoned, it has "the same beliefs as the body and enjoys the same things" as the body (Phaedo 83d).

Escaping from the Prison

To change the way we live, we need to live ascetically. This is not much emphasized in the early dialogues, but the Phaedo portrays Socrates as thinking that dialectic is not enough.

Suppose, for example, that from experiences of eating sweets, someone gets the belief that eating them is good. Later he becomes aware of the arguments from medicine that this behavior is not healthy. Because he believes that his health is good, he resolves to stop eating sweets. This, though, does make him stop believing that eating them is good.

To abandon his belief, he needs to live ascetically to "unbind" himself from the way of living to which he became accustomed. He needs to practice not believing that eating sweets is good by resisting his urge to eat them. Over time, by engaging in this practice, he can reduce his liking for eating sweets and thus cause himself to stop believing that eating them is good.

The New Life We Want

This account of unbinding the soul from the body helps explain how we get rid of our false beliefs about what is good and what is bad, but it does not tell us what the true beliefs are.

Socrates explains that "the soul of every man, when intensely pleased or pained at something is forced to suppose that whatever affects it in this way is most clear and real, when it is not so; and such objects [that please or pain] are especially things seen" (Phaedo 83c).

Socrates thinks that we must liberate ourselves to know what is "most clear and real." We cannot see these things with our eyes. To know these things, we must use reason

We will think more in the next chapter about what Plato thinks we learn the world is like when we liberate ourselves from the false beliefs experience has given us.

In exploring this line of thought, we should keep in mind that Plato is going beyond anything the historical Socrates himself seems to have thought. Plato, in this way, gives us the first great interpretation of the project Socrates pioneered and took the initial steps. We will see others (in Aristotle and later in the Hellenistic philosophers), but Plato's is the most famous.

Perseus Digital Library:

Plato,

Meno,

Phaedo

Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott,

A Greek-English Lexicon:

ἀνάμνησις, anamnēsis, noun, "calling to mind"

ἐννοέω, ennoeō, verb, "reflect upon, consider"

ἐπιστήμη, epistēmē, noun, "knowledge"

ἐριστικός, eristikos, adjective, "involving a contest"

ὄντος (ontos) is a present participle of the verb

εἰμί,

"I am." The infinitive is εἶναι, "to be"

"Socrates' method of elenctic

dialectic turns on consistency as the crucial feature to be preserved. Not only

is inconsistency treated as a criterion for lack of knowledge or wisdom, it also

seems to be assumed that the progressive elimination of inconsistency will lead

to knowledge or wisdom. This presupposes that deep down we do have a basic

knowledge at least of what matters, that we are just very confused, because we

have also acquired lots of false beliefs incompatible with this basic knowledge.

I take it that in Plato this assumption at times takes the form of the doctrine

of recollection... . Unable to

get rid of these notions and the knowledge of the world they embody, the only

way to become consistent is to eliminate the false beliefs which stand in the

way of wisdom"

(Michael Frede, "On the Stoic Conception of the Good," 83.

Topics in Stoic Philosophy, ??-??. Oxford University Press, 1999).

"[Plato thinks] that a state of knowledge is the natural state of

reason, that what needs to be explained is not how it manages to acquire this

knowledge, but rather how and why it lost this natural state, [that is to say,]

how and why the knowledge it somehow has is latent, inoperative [in guiding the

way we live our lives]"

(Michael Frede, "Introduction," 14. Rationality in Greek Thought, 1-28. Oxford University Press, 1996).

"Plato, for instance in the Phaedo

[(75b)]

or in the

Timaeus

[(43a,

44a)],

suggests a view which would explain the state Socrates seems to presuppose [in

his questioning], namely a state in which in some

sense we confusedly already know the right answers to the important questions.

On this view, when reason or the soul, which pre-exists, enters the body upon

birth, it does so already disposing of the knowledge of the Forms, though it

gets confused by its union with the body, a confusion it only recovers from to

some degree mainly through sustained philosophical effort, recollecting the

truths it had known before entering the body. But it is only when it is

released from the body, freed from the disturbances involved in its union with

the body, and free to pursue its own concerns, rather than having to concern

itself with the needs of the body, or other concerns it only has made its own,

that it again has unhindered access to the truth"

(Michael Frede, "Introduction," 10. Rationality in Greek Thought, 1-28.

Oxford University Press, 1996).

"[R]eason, in the first instance, is not conceived of as an ability to reason,

to argue, to make inferences from what we perceive; it rather, in the first

instance, is conceived of as being a matter of having a certain basic

knowledge about the world, which then can serve as the starting point for

inferences. ... Thus, to be rational is not solely, and not even primarily, a

matter of being able to reason, to make inferences; it, to begin with, is a

matter of having the appropriate knowledge about the world. Correspondingly,

the perfection of reason does not consist primarily in one's becoming better

and better in one's ability to reason correctly; to be perfectly rational

rather is to be wise..., and this involves, first of all, an articulate

understanding of, or knowledge about, the world"

(Michael Frede, "The Stoic Conception of Reason," 54. Hellenistic Philosophy:

Volume II, 50-63. Athens: International Center for Greek Philosophy, 1994).