The Tripartite Theory of the Soul

Desire in the Three Parts of the Soul

The parts of the soul are "powers" or "faculties."

The Latin

facultas is a translation of the

Greek

δύναμις.

Aristotle has

a version of the tripartite theory. The Platonists and Aristotelians in later anquity

also have a version.

In Socratic Intellectualism and the Tripartite theory,

rational does not mean reasonable.

The thinking in reason

can be reasonable or unreasonable, but it is rational by definition.

It is thinking that belongs to reason. In these theories, rational

is descriptive and reasonable is normative.

In the Republic, Plato has Socrates argue that the soul is tripartite. This theory

of the soul, like the one Socrates expresses in the Protagoras,

is a theory about the human mind.

The Three Parts of the Soul

According to the Tripartite theory, reason is not the only power of the mind. In addition to this rational part, the soul has nonrational parts. They are spirit and appetite.

- reason, τὸ λογιστικὸν

- spirit, τὸ θυμοειδές

- appetite, τὸ ἐπιθυμητικόν

To understand the Tripartite Theory as a way of thinking about human beings, it is necessary to understand what is supposed to be true of a human being if his soul has these three parts.

Rational and Nonrational Desire

A human being whose soul has these parts has desires. The desires of reason are his rational desires. The desires of appetite and spirit are his nonrational desires.

This is not the understanding of desire we saw in Socratic Intellectualism.

According to Socratic Intellectualism, there are no nonrational desires because the soul does not have nonrational parts. This does not mean all desires are reasonable. All desires are beliefs about what is good and what is bad, and these beliefs need not be reasonable.

The nonrational desires in the Tripartite theory (the desires of the nonrational parts of the soul) are beliefs, but these beliefs are not about what is good and what is bad.

It follows that the Tripartite Theory is inconsistent with Socratic Intellectualism.

The Parts of the Soul can Conflict

"If the pleasant is good, no one who has knowledge or thought of other actions as

better and as possible for him to do, will do as he proposes if he is free to do

the better ones; and this yielding to oneself is nothing but ignorance, and

mastery of oneself is wisdom"

(Protagoras 358b).

"this yielding to oneself is nothing but ignorance"

Someone might say that although he does y, he knows x is better. The facts, though,

according to Socrates, are different. His state of mind is ignorance, not knowledge.

An example helps show what Socrates means.

From my experiences of eating sweets,

I develop the belief that eating them is good. Later I become aware of the arguments

from medicine that this behavior is not healthy. I believe that my health is good. So

I resolve to stop eating sweets, but this itself does not cause me to stop believing

that eating them is good. When I act on this belief, it can be tempting to explain what

happened by saying that I know that eating sweets is bad but do it anyway because I

am overcome by pleasure. Socrates rejects this explanation. He thinks that I do not know

that eating sweets is bad as long as I continue to believe that eating them is good.

"The body fills us with passions and desires and fears, and all sorts of

fancies and foolishness"

(Phaedo 66c).

The Tripartite theory has consequences for whether pleasure can overcome knowledge.

Socrates, in the Protagoras, as we have seen, argues that pleasure cannot overcome knowledge. In the experience we describe as being overcome by pleasure, what really happens is that we act on a belief we have trouble abandoning because we are not "masters of ourselves."

In the Republic, Socrates understands what happens in the experience of being overcome by pleasure as a failure of reason to rule. Reason is the "naturally better part" and should rule, but the two nonrational parts can have desires that conflict with the desires in reason.

"Yet is not the expression mastery of oneself ridiculous? He who

is stronger than himself would also presumably be weaker than himself, and he who is

weaker than himself, stronger, since the same person is induced by all these expressions.

Of course, Socrates.

Nonetheless, the expression seems to

me to mean that, in the soul there is a better part and a worse part and

that, whenever the naturally better part is in control of the worse, this is

expressed with the words mastery of oneself. This, at any rate, is a term of praise. But when the smaller and better part is

overpowered by the larger part, because of bad upbringing and certain company,

this is called yielding to one's self"

(Republic IV.430e).

If the Tripartite Theory is true, it is possible to know that something is best but do something else because a desire in the "worse part" of the soul overpowers the desire in reason.

An Argument from Opposites

"It is obvious the same thing will never do or suffer

opposites in the same respect in relation to the same thing and at the same

time. So if ever we find this happening we shall know that it was not the

same thing but a plurality"

(Republic IV.436b).

"Now, wouldn’t you consider assent and dissent, wanting to

have something and rejecting it, taking something and pushing it way, as all

being pairs of mutual opposites—whether of opposite doings or of opposite

undergoings does not matter?

Yes, they are opposites.

What about thirst, hunger, and the appetites as a whole, and

also willing and wishing? Would you include all of them somewhere among

the kinds of things we just mentioned? For example, wouldn’t you say that

the soul of someone who has an appetite wants the thing for which it has

an appetite, and draws toward itself what it wishes to have; and, in addition,

that insofar as his soul wills something to be given to it, it nods assent to

itself as if in answer to a question, and strives toward its attainment?

I would"

(Republic IV.437b).

"Thirst itself is in its nature only for drink itself.

Absolutely.

So the soul of the thirsty person, insofar as he is thirsty, does not

wish anything else but to drink, and it wants this and is impelled toward it.

Clearly"

(Republic IV.439b).

"Are we to say that some men sometimes though thirsty refuse to drink?

We are indeed, many and often.

What then, should one affirm about them? Is it not that there is something in

the soul that bids them to drink and a something that forbids, a different

something that masters (κρατοῦν) that which bids?

I think so.

And is it not the fact that that which inhibits such actions arises when it

arises from the calculations of reason (λογισμοῦ), but the impulses which draw

and drag come through affections and diseases?

Apparently.

Not unreasonably, shall we claim that they are two and different from one

another, naming that in the soul whereby it reckons and reasons the reasoning

part (λογιστικὸν) and that with which it loves, hungers, thirsts, and gets

passionately excited by other desires, the unreasoning (ἀλόγιστόν) and

appetitive part (ἐπιθυμητικόν)—companion of various repletions and

pleasures.

It would not be unreasonable but quite natural, Socrates"

(Republic IV.439c).

Cf. Phaedo 94b.

"Of the spirit (θυμοῦ), that with which we feel anger (θυμούμεθα), is it a

third, or would it be the same as these [we have distinguished]?

Perhaps with one of these, the appetitive.

But I once heard a story which I believe, that Leontius the son of Aglaion, on

his way up from the Peiraeus under the outer side of the northern wall, becoming

aware of dead bodies that lay at the place of public execution

knew a desire to see them

and at the same time was disgusted and turned away. For a time he

struggled and veiled his head, but finally, overpowered (κρατούμενος)

by his

desire,

he pushed his eyes wide open, rushed up to the corpses, and

cried, 'There, you

wretches, take your fill of the fine spectacle!'

I too have heard the story.

Yet, surely, this anecdote signifies that anger sometimes

fights against desires, as one thing against another.

Yes, it does, Socrates"

(Republic IV.439e).

"And don’t we often notice on other occasions that when

desires force (βιάζωνταί) someone contrary to his rational calculation, he reproaches

himself and feels anger at the thing in him that is doing the forcing; and just

as if there were two warring factions, such a person’s spirit becomes the ally

of his reason? But spirit partnering with appetite to do what reason has

decided should not be done—I do not imagine you would say that you had

ever seen that, in yourself or in anyone else.

No, by Zeus, I would not"

(Republic IV.440a).

"So in the soul, there is the spirited part (θυμοειδές), which is the helper of

reason by nature unless it is corrupted by bad nurture?

We have to assume it as a third, Socrates.

Yes, provided it shall have been shown to be something different from the rational,

as it has been shown to be other than the appetitive.

That is not hard to be shown, Socrates. For that much one can see in children,

that they are from their birth full of rage and high spirit, but as

for reason, some of them, to my thinking, never participate in it, and the

majority quite late.

Yes, by heaven, excellently said, and further, one could see in animals

that what you say is true"

(Republic IV.441a).

"The same magnitude, I presume, viewed from near and from far does not

appear equal.

Why, no.

And the same things appear bent and straight to those who view them in water

and out, or concave and convex, owing to similar errors of vision about colors,

and there is obviously every confusion of this sort in our souls. And so

scene-painting in its exploitation of this weakness of our nature falls nothing

short of witchcraft, and so do jugglery and many other such contrivances.

True.

And have not measuring and numbering and weighing proved to be most gracious aids to

prevent the domination in our soul of the apparently greater or less or more or heavier,

and to give the control to that which has reckoned and numbered or even weighed?

Certainly.

But this surely would be the function of the part of the soul that reasons and

calculates (λογιστικοῦ).

Why, yes, of that.

And sometimes, when this has measured and declares that certain things are larger or

that some are smaller than the others or equal,

the opposite appears (φαίνεται) at the same time.

Yes.

And did we not say it is

impossible for the same thing at one time to believe (δοξάζειν) opposites about the same thing?

And we were right in affirming that.

The part of the soul, then,

that opines (δοξάζον) in contradiction of measurement could not be the same with that which

conforms to it.

Why, no.

Further, that which puts its trust in measurement and

reckoning must be the best part of the soul.

Surely.

That which opposes it

must belong to the inferior parts of the soul.

Necessarily.

This, then, was what I meant when I said that poetry, and

in general the mimetic art, produces a product that is far removed from truth in

the accomplishment of its task, and associates with the part in us that is

remote from intelligence (φρονήσεως), and is its companion and friend for no

sound and true purpose"

(Republic X.602c).

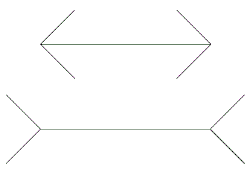

The Müller-Lyer Illusion.

The second horizontal line appears longer than than the first, but in fact the

two lines are the same in length.

Socrates appeals to familiar situations to show that the soul is tripartite.

Socrates appeals to familiar situations to show that the soul is tripartite.

In the first, someone is thirsty but refuses to drink. In situations of this sort, Socrates thinks that there are opposite desires: a desire to drink and a desire not to drink. Socrates thinks that because these desires move us in opposite ways, they must belong to different parts of the soul. He thinks that the soul moves the body and can simultaneously move it in opposite ways only if one part is moving it in one way and another part is moving it in the other way.

In addition to appetite and reason, Socrates believes that the soul has a third part.

Socrates appeals to a story about Leontius to show that anger sometimes conflicts with the appetitive part of the soul. If this anger is not a matter of reason, it must belong to a third part of the soul. To show that anger like Leontius experienced is not a matter of reason, Glaucon supplies the argument. He says that "some [children]... never participate in [reason], and the majority quite late." So, since children get angry about their appetitive desires, and reason does not play a controlling role in their behavior, spirit is the third part in the soul.

The desires in the three parts of the soul are for different things.

Appetite has desires by having beliefs about what brings pleasure and pain to the body. Spirit has desires by having beliefs about what brings honor and shame, and reason has desires by having beliefs about what is good and beneficial and what is bad and harmful.

Another Argument for Reason

Socrates later gives another example to show that reason is one of the parts of the soul.

He says that sometimes when reason "has measured and declares that certain things are larger or that some are smaller than the others or equal, the opposite appears at the same time."

To begin to see what Socrates has in mind, suppose that lines are arranged in an Müller-Lyer Illusion so that one appears to us longer than the other. In this situation, even after measurement reveals to us that the lines are equal in length, the appearance that they are unequal persists because the arrangement of the lines tricks our eyes.

In this situation, Socrates thinks the soul assents and dissents. It assents to the impression that the lines are the same length because this is how they continue to appear, and it dissents to this impression because measurement has shown they have different lengths. Because assent and dissent are opposites, Socrates concludes that this occurs in different parts of the soul.

In his argument, Socrates attributes "beliefs" (δόξαι) to the nonrational parts of the soul and talks about the part that "opines in contradiction of measurement" (Republic X.603a).

This helps us begin to see what the beliefs are like in the nonrational parts. The thought seems to be that these beliefs are representations produced by the senses, memory, and imagination, not by measurement, questioning, and other instances of the thinking in reason.

Reason Should Rule the Soul

Different organizations of the parts of the soul are possible. Socrates thinks that in the proper organization, reason knows and rules, spirit is reason's ally, and appetite is under control.

"Does it not belong to the reasoning part to rule,

since it is wise and exercises foresight on behalf of

the whole soul, and for the spirited part to obey and be its

ally?

Assuredly, Socrates"

(Republic IV.441e).

There are questions about the details of this and the other possible organizations of the soul.

One is about how a part of the soul comes to rule.

In Socrates' initial example, "some men sometimes though thirsty refuse to drink." The men in this example do not drink, but the appetite in their souls "bids" them to drink.

Why does this "bidding" not result in drinking?

We cannot just say that the "bidding" does not result in drinking because reason "forbids" it. This does not explain why the "forbidding" wins out over the "bidding."

An alternative is to say that the winning desire is the desire from the part of the soul that rules. When reason rules, the "forbidding" in reason wins over the "bidding" in appetite. When appetite rules, the "bidding" wins in appetite wins over the "forbidding" in reason.

Now we need to know how a part comes to be in control and thus to rule in the soul.

Training Appetite and Spirit

"[I]n children the first childish sensations are pleasure and pain,

and that it is in these first that virtue and vice come to the soul;

but as to wisdom and settled true opinions, a man is lucky if they come to him

even in old age and; he that is possessed of these blessings, and all that

they comprise, is indeed a perfect man. I term education, then, that in

which virtue first

comes to

children. When pleasure and love, and pain and hatred, spring up rightly in the souls

of those who are unable as yet to grasp the reason; and when, after grasping

reason, they consent thereunto that they have been rightly trained in

fitting practices:—this consent, viewed as a whole, is virtue, while the part of it

that is rightly trained in respect of pleasures and pains, so as to hate what ought to be

hated, right from the beginning up to the very end, and to love what ought to be

loved, if you were to mark this part off in your account and call it education,

you would be giving it, in my opinion, its right name"

(Laws II.653a).

Cf. Laws II.659d;

Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics II.3.1104b.

The explanation Socrates gives involves a process of education he describes.

One of the aims of this education is to train the appetitive and spirited parts so that they exist in harmony with reason and its beliefs about what is good and what is bad.

Because the young are "especially malleable and best take on whatever pattern one wishes to impress on" them, Socrates thinks that they are not "to hear any old stories made up by just anyone, and [in this way] to take beliefs into their souls that are, for the most part, the opposite of the ones we think they should hold when they are grown up" (Republic II.377b). Further, because first impressions in children are hard to change, he thinks that "the first stories they hear about virtue should be the right ones for them to hear" (Republic II.378e).

Stories about virtue mould the spirited part of the soul to like and dislike the appropriate things. Together with training for the appetite, this ensures that reason is the ruler.

"Since [the correctly educated] feels distaste correctly, he will praise fine things, be pleased by them, take them into his soul, and, through being nourished by them, become fine and good. The ugly or shameful, he will condemn and hate while he is still young, before he can grasp the reason. Because he has been so trained, he will welcome the reason when it comes and recognize it easily because of its kinship with himself" (Republic III.401e).

Knowledge is Not Enough

According to the Tripartite Theory, although reason can rule, Socrates was wrong about how powerful knowledge is. He thought knowledge could not be "dragged around."

"What, Protagoras, do you believe about

knowledge? Do you go along with the many? They think this way

about it, that it is not powerful, neither a leader nor a ruler,

that while knowledge is often present, what rules is something else, sometimes

desire, sometimes pleasure, sometimes pain, at other times love, often fear.

They think of knowledge as being dragged around by these other things, as if it

were a slave. Does the matter seem like that to you? Or does it seem to you that

knowledge is a fine thing and what rules a man, so that if someone were to know what is

good and bad, he would not be forced by anything to act otherwise than knowledge

dictates, and that intelligence would be sufficient to save him?

Not only does it seem exactly as you say, Socrates, but it would be shameful for me of

all people [because I call myself a Sophist and say I educate men]

to say that wisdom and knowledge are anything but the strongest in human

affairs"

(Protagoras 352a).

If the Tripartite Theory of the Soul is true, the view Socrates expresses in the Protagoras is false: knowledge of what is good and what is bad is not "sufficient to save [a man]."

As we will see in the next lectures, Plato thinks that justice is what "saves [a man]." Wisdom is necessary, but unless the soul is just, knowledge can be overcome by pleasure.

Perseus Digital Library

Plato's

Republic,

Theaetetus,

Timaeus,

Philebus

Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott,

A Greek-English Lexicon

βούλησις, boulēsis, noun, "willing"

επιθυμία, epithymia, noun, "appetite"

ἐπιθυμητικός, epithymētikos, adjective, "desiring, coveting, lusting after"

Plato uses ἐπιθυμητικός and θυμοειδής as adjectives corresponding to the

επιθυμία and the θυμός.

θυμοειδής, thymoeidēs, adjective, "high-spirited"

θυμός, thymos, noun, "strong feeling or passion"

λογιστικός, logistikos, adjective, "skilled or practiced in cacluating"

μουσική, mousikē, noun, "art over which the Muses preside"

ὄρεξις, orexis, noun, "appetency, conation, including ἐπιθυμία, θυμός, βούλησις"

πρόνοια, pronoia, noun, "foresight"

"Socrates thought that

there is no such thing as acting against one's own better judgment. ...

Plato, Aristotle, and their followers, on the other hand, believed that

such cases could not be explained as purely intellectual failures, that one

had to assume that besides reason there is an irrational [= nonrational] part of the soul with

its own needs and demands which may conflict with the demands of reason and

which may move us to act against the dictates of reason, if reason has not

managed to bring the irrational part of the soul firmly under its control"

(Michael Frede, "The Stoic Doctrine of the Affections of the Soul," 96.

Norms of Nature: Studies in Hellenistic Ethics, 93-100. Cambridge University

Press, 1986).

"[I]t is not the task of reason to provide us only with the appropriate knowledge and

understanding; it is also its task to provide us with the appropriate desires. To act

virtuously [for Aristotle] is to act from choice, and to act from choice is to act on a desire of reason.

The cognitive and the desiderative or conative aspects of reason are so intimately linked

that we may wonder whether in fact we should distinguish, as I did earlier, between the

belief of reason that it is a good thing to act in a certain way and the desire of reason

which this belief gives rise to, or whether, instead, we should not just say that we are

motivated by the belief that it is a good thing to act in this way, recognizing this as a

special kind of belief which can motivate us, just as the Stoics think that desires are

nothing but a special kind of belief"

(Michael Frede, A Free Will. Origins of the Notion in Ancient Thought, 49-51.

University of California Press, 2011).