JUSTICE AND THE GOOD LIFE

The Opening Conversation and the Challenge

A πόλις or "city" (or "city-state" in some translations) is an ancient political system

for group living that consisted in a ruling center and surrounding territory.

In the 5th century BCE, there were about 1500 such cities scattered throughout

the Mediterranean and Black Sea regions. Rarely did their territories

exceed a hundred square miles or their citizens number more than a few thousand.

Their

economies were mostly agricultural.

Athens was an exception. It was unusually large and urban.

The Piraeus

is the Athenian port on the Phaleron Bay, about five miles southwest of Athens.

The conversation in the Republic takes place in Polemarchus's house in

the Piraeus

(Republic I.327a, I.328b).

Republic I.327a-328c. The opening scene.

Republic I.328c-331d. Socrates talks with Cephalus.

Republic I.331d-336b. Socrates talks with Polemarchus.

Republic I.336b-354b. Socrates talks with Thrasymachus.

Republic I.354b-354c. The conversation ends in perplexity.

Republic II.357a-358e. Glaucon challenges Socrates.

Republic II.358e-362d. Glaucon on the origin of justice.

Republic II.362d-367e. Admeimantus clarifies the challenge.

In the Republic, Socrates describes what justice is and argues

that the just life is better.

Socrates develops his argument over the course of the ten books of the Republic. This makes his discussion more involved than anything we have seen in our study so far.

The opening conversation in Book I, and the challenge Plato's brothers put to Socrates in the beginning of Book II, are the first and second steps in Socrates' argument.

The Opening Conversation

The dramatic date of the Republic is uncertain. In Book I, Socrates

says it is "summer"

(Republic I.350d).

Glaucon and Adeimantus are said to have distinguished themselves at the battle

of Megara

(Republic II.368a).

There were battles there in 424 and 409 BCE. The latter date is the more likely,

as they would have been too young for the earlier engagement.

Book I is in the style of an early dialogue. Socrates' interlocutors are

Cephalus, Polemarchus, and Thrasymachus. The discussion is about δικαιοσύνη, what

it is and whether it pays.

The traditional translation of this word in this context is "justice," but it helps to see that "righteousness" works too. In the Republic, Socrates and his interlocutors are thinking about right and wrong and about whether doing what is right is always in their interest.

The question of whether the right is in our interest predates Socrates. It has always been easy to think that sometimes it is not, and one of the interesting things about Socrates is that he argued that those who think this are confused. We have seen some of this in the Gorgias. In the Republic, Plato is going further. He is giving a proof that δικαιοσύνη is always in our interest.

Socrates and Cephalus

Cephalus is the father of Polemarchus, Lysias, and Euthydemus

(Republic I.328b).

Lysias was a speechwriter. In

Against Eratosthenes,

he says that Pericles persuaded Cephalus to immigrate to Athens

(4)

and that he established and ran a prosperous shield factory in the Piraeus

(8,

19).

Cephalus has the common thought about justice and happiness.

He is rich, near the end of his life, and his conversation with Socrates turns to how he has benefited from his wealth (Republic I.330d). He suggests that wealth is good (and thus is beneficial) because it removes some of the temptation to act unjustly (Republic I.331a). The rich man can buy want he wants. He does not need to steal or cheat to get it.

After they won the Peloponnesian War (431-404 BCE), Sparta installed a regime of anti-democratic Athenian

aristocrats who became known as the Thirty Tyrants.

They brutally suppressed the opposition. Lysias and Polemarchus (who supported

the democracy) were arrested, their property and shield factory were

seized, Polemarchus was executed, and Lysias escaped to Megara

(Against Eratosthenes 12-20).

Lysias says that one of the Thirty, Melobius, in his greed and brutality,

ripped the gold earrings from the ears of Polemarchus's wife

(Against Eratosthenes 19 ).

This discussion with Cephalus introduces the main question in the

Republic: whether justice is a burden we are

sometimes better off without.

Cephalus has the common view that sometimes it is better to be unjust.

Socrates does not. He thinks that it is always better to be just.

To know who is correct, the first step is to get straight on what justice is. If we do not know this, we will not know what to consider to determine whether it is always better.

Because Cephalus has suggested that wealth protects a man from having to lie and cheat, Socrates focuses the conversation on whether "truth-telling and paying back" are what justice is. He argues that they are not because these actions are not always just.

"But, Cephalus, speaking of this very thing, justice, are we to affirm thus without qualification that it is truth-telling

and paying back what one has received from anyone, or may these very actions sometimes be just and sometimes

unjust? I mean, for example, as everyone I presume would admit, if one took over weapons from a friend who was

in his right mind and then the lender should go mad and demand them back, that we ought not to return them in

that case and that he who did so return them would not be acting justly—nor yet would he who chose to speak

nothing but the truth to one who was in that state.

You are right, Socrates.

Then this is not the definition of justice: to tell the

truth and return what one has received"

(Republic I.331c).

Cephalus agrees with Socrates and drops out of the conversation.

Socrates and Polemarchus

Polemarchus now jumps up to take his turn with Socrates (Republic I.331d).

To answer Socrates' question, Polemarchus appeals to the poet Simonides (who died about the time of Socrates' birth). He says that justice is giving each man what he is due.

"Tell me, then, you the inheritor of the argument, what it is that you

affirm that Simonides says and rightly says about justice.

That it is just to render to each his due.

In saying this I think he speaks well.

I must admit that it is not easy to disbelieve Simonides. For he is a wise and inspired man.

But just what he may mean by this you doubtless know, but I do not"

(Republic I.331e).

This exchange brings into sharper focus the point of justice.

To know what justice is, and so to move beyond the conception of justice (as paying debts, telling the truth, and so on) that Socrates and Cephalus agreed was incomplete, it is necessary to know what justice accomplishes for us and thus why it is valuable.

Polemarchus says that justice gives "each his due," but he is confused about what each is due. He thinks, for example, that someone acts justly when he helps his friends and harms his enemies, but he cannot defend this answer in questioning from Socrates.

Socrates and Thrasymachus

Thrasymachus is visiting from Chalcedon, a city at the mouth

of the Black Sea (in what is now Turkey). He seems to have first

come to Athens as part of a political embassy on behalf of his home city of Chalcedon after

it had mounted an unsuccessful revolt against Athens.

Thrasymachus breaks in to the conversation

(Republic I.336b).

He confidently tells Socrates that "justice is nothing other than the advantage of the stronger" (Republic I.338c). Thrasymachus explains that the rulers are the stronger, that they use their power to get what they want, and that "justice is the same in every city, being that which supervenes on the advantage of the established rulers" (Republic I.338e).

This conception of justice implies that unless someone is the ruler in the city, the unjust life can be better for him because it can allow him to get the more for himself.

In questioning Thrasymachus about this, Socrates introduces

the most important premise

In previous dialogues, on the interpretation I have set out, Socrates thinks that wisdom is

the virtue of the soul.

in his argument that the just life is better. He says that

justice is the virtue of the soul.

"The soul, has it a function (ἔργον) which you couldn't accomplish with anything else in the world,

as for example, to manage things, rule, deliberation, and the like, is there anything else than soul

to which you could rightly assign these and say that they were its peculiar work?

Nothing else, Socrates.

And again life? Shall we say that too is the function of the soul?

Most certainly.

And do we not also say that there is a virtue of the soul?

We do.

Will the soul ever accomplish its own work well if deprived of its own virtue, or is this impossible?

It is impossible.

Of necessity, then, a bad soul will govern and manage things badly while

the good soul will in all these things do well.

Of necessity.

And did we not agree

The agreement occurs earlier:

"But when we did reach our conclusion that justice is virtue and wisdom and

injustice vice and ignorance (τὴν δικαιοσύνην ἀρετὴν εἶναι καὶ σοφίαν, τὴν δὲ ἀδικίαν κακίαν τε καὶ ἀμαθίαν), 'Good, I said, let this be taken as established'"

(Republic I.350d).

λυσιτελέστερον ("more profitable") is a comparative form of the adjective

λυσιτελής, which is a compound word formed form the verb λύω ("free") and noun

τέλος ("end"). The question, then, is which life frees the end more, justice

or injustice. Socrates argues that it is justice.

"I tell you, Thrasymachus, I am not convinced

that injustice is more profitable than justice, not even if one gives it free

scope and does not hinder it"

(Republic I.345a).

that the virtue of the soul is justice and its defect injustice?

Yes, we did"

(Republic I.353d).

Given this premise, Socrates argues that injustice is never more profitable than justice.

"The just soul and the just man then will live well and the unjust badly?

So it appears by your reasoning, Socrates.

But surely he who lives well is blessed and happy, and he who does not the contrary.

Of course.

Then the just is happy and the unjust miserable.

So be it, Socrates.

But it surely does not pay to be miserable, but to be happy.

Of course not.

Never, then, most worshipful Thrasymachus,

can injustice be more profitable than justice"

(Republic I.353e).

Socrates thinks more than that Thrasymachus is wrong. Socrates thinks that being just, no matter the circumstances, is always more beneficial than being unjust.

Glaucon and Adeimantus Challenge Socrates

Socrates has refuted Thrasymachus, but this does not settle the answers to the two questions about justice: what justice is and whether the just life is better (Republic I.354b).

Book I thus ends in perplexity (like other early dialogues devoted to the search for a definition), but Glaucon is not content to let such an important matter go without further discussion. He tells Socrates that he is "eager to hear the nature of each, of justice and injustice, and what effect its presence has upon the soul" (Republic II.358b).

First, though, Glaucon outlines a common understanding of justice he himself wonders about.

"They say that to do wrong is by nature good, to be wronged is bad, but the suffering of injury so far exceeds in badness the good of inflicting it that when men do wrong and are wronged and taste both, those who lack the power to avoid the one and take the other determine it is for their profit to make a compact with one another neither to commit nor to suffer wrong. This is the beginning of legislation and covenants between men, that they name the lawful and the just, and it is the origin and reality (οὐσίαν) of justice " (Republic II.358e).

In the understanding Glaucon outlines, justice is an agreement that arises

among people. Because "advantage (πλεονεξίαν) is what all of nature naturally pursues as

good"

πλεονεξίαν is a form of πλεονεξία, a noun from of the

adjective πλείων ("more") and verb ἔχω ("to have").

πλεονεξίαν is a form of πλεονεξία, a noun from of the

adjective πλείων ("more") and verb ἔχω ("to have").

"[T]hat those who practice justice do so unwillingly (ἄκοντες) and from want

of power to commit injustice—we shall be most likely to apprehend that if we

entertain some such supposition as this in thought: if we grant to each, the

just and the unjust, license (ἐξουσίαν) to do whatever he wishes (βούληται),

and then accompany them in imagination and see whither his desire will conduct

each. We should then catch the just man in the very act of resorting to the

same conduct as the unjust man because of the advantage (πλεονεξίαν) which

every creature by its nature pursues as a good, while by the convention of law

it is forcibly diverted to paying honor to equality. The license that I

mean would be most nearly such as would result from supposing them to have the

power which men say once came to the ancestor of Gyges the Lydian. ... [Once

he realized the ring he found gave him the power to be invisible], he

immediately managed things so that he became one of the messengers who went up

to the king, and on coming there he seduced the king's wife and with her aid

set upon the king and slew him and possessed his kingdom. If now there should

be two such rings, and the just man should put on one and the unjust the

other, no one could be found, it would seem, of such adamantine temper as to

persevere in justice and endure to refrain his hands from the possessions of

others and not touch them, though he might with impunity take what he wished

even from the marketplace, and enter into houses and lie with whom he pleased,

and slay and loose from bonds whomsoever he would, and in all other things

conduct himself among mankind as the equal of a god. And in so acting he would

do no differently from the other man, but both would pursue the same course.

And yet this is a great sign, one might say, that no one is just of his own

will (ἑκὼν) but only from constraint, in the belief that justice is not his

personal good, inasmuch as every man, when he supposes himself to have the

power to do wrong, does wrong. For that there is far more profit

for him personally in injustice than in justice is what every man believes,

and believes truly, as the proponent of this theory will maintain"

(Republic II.359b).

(Republic II.359c),

they think the best option is to act

unjustly and make others victims. Most, however, realize this is

impossible for them because

they lack the power.

Since allowing themselves to be victims is the worst of the four

options, this leaves the choices to act justly

and to act unjustly. To avoid the injury they would suffer from acting unjustly, people

choose to act justly.

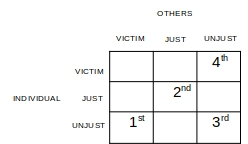

(The grid orders the outcomes from the point of view of the individual. It portrays the best outcome as the one in which the individual acts unjustly and makes the others his victims. The second best outcome for the individual is the one in which he acts justly and so do the others. In the third best, everyone acts unjustly but he is not always the victim. In the fourth and worst outcome for the individual, the others act unjustly and make him their victim.)

To prove it is best to act unjustly and make others one's victims, Glaucon retells a story about a shepherd who found a ring that gave him the power to get away with acting unjustly because it made him invisible. Glaucon says that the many think there would be no reason not to use such a ring if someone found one, and he challenges Socrates to show that the many are wrong.

"[No one, Socrates,] has ever censured injustice or commended justice

otherwise than in respect of the repute, the honors, and the gifts that accrue

from each. But what each one of them is in itself, by its own inherent force,

when it is within the soul (ψυχῇ) of the possessor and escapes the eyes of

both gods and men, no one has ever adequately set forth in poetry or prose—the

proof that the one is the greatest of all evils that the soul contains within

itself, while justice is the greatest good.... [M]ake clear to us what each in

and of itself does to its possessor, whereby the one is evil and the other

good. But do away with the repute of both, as Glaucon urged. For, unless you

take away from either the true repute and attach to each the false, we shall

say that it is not justice that you are praising but the semblance, nor

injustice that you censure, but the seeming, and that you really are exhorting

us to be unjust but conceal it, and that you are at one with Thrasymachus in

the opinion that ... injustice is advantageous and profitable to oneself but

disadvantageous to the inferior. ...[T]his is what I would have you praise

about justice—the benefit which it and the harm which injustice inherently

works upon its possessor. But the rewards and the honors that depend on

opinion, leave to others to praise. For while I would listen to others who

thus commended justice and disparaged injustice, bestowing their praise and

their blame on the reputation and the rewards of either, I could not accept

that sort of thing from you unless you say I must, because you have passed

your entire life in the consideration of this very matter. Do not then, I

repeat, merely prove to us in argument the superiority of justice to

injustice, but show us what it is that each inherently does to its

possessor—whether he does or does not escape the eyes of gods and men—whereby

the one is good and the other evil"

(Republic II.366e).

Adeimantus clarifies this challenge Glaucon puts to Socrates.

He tells Socrates that he must show that justice is better and injustice worse, not because of such things as reputation but, because of their presence in the soul.

Adeimantus, in this way, requires that Socrates demonstrate what Socrates forced Thrasymachus to admit: that "the virtue of the soul is justice and its defect injustice" (Republic I.353e) and that those whose souls are just are happier than those whose souls are not just.

The Origin and Reality of Justice

The common conception of justice Glaucon wonders about and outlines is similar to the conceptions Protagoras and Callicles describe in the Protagoras and the Gorgias.

In the Protagoras, in the myth Protagoras tells, human beings were originally unable to live together in cities because they could not get along well enough. To solve this problem, and thus to save the human race from extinction, Zeus brings about a change in the human psychology so that it contains the potential to act rightly in connection with group living. The specific form this potential takes is a matter of an agreement in attitudes about how to behave.

"Men dwelt separately in the beginning, and cities there were none; so that they were being destroyed by the wild beasts, since these were in all ways stronger than men; and although their skill was a sufficient aid in respect of food, in their warfare with the beasts it was defective; for as yet they had no political art, which includes the art of war. So they sought to band themselves together and secure their lives by founding cities. Now as often as they were banded together they did wrong to one another through the lack of political art, and thus they began to be scattered again and to perish. So Zeus, fearing that our race was in danger of utter destruction, sent Hermes to bring shame and right (δίκην) among men, so that there should be regulation in cities and friendly ties to draw men together" (Protagoras 322a).

In the Gorgias, Callicles says that this agreement is a trick the weak use to protect themselves.

"Those who lay down the rules are the weak men, the many. And so they lay down the rules and assign their praise and blame with their eye on themselves and their advantage. They terrorize the stronger men capable of having more. To prevent these men from having more than themselves they say that taking more is shameful and unrighteous (ἄδικον), and that unrighteousness is this, seeking to have more than other people. They are satisfied, I take it, if they themselves have an equal share when they're inferior. That's why by convention this is said to be unrighteous and shameful, to seek to have more than the many, and they call unrighteousness. But I think nature itself shows this, that it is just for the better man to have more than the worse, and the more powerful than the less powerful" (Gorigias 483b).

Given the traditional ordering of the dialogues, this shows that Plato has been thinking for some time about what justice is and whether it is always beneficial as Socrates has claimed.

In the Republic, as we are seeing and will continue to see, he has worked out a proof.

Perseus Digital Library

Plato's,

Protagoras,

Gorgias,

Republic

Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon

ἄκων (Attic contraction for ἀέκων), akōn, adjective, "unwilling, under constraint"

ἑκὼν, hekōn, adjective, "wittingly, purposely," opposite of ἄκων

δικαιοσύνη, dikaiosynē, noun, "justice"

ἐξουσία, exousia, noun, "power to do a thing"

ἰσονομία, isonomia, noun, "equality of political rights"

λυσιτελής, lysitelēs, adjective,

(λύω ("unbind, unfasten") +

τέλος ("end")), "profitable"

Θρασύμαχε, Thrasymache, proper name (from θρασύμαχος, thrasymachos, adjective,"bold in battle")

ὅρος, horos, noun, "boundary"

πόλις, polis, noun, "city"

πλεονεκτέω, pleonekteō, verb, "to claim more"

πλεονέκτης, pleonektēs, noun (formed from adjective), "the one who has or claims more (ὁ πλέον ἔχων)

πλεονεξία, pleonexia, noun, "advantage"