ARISTOTLE

The First Great Platonist and Plato's First Great Critic

Plato, 427-347 BCE. Aristotle, 384-322 BCE.

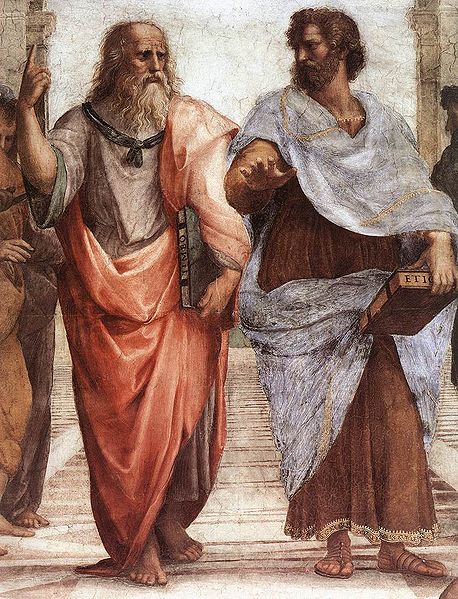

Raphael Sanzio da Urbino (1483-1520), The School of Athens

Plato points to a "higher" reality. Aristotle points forward.

He accepts what he regards as the central parts of Platonism, but he

also is a critic who eliminates its

excesses.

Plato holds a copy of the Timaeus, a late dialogue devoted to cosmology.

Aristotle holds a copy of a work in ethics.

The titles TIMEO and

ETICA on these books translate from Italian into English as TIMAEUS and ETHICS.

Aristotle belongs to the Period of Schools.

He entered Plato's Academy in 367 BCE when he was seventeen and remained

until Plato's death in 347 BCE.

In 335 BCE, Aristotle founded his school in the Lyceum (a gymnasium located outside and east of Athens's city wall).

The Aristotelian Corpus

As we now have it, the works in the Aristotelian corpus are esoteric (written for members of the school) and organized systematically into roughly three subjects. The logical works come first. They are followed by the physical works. The ethical works are last. From this systematic ordering, the original chronological ordering is not very easy to see.

This makes the Aristotelian corpus a little different from the Platonic corpus.

We can see in Plato's dialogues the development of his thought in his reaction to Socrates, and although some of the conversations are more challenging than ones we have in everyday life, Plato did not write his dialogues expressly for insiders. He models his early dialogues on conversations Socrates had, and these conversations were not with philosophers.

The works in Aristotle's corpus are also less finished than many of Plato's dialogues. Some of Aristotle is easy to read, but a lot of it is little more than a series of compressed notes.

Platonist and Plato's Critic

These differences can sometimes make Aristotle hard to understand, but our general strategy will be the same one we used to understand Plato. Socrates was Plato's greatest influence. Plato is Aristotle's. Aristotle spent twenty years in Plato's Academy. Just as we assumed Plato was trying to understand what was right and to correct what was wrong in what Socrates thought, we are going to work through the Aristotelian corpus in roughly its systematic ordering on the assumption that Aristotle is trying to understand what was right and to correct what was wrong in what he learned from Plato during his time as a student in the Academy.

Aristotle's work called the Physics shows us this general line of thought.

The Physics is the first work in Aristotle's physical works. It is an inquiry into the truths that hold throughout nature. Subsequent works in the physical works are discussions of specific parts of nature. On the Soul, for example, which we will consider in a later lecture, is the first work in the physical works about the nature of "ensouled" and hence living beings. ψυχή is the Greek noun translated as "soul." ἔμψυχος is formed with the prefix ἐν ("in"). It means "alive."

Aristotle, with his interest in nature, is following Plato against Socrates.

Plato disagreed with Socrates about whether knowledge of the reality of things is part of wisdom. Whereas Socrates thought that all we need to know is what is good and what is bad, Plato thought that the soul forgets itself when it descends into the body and that the best life a soul can live in the body is one of managing its time so that as much as possible it recovers the knowledge of reality it once possessed when it was apart from the body.

Plato tries to describe this reality in the Timaeus. This traditionally is a late dialogue. Plato wrote it late in his life and after Aristotle had become a member of the Academy.

Timaeus, not Socrates, leads the discussion.

He is the

"best astronomer and has made it his special task to know about the nature of the whole"

(27a).

He begins with "the origin of the cosmos" and ends "with the

generation of man."

In this discussion, he explains the existence of sensible things

Timaeus describes sensible things as the "offspring" of the forms

and the receptacle

(Timaeus 50d).

He supposes that before the god created the cosmos,

the traditional elements (fire, water, earth and air) were

"without reason and measure"

(Timaeus 53a),

that the god formed them to "be as beautiful and excellent as possible"

(Timaeus 53b),

and that he constructed the rest of the cosmos from them.

"For at that time [before the demiurge did his work] nothing had a share in these proportions save by chance, and there

was nothing at all worthy of being called by the names we now use, such as fire or water or any of

the others. Rather he first set all of these in order, then constructed this universe from them; a

single living being containing within itself all living beings both mortal and immortal. He himself

was indeed the artificer of the divine beings and he commanded his own offspring to undertake

the creation of the mortals.

And they, imitating their father, received the immortal beginning of soul, then fashioned a mortal

body in a globe around it, for it, and bestowed the entire body as its vehicle and also built on

another form of soul in the body: the mortal form"

(Timaeus 69b),

in terms of

forms

(27d),

the divine maker ("artificer" or "demiurge" (δημιουργός) who is supremely good and

brings a cosmos into existence as like himself as possible

(30a),

and

the "receptacle" (ὑποδοχή)

that becomes like the forms (49a).

We can begin to understand Aristotle's approach and contribution to philosophy if we understand him as trying to remove the problems he sees in this picture of reality in the Timaeus. Aristotle accepts, as we will see, that there is teleology in nature but rejects that things are the way the are because of the actions of a divine maker. He understands the existence of living things in terms of forms but does not think these forms exist as Timaeus describes them. Instead of the existence of the receptacle, Aristotle has what he calls matter.

Existence in the World of Natures

Aristotle, as we will see, talks about forms in his description of the kind of existence he takes what he calls "substances" (οὐσίαι) to possess. Aristotle's understanding of substances and their existences takes work to understand in detail, but the initial idea is that

• human beings and other sensible substances have natures

• their natures are organizations of their matter

• these organizations are the forms of sensible substances

We will look at details in the next several lectures, this is enough for us to begin to see why the logical works are traditionally first and the physical works second in Aristotle's corpus.

Demonstrations in Physics

"demonstration" (ἀπόδειξις) The logical works build to an explanation of what Aristotle understands as the grasp of reality we achieve when we have the kind of understanding he calls a demonstration.

In the logical works, the Categories is first. It discusses terms, the parts of sentences. On Interpretation is second. It discusses sentences, the parts of deductive arguments. The Prior and Posterior Analytics are next. The Prior Analytics discusses deductive arguments, and the Posterior Analytics discusses the subset of these arguments that are demonstrations.

Definitions give what Aristotle calls "the what it is to be."

"the what it is to be" (τὸ τί ἦν εἶναι)

τὸ τί ἦν εἶναι is sometimes translated as "essence." The what it is to be gives the being,

and οὐσία was translated from Greek to

Latin as

essentia

in this context.

οὐσία is a noun formed from a participle of εἶναι ("to be") and a noun-forming suffix -ία.

Because Latin had the suffix but not the participle of esse ("to be"),

the participle essens was introduced into the language so that the word essentia

could be formed in imitation of the way οὐσία is formed in Greek.

Seneca, in his Epistles 58.6,

uses essentia and cites the authority of Cicero to justify it as a Latin word.

For the imperfect in τὸ τί ἦν εἶναι, see

Smyth 1901-1902

and "F" in the entry for

εἰμί in Liddell and Scott.

In the case of sensible substances of a given kind, this definition specifies the form in matter.

Demonstrations that have this definition as their major premise are deductive arguments

that are supposed to help us know

why these substances have the behaviors they possess as members of

the kind.

"A deduction (συλλογισμός) is an argument in which, certain things having been

supposed, something different from those supposed results of necessity because

of their being so"

(Prior Analytics I.1.24b).

"The reason why we must deal with deduction before we deal with demonstration is that deduction is more universal; for demonstration (ἀπόδειξις)

is a kind of deduction, but not every deduction is a demonstration"

(Prior Analytics I.4.25b).

"The starting-point of every demonstration is the what it is (τὸ τί ἐστιν)"

(On the Soul I.403a).

In a syllogism, there are three terms: "subject" (S), "middle"

(M), and "predicate" (P). Each premise has one term in

common with the terms in the conclusion. In the major premise, the predicate

is the common term. In the minor premise, the subject is the common term.

It is customary to write the major premise first. This can seem unnatural

until one realizes Aristotle does not write "All M are P."

Instead, he writes "P is predicated of all M." So when the premises and

the conclusion are expressed in the form Aristotle uses, the demonstration

All M are P

All S are M

----

All S are P

takes the form

P is predicated of all M

M is predicated of all S

----

P is predicated of all S

"For if A is predicated of all B, and B of all

C, A must necessarily be predicated of all C"

(Prior Analytics I.4.25b).

Aristotle's theory of the syllogism is major achievement in logic that was only surpassed

in the last hundred years or so.

Aristotle takes human beings to be sensible substances, so we can use them

in an example demonstration.

Aristotle does not give the definition, as his works are exploratory, but for the example

we can suppose that to be a human

being is to be a rational animal.

This definition gives us "the what it is to be." In the demonstration we are constructing, it appears as the major premise. It tells us that humans are beings whose matter is in the organization and form of a rational animal, and the minor premise tells us that part of being a rational animal is possessing the power to use sensations to have beliefs.

Rational animals can use their sensation to have beliefs.

(All M are P)

Human beings are rational animals.

(All S are M)

----

Human beings can use their sensations to have beliefs.

(All S are P)

Aristotle's idea is that this demonstration would show us some of the structure that characterizes human existence. Human beings are each matter in the form of a rational animal. This is the reality and "what it is to be" human, and it is a consequence of this organization of matter that human beings possess the power to have beliefs in terms of sensations.

The Life of a Philosopher

This example helps us begin to see why Aristotle thinks of physics as philosophy.

Plato, in the Phaedo, as we saw, makes Socrates describe the φιλόσοφος as someone who devotes his life to possessing knowledge of forms. These forms he describes as the unchanging, invisible reality of things we grasp not through the senses but in the exercise of reason.

"Is the

reality itself (αὐτὴ ἡ οὐσία), whose reality we give an account in our

dialectic process of question and answer, always the same or is it liable to

change? Does the equal itself, the beautiful itself, what each thing itself is, the reality, ever

admit of any change whatsoever? Or does what each of them is, being uniform and existing

by itself, remain the same and never in any way admit of any change?

It must necessarily remain the same, Socrates.

But how about the many things, for example, men, or horses, or cloaks, or any other such

things, which bear the same names as those objects and are called beautiful or

equal or the like? Are they always the same? Or are they, in direct opposition to those others,

constantly changing in themselves, unlike each other, and, so to speak, never the same?

The latter, they are never the same.

And you can see these and touch them and perceive them by the other senses,

whereas the things which are always the same can be grasped only by the reasoning of the intellect (τῷ τῆς διανοίας λογισμῷ),

and are invisible and not to be seen?

Certainly that is true.

Now, shall we assume two kinds of existences, one visible, the other invisible?

Let us assume them, Socrates"

(Phaedo 78c).

Aristotle applies this idea to sensible substances. He thinks that these substances have an unchanging reality, that this reality is the form in the matter, that we know this form in reason, and that this knowledge is the basis for the account we give in demonstrations.

Although this shows of some of why Aristotle thinks of physics as philosophy,

δευτέρα φιλοσοφία, "second philosophy"

The noun φιλοσοφία more literally means "love of wisdom." This is how we translated

Socrates when Plato made him say he would not abandon φιλοσοφία. Aristotle

works in this same tradition, but we are familiar enough with

this tradition now to use the conventional translation.

πρώτη φιλοσοφία, "first philosophy"

it does not explain why he thinks it is second philosophy and thus

is second to first philosophy.

To understands this we need to take a closer look at how Aristotle understands sensible substances and the existence of substances more generally. This will take us to Aristotle's Metaphysics. It a collection of books between the physical and the ethical works.

Thinking about Aristotle

Aristotle is not easy, but we have a strategy for understanding what he thought.

We are looking to see how he supplies missing details in the thought he knew from his time in Plato's Academy and how he removes what he regards as its mistakes and excesses.

To see how Aristotle does this, we are thinking about his reaction to Plato's account of reality in the Timaeus. In this dialogue, Timaeus explains the existence of living things in the cosmos in terms of forms and the work of a supremely good divine maker. We are trying to understand what part of this account Aristotle accepts and what part he rejects.

Our first step, to which we now turn, is Aristotle's theory of sensible substances.

Perseus Digital Library

Plato,

Theaetetus,

Timaeus

Aristotle,

Metaphysics

Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon

ἀπόδειξις, apodeixis, noun, "showing forth, making known, exhibiting"

ἐξωτερικός, exōterikos, adjective, "outer"

(a comparative of ἔξω, exō, adverb, "out")

ἐσωτερικός, esōterikos, adjective, "inner" (coined to correspond to ἐξωτερικός)

κόσμος, kosmos, noun, "order"

φιλοσοφία, philosophia, noun, "love of wisdom"

συλλογισμός, noun, "computation, calculation"

Arizona State University Library: Loeb Classical Library:

Aristotle,

Categories,

On Interpretation,

Prior Analytics,

Posterior Analytics,

Physics

"Aristotle wants to hold on to the metaphysical primacy of objects, natural

objects, living objects, human beings. He does not want these to be mere

configurations of more basic entities, such that the real things

turn out to be these more basic entities. But

to look at an object [as Aristotle thinks the inquirers into nature do] just as the configuration of material constituents

transiently happen to enter into is to look at the material constituents as the

more basic entities"

(Michael Frede, "On Aristotle's Conception of the Soul," 146. Essays on Aristotle's De Anima, 93-107).

"Horses are a kind of beings, and camels are a different

kind of beings, but neither horses nor camels have a distinctive way of being,

peculiar to them; they both have the way of being of natural substances..., as

opposed to, e.g., numbers which have the way of magnitudes..."

(Michael Frede, "The Unity of General and Special Metaphysics: Aristotle's Conception of

Metaphysics," 85-86. Essays in Ancient Philosophy, 81-95).

"Aristotle's view of the world is such that the behavior of things in the celestial

spheres is governed by strict regularity dictated by the nature of the things involved.

But once we come to the sublunary, grossly material sphere in which we live, this

regularity begins to give out. It turns into regularity 'for the most part,' explained

by the imperfect realization of natures in gross matter. What is more, these

regularities, dictated by the natures of things, even if they were exceptionless, would

leave many apsects of the world undetermined"

(Michael Frede, A Free Will, 28).