SENSIBLE SUBSTANCES

The natures of sensible substances are forms in matter

To call something a substance is to attribute a kind of existence

to it.

In each sensible substance (a substance we can experience though the senses),

The noun nature is from the Latin

natura.

This was a standard translation of the Greek noun

φύσις.

The Latin noun

physica

transliterates the substantive use (the use as a noun) of the Greek adjective

φυσική.

In the phrase 'inquiry into nature,' the Greek for 'inquiry' is

ἱστορία.

This Greek noun transliterates as historia.

The title of Herodotus's Histories is Ἱστορίαι.

"This is the display of the inquiry (ἱστορίης) of Herodotus of Halicarnassus,

so that things done by man not be forgotten in time, and that great and marvelous deeds,

some displayed by the Hellenes, some by the barbarians, not lose their glory,

including among others what was the cause of their waging war on each other"

(Histories I.1).

The term 'natural history' (as in the name of the AMNH in NYC) preserves some of the ancient sense of 'inquiry

into nature' (ἱστορία περὶ φύσεως). This is due in part to the importance in

the history of science of Aristotle's Περὶ Τὰ Ζῷα Ἱστορίαι ("Inquiries about

Animals"), which is now commonly called by its Latin title Historia

Animālium or English translation

History of Animals.

Book II of the Physics:

Chapter 1. The nature in a thing

Chapter 2. The physicist

Chapter 3. Causes.

Chapter 4. Outcomes by luck and by accident

Chapter 5. Luck

Chapter 6. Accident

Chapter 7. Summary thus far

Chapter 8. The for something

Chapter 9. Necessity

"Of things that are, some are by nature, some because of other causes.

By nature are the animals and their parts, and the plants and the simple

bodies (earth, fire, air, water)—for we say these and the like exist by

nature. They seem distinguishable from

things not united by nature. Each of the beings that exist by nature has within itself a

starting-point of change and staying unchanged"

(Physics II.1.192b).

"For nature is a starting-point and cause of

being moved and of being at rest in that to which it belongs primarily according to

itself and not accidentally"

(Physics II.1.192b).

"Nature is said to be the shape and form according to the

account [of what the object is]"

(Physics II.1.193a).

"What is potentially flesh or bone has not yet its own nature, and does not

exist by nature, until it receives the form according to the account (τὸ εἶδος τὸ κατὰ τὸν λόγον),

which we say in defining what flesh or bone is. ... So

the nature of things having a starting point of change is the

shape or form, which is not separable except according to the account . ... And this is more [what] nature [is] than

the material [is what nature is]"

(Physics II.1.193b).

"separate" (χωριστὸν)

"To what point should the physicist know the form and the what it is (τὸ εἶδος

καὶ τὸ τί ἐστιν)? ... [To the point of knowing] what is separable in form but in

matter (χωριστὰ μὲν εἴδει, ἐν ὕλῃ δέ) ... What is separable [without qualification], and how

things are with it, is the work of first philosophy to determine"

(Physics II.2.194b).

Aristotle thinks there is something he calls a "nature" (φύσις). For human beings and other sensible substances, Aristotle describes this nature as a

"starting point of change and staying unchanged"

(Physics II.1.192b).

We can get some insight into what Aristotle is thinking by recalling something Socrates says in the Protagoras. In his discussion of whether pleasure can overcome knowledge, Socrates thinks the dialectic has shown that this sort of behavior is not "in human nature."

"Then [given what has been agreed,] no one willingly goes after bad or what he thinks to be bad; it is not in human nature (ἐν ἀνθρώπου φύσει), apparently, to do so—to wish to go after what one thinks is bad in preference to the good; and when compelled to choose one of two bads, nobody will choose the greater when he may choose the lesser" (Protagoras 358c).

Aristotle, like Socrates, believes in "human nature" and thinks that it causes human beings to behave in the specific ways they do (the ways that belong to human beings as a species).

Aristotle, however, asks a question Socrates does not. Aristotle asks what a nature is in the existence of a sensible substance so that human nature and other natures are causes.

Natures are Forms in Matter

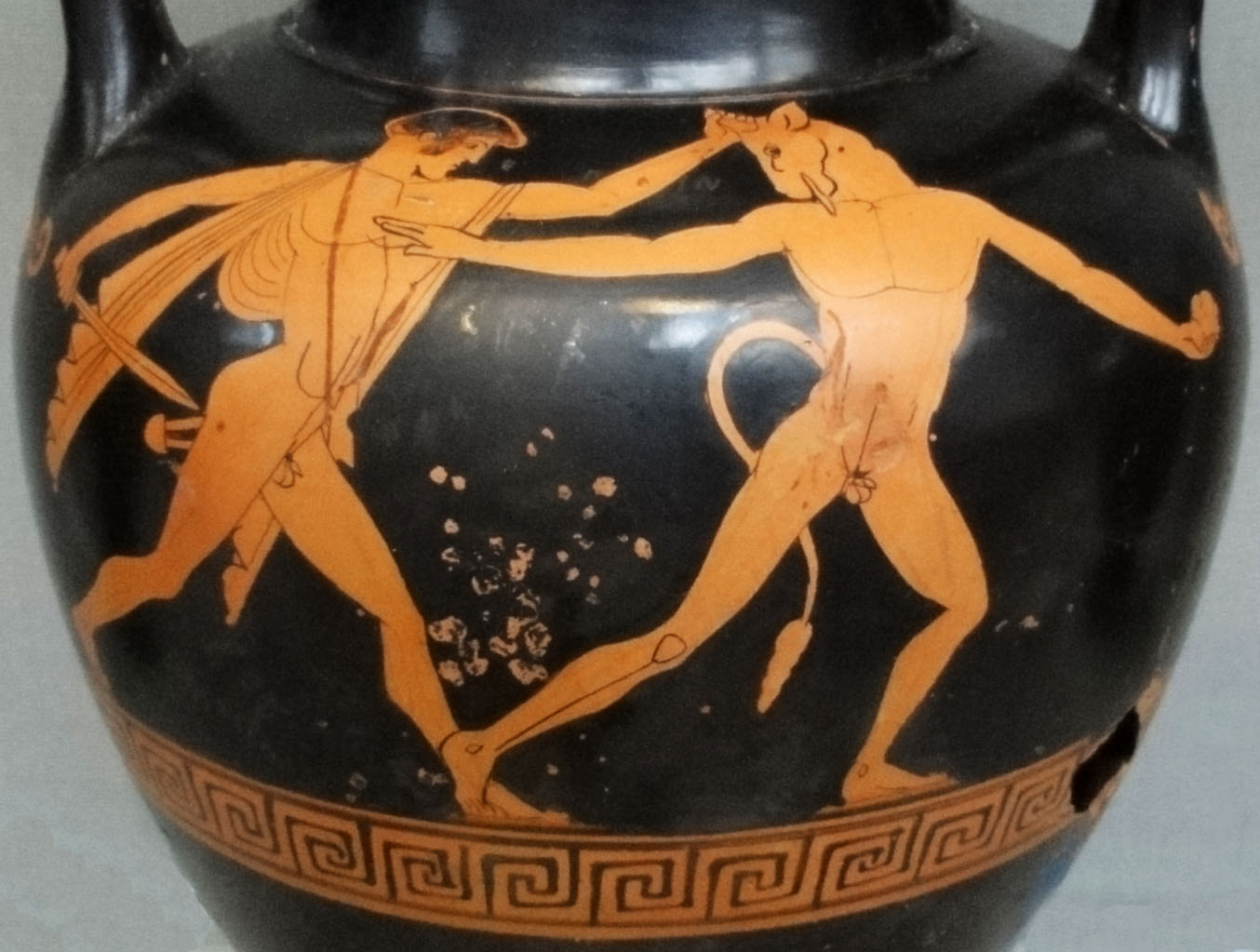

Theseus slays the Minotaur.

In the Phaedo, Echecrates

asks why Socrates spent so much time in jail after

his conviction. Phaedo answers that the execution was delayed because the ship

of Theseus had not returned from Delos. Athens was to be kept pure until the

ship returned, so no executions were carried out.

Delos (Δήλος) is an island in the Aegean Sea.

To understand Aristotle's answer, it helps to consider what happened in the history he knows.

The inquirers into nature after Parmenides eliminated the objects we traditionally think exist. Democritus explained them away as a product of a "bastard" way of thinking about atoms in the void. In this understanding, what we traditionally believe are objects are illusions our minds create. Atoms together in the void appear to us as objects we wrongly take to be real.

Against this Presocratic tradition, Aristotle follows the general line of thought in the Timaeus that these objects are real and that forms play a role in the explanation of their existence.

Aristotle thinks that the natures of sensible substances are forms, but he understands the existence of these forms in a new way. He does not think their existence is separate as Plato seems to have thought. Aristotle says they are "in matter" and "separate in account."

Now we need to know what Aristotle means by "in matter" and "separate in account."

The Ship of Theseus

"The ship on which Theseus sailed with the youths and returned in safety, the

thirty-oared galley, was preserved by the Athenians down to the time of

Demetrius Phalereus [fourth to third century BCE]. They took away the old

timbers from time to time, and put new and sound ones in their places, so that

the vessel became a standing illustration for the philosophers in the mooted

question of growth, some declaring that the vessel remained the same, others that it

was not the same"

(Plutarch, Life of Theseus 23

(in Parallel Lives (a set of biographies of famous men))).

To help ourselves get this knowledge, we can engage in a thought

experiment.

The subject of this experiment is the ship of Theseus. This ship was known to be ancient in Socrates' day and to have been repaired many times. The philosophical question is what in the ship persists when it continues to exist as itself over the years through its many repairs.

The material from which the ship is built does not seem to be the answer. After the boards and other materials were replaced, the repaired ship is still the ship of Theseus.

It seems instead that the unrepaired and repaired ship are the same ship if the material has the same organization. The original organization must be present for the ship to exist.

Aristotle has this sort of view about sensible substances. Their nature is an organization of material so that there is something that behaves as members of the kind behave.

Aristotle's Theory of Forms

Now we can see how the forms of sensible substances are in matter and separate in account.

The form of a ship is the particular organization of the pieces of wood and other materials so that there exists a ship of a certain kind. Removing this organization from these materials causes the organization to go out of existence as it destroys the ship by taking it apart. In the absence of this organization, there is no ship of Theseus. Instead, there is only a pile of planks of wood and other materials we might use to try to put the ship back together.

There is a way, though, according to Aristotle, that the form is separate from the matter.

The ship of Theseus is a galley, and a ship of this form is a ship that functions in a certain way. It is a ship propelled primarily by oars, has a shallow draft, and has low freeboard. This description makes no mention of the pieces of wood and other things we use to build galleys. This, Aristotle thinks, makes the form of the ship separate from the matter in account.

When Aristotle says that the form is "in matter" and "separate in account," he is giving what he takes to be the truth in Plato's conception of the existence the forms of human beings and other such things experience leads us to believe are real. Aristotle thinks Plato was right that the forms of these things are separate, but he thinks that Plato was wrong to believe that these forms are separate without qualification. As Aristotle understands the forms of sensible substances, they exist in matter and are separately from it only "in account."

To see the difference from Plato's view, it helps to remember the picture in the Timaeus. The divine maker constructs the cosmos by using the form of a living creature as his model (Timaeus 37c). This form contains the forms of the other living creatures (Timaeus 39e). The maker constructs the "heavenly race of gods" and tasks them to construct the living creatures subject to death by imitating what he himself did to construct these gods (Timaeus 41c).

Whereas Plato makes the forms exist apart and prior to the "living creatures," Aristotle makes the forms of each of the sensible substances numerically distinct but identical in account.

"Your matter and form and moving cause are different from mine, but they are the same in their general account [because we are both human beings]" (Metaphysics XII.5.1071a).

Each form is a numerically distinct organization of matter. These forms are not apart and prior. They do not exist for the divine maker to use in its construction of the cosmos.

"Don’t be surprised, Socrates, if in many cases on numerous subjects regarding the gods and the generation of the universe, we prove unable to furnish accounts entirely and in every way consistent with themselves and exact. Indeed if we can offer an account that is as likely as any other, we should be content, remembering that I who speak, and you who judge, possess a human nature and so it becomes us to allow the likely story (εἰκότα μῦθον) about these matters and forbear to search beyond it" (Timaeus 29c). Timaeus himself tells Socrates he should not take this account as more than a "likely story," and Aristotle as a Platonist and Plato's critic is trying to put the account on firmer ground.

Thinking More about Aristotle

In addition to his new way of thinking about the forms of sensible substances, Aristotle also reimagines the teleology in the Timaeus. In the Timaeus, the model for the teleology is the craftsman. As we will see, Aristotle rejects the craftsman but keeps the teleology.

Perseus Digital Library

Aristotle,

Metaphysics

A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities: THEO´RIS (θεωρίς),

THEO´RI (θεωροί)

Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon

θεωρία, theōria, noun, "a sending of" θεωροί or "state-ambassadors" to the oracles or games,

or, collectively,

the θεωροί themselves, "embassy, mission"

θεωρίς, theōris, noun, "sacred ship, which carried the θεωροί to their destination"

θεωρός, theōros, noun, "envoy," ("spectator" in the sense of "overseer")

κόσμος, cosmos, noun, "order"

παράδειγμα, paradeigma, noun, "paradigm"

The θεωροί ("overseers") were sacred ambassadors sent on

special missions (θεωρίαι) to perform some religious duty for the state,

to consult an oracle, or to represent the state at some religious

festival. In Athens, it seems that three ships carried the θεωροί: the

Delia (Δηλία), the Salaminia (Σαλαμινία), and the Paralus (Πάραλος).)

The Greeks thought that the Δηλία was very old and that it

had once taken Theseus to Crete.

Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short,

A Latin Dictionary

natura

physica

Arizona State University Library. Loeb Classical Library.

Aristotle, Physics

"Aristotle thinks that the capacity of an object to behave in this

characteristic way [that characterizes it as a member of a natural kind]

depends on its organization, structure, and disposition, indeed, he thinks that

it is just this disposition or organization that enables the object to behave

the way it does. Now, for Aristotle, the form is this disposition or

organization, while the matter is what is thus disposed or organized.

How could the form, so construed, satisfy the requirements laid down for being

a substance?

An important requirement was that the substance was to explain why, despite

all the changes an object had undergone, it still is the same object. How the

form could satisfy this requirement, we can see from the ancient example,

expanded by Hobbes, of Theseus's ships, Theoris, which for centuries

has been sent to Delos on an annual pilgrimage and whose return Socrates, in

the Phaedo, must await before he may drink the poison.

Over the

years, the ship is repaired, plank by plank, always, however, according to the

original plan. Now, let us suppose there is a shipwright who keeps the old

planks. After all the old planks have been replaced in Theoris, he

puts them together again according to the original plan and thus has a second

ship. It seems obvious to me that this ship, even though it is constructed

from all the old planks and according to the original plan, is not the old

ship, Theoris, but a new ship; the ship constructed from the new

planks is, in fact, the old ship. ...

What makes for the identity of the repaired ship with the original ship is

obviously a certain continuity. This is not the continuity of matter, or of

properties, but the continuity of the organization of changing matter, an

organization which enables the object to function as a ship, to exhibit the

behavior of a ship"

(Michael Frede, "Individuals in Aristotle," 66. Essays in Ancient Philosophy, 49-71).

"But, there is another line of argument which suggests that separate substances

are paradigmatic as substances. Perhaps the most important characteristic of

substances is that they exist in their own right, that they do not depend for their

existence on something else, or, as Aristotle puts it, are separate. Now this requirement notoriously admits of various interpretations. But it seems that, on

any plausible interpretation of it, it is only separate forms that satisfy this requirement straightforwardly. They do not in any sense need matter, or non-

substantial characteristics, i.e., qualities, quantities, places, etc., or anything

else to be realized. The forms of sensible substances are separate, too, but only

qualifiedly so, namely, separate in account; the account of a form is self-

contained in that it does not involve a reference to any other item in the ontology.

Still, a material form needs some matter, and the composite substance needs

nonessential properties, though these properties and their matter do not form

part of the account of the form. ... Hence, separate forms satisfy all three requirements of substancehood

mentioned in Z 3 straightforwardly, whereas the forms of sensible substances

meet them only in some indirect or qualified way" (Michael Frede, "The Unity of General and Special Metaphysics: Aristotle's

Conception of Metaphysics," Essays in Ancient Philosophy, 90-91).