THE PERIOD OF SCHOOLS

Aristotle. The Lyceum.

Aristotle.

384 - 322 BCE

Aristotle's followers were called Περιπατητικοί (Peripatētikoi)

because he discussed philosophy while he was walking and his students

were following him in the

περίπατος or "covered walk" of the Lyceum.

The Lyceum

(Λύκειον) was the site of Aristotle's school.

"The associates of Aristotle were called the Peripatetics, because they used to debate while walking in the

Lyceum

(Cicero,

Academica I.4.17).

Peripateticus

is the Latin translation of

Περιπατητικός.

Aristotle belongs to the Period of Schools. His school is the Lyceum.

Aristotle is the first great Platonist and Plato's first great critic. He accepts the big picture of what Plato thought, but tries to correct what he regards as its excesses and mistakes.

The Aristotelian Corpus

After Aristotle's death in 322 BCE, the history of his corpus is uncertain.

"From Scepsis [a center of learning in

the Attalid dynasty of Pergamum] came the Socratic philosophers

Erastus and Coriscus and Neleus the son of Coriscus, this

last a man who not only was a pupil of Aristotle and Theophrastus,

but also inherited the library of Theophrastus, which included that of

Aristotle. At any rate, Aristotle bequeathed his own library to

Theophrastus, to whom he also left his school; and he is the first man,

so far as I know, to have collected books and to have taught the kings

in Egypt how to arrange a library. Theophrastus bequeathed it to Neleus;

and Neleus took it to Scepsis and bequeathed it to his heirs, ordinary

people, who kept the books locked up and not even carefully stored. But

when they heard how zealously the Attalic kings to whom the city was

subject were searching for books to build up the library in Pergamum,

they hid their books underground in a kind of trench. Much later,

when the books had been damaged by moisture and moths, their descendants

sold them to Apellicon of Teos for a large sum of money, both the

books of Aristotle and those of Theophrastus. Apellicon was a bibliophile

rather than a philosopher; and therefore, seeking a restoration of the parts

that had been eaten through, he made new copies of the text, filling up the gaps

incorrectly, and published the books full of errors. The result was that the

earlier school of Peripatetics who came after Theophrastus had no books at all,

with the exception of only a few, mostly exoteric works, and were therefore able

to philosophise about nothing in a practical way, but only to talk bombast about

commonplace propositions, whereas the later school, from the time the books in

question appeared, though better able

to philosophize and Aristotelize, were forced to call most of their statements

probabilities, because of the large number of errors. Rome also contributed

much to this; for, immediately after the death of Apellicon, Sulla, who had

captured Athens, carried off Apellicon’s library to Rome, where Tyrannion the

grammarian, who was fond of Aristotle, got it in his hands by paying court to

the librarian, as did also certain booksellers who used bad copyists and would

not collate the texts—a thing that also takes place in the case of the other

books that are copied for selling, both here [in Rome] and at Alexandria. However, this

is enough about these men"

(Strabo,

Geography XIII.1.54).

"Sulla seized for himself the library of Apellicon of Teos, in which were most of

the treatises of Aristotle and Theophrastus [the second head of the Lyceum], at that time not yet well known to the

public. But it is said that after the library was carried to Rome, Tyrannio the

grammarian arranged most of the works in it, and that Andronicus the Rhodian was

furnished by him with copies of them, and published them, and drew up the lists now

current. The older Peripatetics were evidently of themselves accomplished and learned men,

but they seem to have had neither a large nor an exact acquaintance with the writings of

Aristotle and Theophrastus, because the estate of Neleus of Scepsis, to whom Theophrastus

bequeathed his books, came into the hands of careless and illiterate people"

(Plutarch, Life of Sulla 26.1).

The books from Aristotle's library eventually showed up in Rome

after Sulla sacked Athens in 86 BCE. There they came into the

hands of Andronicus (first century BCE) of Rhodes. He organized them and became

the eleventh successor to Aristotle as head of the Lyceum.

The organization of the books in the Aristotelian corpus as we now have is the one Andronicus imposed on Aristotle's writings. This arrangment is systematic. The logical works come first in the corpus. They are followed by the physical works. The ethical works are last.

Aristotle's works are not dialogues. Nor do the works have a traditional chronological ordering.

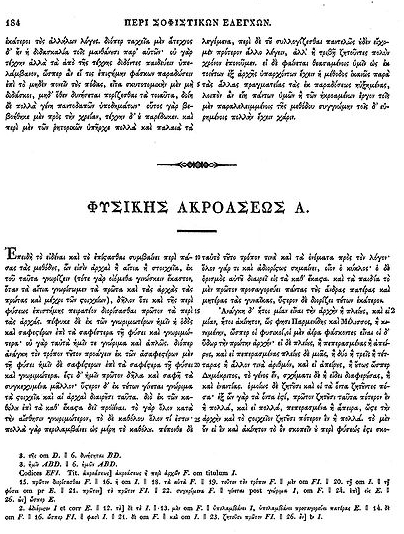

Aristotelis Opera, Immanuel Bekker.

First page of Aristotle's

Physics. In the Bekker numbering, this work begins page 184, line 10 of

the "a" column.

The Oxford Classical Texts library has modern

editions of Aristotle's works.

They include Bekker

numbers that refer to the edition Immanuel Bekker produced in the

19th century CE.

The Oxford Classical Texts library has modern

editions of Aristotle's works.

They include Bekker

numbers that refer to the edition Immanuel Bekker produced in the

19th century CE.

Translations into English

Translations are more of a problem for Aristotle then they are for Plato.

The Perseus Digital Library has some of the works in the Aristotelian corpus.

The Loeb Classical Library (available through the library at ASU with an ASURITE ID) has all the major works in translation with facing Greek texts (but without links to a dictionary).

The standard collection of English translations is The Complete Works of Aristotle volume 1 and 2, edited by Jonathan Barnes (available through the library at ASU with an ASURITE ID).

The best translations are in the Oxford Clarendon Aristotle Series.

Textual Evidence for Aristotle

Aristotle's works are difficult to understand, and it is not at all feasible to read them in their entirety with any care in the short time allotted in a semester class.

We mainly look at parts of these works to get an impression of what Aristotle thought.

• Categories

The Categories is the first work in in the logical

works.

It is a discussion of terms.

• Prior Analytics

The Prior Analytics is in the logical works.

It is a discussion of

deduction.

• Posterior Analytics

The Posterior Analytics is in the logical works.

It is a discussion

of demonstration.

• Physics

The Physics is the first work of the physical works.

It is

a discussion of the existence of natural bodies as forms in matter.

• On the Soul

On the Soul is in the physical works.

It is a discussion of the soul as the form of the

living natural body.

• Metaphysics

The Metaphysics sits between the physical works and the

ethical works.

• Nicomachean Ethics

The Nicomachean Ethics is the first of the ethical works.

It is a

discussion of the good life for a human being.

Sets of Selected Texts

The selection of texts that follow are organized by topic. Read the lectures first.

• Deduction, Demonstration, and Knowledge

Aristotle's theory of the syllogism is a theory of logical deduction. Aristotle thinks that some deductions are demonstrations and that someone who grasps a demonstration has knowledge.

• Induction, Experience, Reason

Aristotle thinks that reason is not inborn but develops naturally in human beings as they become adults. The process in which it develops is induction. This is a causal process that involves perception, memory, and experience.

• The Existence of Natural Bodies

Aristotle thinks that natural bodies have a "nature" (φύσις) and that this nature is a form. He thinks that these forms exist "in matter" and are only "separate in account."

In the central books of the Metaphysics, Aristotle thinks about the "being" of substances.

• The Good Life for a Human Being

Aristotle thinks about the good life for a human being.